Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Group Psychotherapy

Group Psychotherapy: Beginning a Group

Beginning

a Group

Group Organization

Forming a

psychotherapy group is a complex task and attention to organizational details

will anticipate some of the potential haz-ards and smooth the path.

Composition, size, fees, place, duration and time of meetings are elements that

require decisions in ad-vance of recruiting and preparing potential members.

The size

of dynamically-oriented groups ranges from six to 10 members. Groups at the

upper size range generally meet for lengthier periods to provide sufficient

“airtime” for each person. Smaller groups (four members or less) may be

threatened by fears of dissolution (Fulkerson et al., 1981). The duration of meetings is set for 75 to 120

minutes, the norm being 90 minutes. Most groups meet once weekly. Attention

must be paid to the group space. An optimal room will comfortably seat eight to

10 persons with unobstructed views of one another. Seats do not have to be

identical. Both the position and the type of seat members choose may assume

considerable emotional significance. Access to the room needs consideration. Is

there time for members to gather in the group room before the meeting, or is a

waiting room necessary? In private settings, meetings are occasionally held in

a waiting room and therapists must ensure that others do not intrude on that

space.

Careful

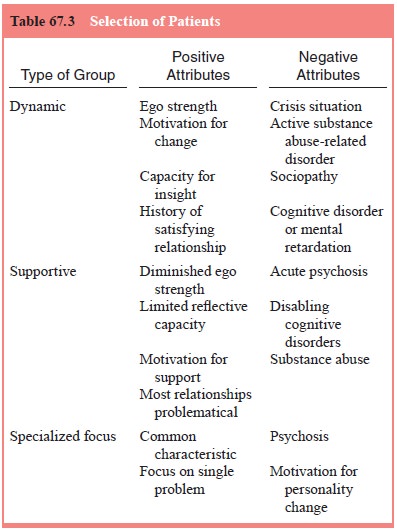

thought must be given to optimal group composi-tion (Table 67.3). Patients

chosen for groups that will explore in-trapsychic elements should have a

capacity for self-reflection and empathy with others. If possible, members with

different person-ality styles should be selected to provide a spectrum of

interac-tive patterns. Other long-term groups may be established with

supportive goals and include patients with significant ego deficits. (Groups

for the chronically mentally ill are discussed separately later.) Groups

designed with a specialized format (e.g., women survivors of sexual abuse, male

perpetrators, or individuals with eating disorders) generally are more focused

on a symptom or a specific behavior and in such cases balanced membership is of

lesser importance.

Recruiting, Selecting and Preparing Patients

Few

applicants requesting psychotherapy consider group treatment. Thus, gathering

six to 10 individuals together may not be a simple task. Patients are more

likely to agree to enter a group if the rationale is explained to them in some

detail. Thus, the therapist needs to be clear about the relationship between

group goals and patient goals (to be discussed below). The therapist also needs

to be familiar with the patient’s history, coping style, symptoms and

personality configurations. In obtaining a patient’s developmental history, the

therapist can specifically search for the person’s interaction in group

settings, such as school, church, recreation and family. Discussion of the

person’s typical reactions to group situations helps engage the patient in

examining his or her roles in interpersonal situations. The screening and

preparatory interviews have five major tasks (Rutan and Stone, 2001):

·

Establish a preliminary alliance between patient

and therapist.

·

Define the patients’ therapeutic goals.

·

Provide information about the nature of group

treatment.

·

Explore the patients’ anticipatory anxiety.

·

Discuss the group agreement and gain the patient’s

acceptance.

Careful

screening helps patients anticipate the tasks of en-tering a group. Such

preparation will decrease, but not eliminate premature termination which may

range from 20 to 50% of mem-bers in newly formed groups.

The Group Agreement

The

agreement represents the framework in which treatment will proceed. It promotes

a structure that defines boundaries between

the group

and the environment, among the members and with the therapist. Although members

accept the agreement, they also break it. Such disruptions are valuable windows

into understand-ing a person’s inner world. The therapist must distinguish

be-tween acts that are disruptive to the group and those that carry more benign

communications (Nitsun, 1996).

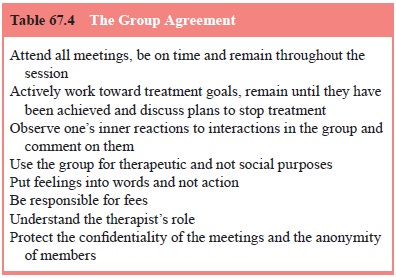

Rutan and

Stone (2001) list the elements of the agreement as shown in Table 67.4.

The

initial element in the agreement addresses patients’ ability to attend all

sessions. Those who have responsibilities that interfere with attendance should

not be admitted into the group (e.g., executives whose conflicts make them

unavailable once every third or fourth week). Similarly, persons who have time

conflicts and would consistently come late or leave early should delay entry

until their schedule can be adapted to that of the group.

