Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Group Psychotherapy

Group Psychotherapy: Group Development

Group

Development and Group Dynamics

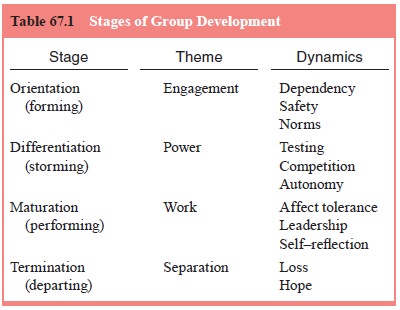

The basic

science informing group treatment is group develop-ment and dynamics.

Understanding of these concepts provides a foundation for the therapist’s

integration of individual, interper-sonal and intrapsychic dynamics with those

of group member-ship (Table 67.1).

Group

Development

The seminal work of Bennis and Shepard (1956) produced a spate of studies demonstrating that groups have a natural developmen-tal sequence. Groups must accomplish certain tasks as they move from a collection of individuals to a functioning and working or-ganization. In this discussion, the focus is on developmental se-quences in groups conducted along psychodynamic principles

Initial (Engagement, Orientation) Phase

Individuals

entering a psychotherapy group are faced with two ma-jor tasks: they have to

decide how they will use the treatment to accomplish their goals and

simultaneously they have to determine the limits of emotional safety. Members

turn to the therapist in hope of gaining information on how to proceed. They

anticipate that the leader, a person they already know and who fulfills a

traditional role, will provide guidance and smooth the way in getting to know

the strangers in the room. In the main, these “dependency” strivings are

frustrated. Members tentatively reveal themselves to others. Gradu-ally,

unwritten and primarily unconscious rules (norms) develop, which help contain

anxiety and set standards for acceptable behav-ior. Therapists help shape behavior

by providing information on how to proceed and by clarifying (interpreting)

underlying anxieties. Common themes and concerns may be highlighted, which

serve to diminish members’ sense of isolation and enhance cohesion.

Reactive (Power, Differentiation) Phase

Many

groups move into this phase by rebelliously rejecting their leader. This may be

followed by a relatively short-lived sense of well-being and harmony. However,

norms are often experienced as restrictive and members may begin to feel as

though they are controlled by the group (group tyranny). In response, they

assert individuality and demonstrate their own power. Struggles be-tween

members emerge, and angry exchanges are not uncommon. Usual norms against

expression of intense intragroup affects are tested and modified in accordance

with members’ personal ca-pacities. Some members may threaten to quit, or they

remain si-lent during this phase as they grapple with their ability to tolerate

conflict. The therapist assists in helping members understand and tolerate

responses to intense feelings and differences.

Mature (Working) Phase

In this

phase, groups have developed considerable cohesion. Members can tolerate

differences and they can contain anxi-ety and allow conflicts to emerge without

having to interrupt exchanges. They have learned to provide and receive

feedback from others without undue defensiveness. A considerable por-tion of

the group transactions is focused on the here and now, and exchanges are

appreciated as containing both reactions to the present and vestiges from prior

relationships (transferences). Members attempt to understand one another at

both surface and in-depth levels. The therapist no longer is the sole expert,

and members are valued for their emotional and cognitive unique-ness.

Therapists continue to help patients understand their in-group reactions and

assist in broadening their perspectives to include the sources (genetic) of

their feelings and their manifesta-tions in their outside world.

Termination Phase

Ending

treatment is the final stage. It is filled with mixed feelings: those of

success and looking to the future and those surrounding separations (Schermer

and Klein, 1996). Often there is a regres-sion as anxieties over departing are

addressed. This provides an additional opportunity to explore the problems that

emerge. Members respond with pleasure at seeing someone “graduate”, but they

also experience loss of a valued contributor to the work and envy over a

colleague’s achievement. A successful termina-tion also offers hope for those

who remain. The therapist monitors the dynamic forces and enables members to

say their farewells within a context of therapeutic accomplishments and

continuing psychological work. In the process, remaining members experi-ence

and integrate their responses to the departure.

Summary

Groups do

not uniformly traverse these developmental phases, and they undergo shifts to

earlier stages under stress, such as vacations or change in membership. A

considerable amount of therapeutic work takes place at each developmental

level. For in-stance, a group of individuals experiencing problems with basic

trust may spend a good deal of time in an initial stage, where these feelings

may be explored. Patients who need to address competitive feelings may

alternate between the reactive and the working phases. Understanding group

development provides a framework for therapists to appreciate the forces that

have an im-pact on members’ feelings and behavior.

Related Topics