In

establishing goals, the patient and therapist enter into a conscious agreement

to work toward specified change. However, unconscious elements contributing to

a patient’s behaviors are likely to emerge in the therapeutic process that may

point to ad-ditional goals worthy of pursuit. Instructions regarding

termina-tion are an additional part of this agreement element. Patients generally

have little idea how to stop treatment, and leaders can indicate that

sufficient time to take leave of the group is an im-portant part of the

therapy. Plans to leave should be discussed and then a date for departure

established that allows sufficient time to say goodbye.

The

succeeding three elements in the agreement address patient behaviors within the

group. Patients slowly learn that one of the major benefits of therapy follows

from addressing feelings and reactions to one another and to the therapist.

Consistent at-tainment of this goal suggests that the group is functioning at a

mature level. Physical contact and verbal abuse are prohibited. Patients unable

to contain these behaviors may be asked to leave the session temporarily.

Although physical touching or hugging may seem soothing and reassuring to some

individuals, for oth-ers it is a threat to their personal boundaries. Those

behaviors are open to analysis.

Therapist’s Role

The group

leader assumes a major, but not the sole, responsibil-ity for the treatment.

The therapist’s special role is established in part by the agreement. Within

that framework, clinicians begin to shape the group to provide participants a

way of using their experience to learn about themselves. Assuming that

patients’

optimal

learning begins with a focus on transactions within the group,

psychodynamically-oriented therapists try to find ways of helping members

examine resistances and defenses against such engagement. In contrast,

clinicians using a more strictly interper-sonal (Yalom, 1995) or a

system-centered orientation (Agazarian, 1997) may actively instruct members to

address one another directly in the here and now of the meeting. The goals of

the different approaches are similar: to use the intragroup processes to

promote personal change. Therapists always benefit from ex-amining their own

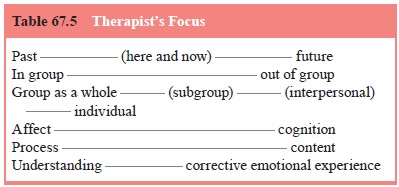

contributions to the construction of the group dialogue. The therapist’s focus,

however, is not exclusively on in-group processes. Rutan and Stone (2001) list

six foci for the therapist’s attention (Table 67.5):

The major

but not exclusive focus promoting change is members learning from the here and

now of treatment. Groups develop a rhythm in which members might address

outside events as a warm-up to exploring in-group interactions, or they might

focus on current feelings and then expand on those experiences in respect to

their outside lives, now, in the past, or in the future. Integration of a

person’s experiences across an extended period enhances feelings of continuity

and stability of the self.

The

therapist monitors the ebb and flow of affects which reflect the group

developmental stage. Members’ capacity to tol-erate intense feelings is

enhanced as trust and cohesion increase. The dialectical tension between affect

and cognition is seen in members’ roles as they attempt to contain dysphoric

states and sustain emotional contacts with one another. Patients may find ways

of managing intense feelings through scapegoating or ex-ternalizing. These are

group-wide processes and should be ad-dressed as such. Some individuals require

cognitive understand-ing before risking immersion into feelings, whereas others

search for affective connections before integrating their experience

cognitively.

The

therapeutic process is fueled by members’ searching for new solutions to their

developmental arrests and conflicts. In general, members communicate feelings

about their in-group ex-perience through associations (not always conscious) to

events in their outside world. As such, the associations can be understood as

metaphoric communication that informs the treatment proc-ess. After a

successful interpretation or clarification, associations to external or

historical events may represent integration of those experiences into members’

psychic structure.

Considerable

individual change takes place via the group relationship without overt

cognitive integration. The sense of sharing, of being understood, of having

needs met, of being responded to in an empathic (corrective) manner may stabilize

a shaky psychic structure and, some patients, to their therapist’s surprise,

may successfully terminate treatment without having achieved understanding

(Stone, 1985). These are the powerful forces for change, labeled “corrective

emotional” experiences. Patients also strive for cognitive integration of their

thoughts andfeelings and, through experiencing and then understanding the

here-and-now, external and developmental incidents, they con-solidate their

learning. Patients are then more prepared to trans-fer their learning from

therapy to situations in their outside world (Ezriel, 1973).

Members’

level of self and ego development influence the course of the group as a

therapeutic agent. Persons suffering from archaic conflicts of trust or psychic

safety, as expressed in a vari-ety of personality disorders (the difficult

patient), may require an extended period of therapy exploring these issues.

Transferences to the group, leader, or peers emerge that reflect these

develop-mental levels.

Related Topics