Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Health Assessment

The Health History - Assessment

The Health History

Throughout assessment,

and particularly when obtaining the his-tory, attention is focused on the

impact of psychosocial, ethnic, and cultural background on the person’s health,

illness, and health-promotion behaviors. The interpersonal and physical

en-vironments, as well as the person’s lifestyle and activities of daily

living, are explored in depth. Many nurses are responsible for ob-taining a

detailed history of the person’s current health problems, past medical history,

family history, and a review of the person’s functional status. This results in

a total health profile that focuses on health as well as illness and is more

appropriately called a health history rather than a medical or a nursing

history.

The format of the health

history traditionally combines the medical history and the nursing assessment,

although formats based on nursing frameworks, such as functional health

patterns, have also become a standard. Both the review of systems and pa-tient

profile are expanded to include individual and family rela-tionships, lifestyle

patterns, health practices, and coping strategies. These components of the

health history are the basis of nursing as-sessment and can be easily adapted

to address the needs of any pa-tient population in any setting, institution, or

agency.

Combining the

information obtained by the physician and the nurse in one health history

prevents duplication of informa-tion and minimizes efforts on the part of the

person to providethis information. This also encourages collaboration among

members of the health care team who share in the collection and interpretation

of the data (Butler, 1999).

THE INFORMANT

The informant, or the

person providing the health history, may not always be the patient, as in the

case of a developmentally de-layed, mentally impaired, disoriented, confused,

unconscious, or comatose patient. The interviewer assesses the reliability of

the informant and the usefulness of the information provided. For example, a

disoriented patient is often unable to provide a reli-able database; people who

abuse drugs and alcohol often deny using these substances. The interviewer must

make a judgment about the reliability of the information (based on the context

of the entire interview), and he or she includes this evaluation in the record.

CULTURAL CONSIDERATIONS

When obtaining the

health history, the interviewer takes into ac-count the person’s cultural

background (Weber & Kelley, 2003). Cultural attitudes and beliefs about

health, illness, health care, hospitalization, the use of medications, and the

use of comple-mentary therapies are derived from each person’s experiences.

They vary according to the person’s ethnic and cultural back-ground. A person

from another culture may have a different view of personal health practices

than the health care practitioner.

Similarly, people from

some ethnic and cultural backgrounds will not complain of pain, even when it is

severe, because outward expressions of pain are considered unacceptable. In

some in-stances they may refuse to take analgesics. Other cultures have their

own folklore and beliefs about the treatment of illnesses. All such differences

in outlook must be taken into account and ac-cepted when caring for members of

other cultures. Attitudes and beliefs about family relationships and the role

of women and el-derly members of a family must be respected even if those

atti-tudes and beliefs conflict with those of the interviewer.

CONTENT OF THE HEALTH HISTORY

When the patient is seen

for the first time by a member of the health care team, the first requirement

is a database (except in emergency situations). The sequence and format of

obtaining data about the patient vary, but the content, regardless of format,

usually addresses the same general topics. A traditional approach includes the

following:

• Biographical data

• Chief complaint

• Present health concern (or present illness)

• Past history

• Family history

• Review of systems

• Patient profile

Biographical Data

Biographical information

puts the patient’s health history in con-text. This information includes the

person’s name, address, age, gender, marital status, occupation, and ethnic

origins. Some in-terviewers prefer to ask more personal questions at this part

of the interview, while others wait until more trust and confidence have been

established or until the patient’s immediate or urgent needs are first

addressed. The patient in severe pain or with another ur-gent problem is

unlikely to have a great deal of patience for an in-terviewer who is more

concerned about marital or occupational status than with quickly addressing the

problem at hand.

Chief Complaint

The chief complaint is

the issue that brings the person to the at-tention of the health care provider.

Questions such as, “Why have you come to the health center today?” or “Why were

you admit-ted to the hospital?” usually elicit the chief complaint. In the home

setting, the initial question might be, “What is bothering you most today?”

When a problem is identified, the person’s exact words are usually recorded in

quotation marks (Orient, 2000). However, a statement such as, “My doctor sent

me” should be followed up with a question that identifies the probable reason

why the person is seeking health care; this reason is then identified as the

chief complaint.

Present Health Concern or Illness

The history of the

present health concern or illness is the single most important factor in

helping the health care team to arrive at a diagnosis or determine the person’s

needs. The physical exami-nation is helpful but often only validates the

information obtained from the history. A careful history assists in correct

selection of ap-propriate diagnostic tests. While diagnostic test results can

be helpful, they often support rather than establish the diagnosis.

If the present illness

is only one episode in a series of episodes, the entire sequence of events is

recorded. For example, a history from a patient whose chief complaint is an

episode of insulin shock describes the entire course of the diabetes to put the

cur-rent episode in context. The details of the health concern or pres-ent

illness are described from onset until the time of contact with the health care

team. These facts are recorded in chronological order, beginning with, for

example, “The patient was in good health until . . .” or “The patient first

experienced abdominal pain 2 months prior to seeking help.”

The history of the

present illness or problem includes such in-formation as the date and manner

(sudden or gradual) in which the problem occurred, the setting in which the

problem occurred (at home, at work, after an argument, after exercise),

manifesta-tions of the problem, and the course of the illness or problem. This

includes self-treatment (including complementary therapies), medical

interventions, progress and effects of treatment, and the patient’s perceptions

of the cause or meaning of the problem.

Specific symptoms (pain,

headache, fever, change in bowel habits) are described in detail, along with

the location and radia-tion (if pain), quality, severity, and duration. The

interviewer also asks if the problem is persistent or intermittent, what

factors ag-gravate or alleviate it, and if any associated manifestations exist.

Associated

manifestations are symptoms that occur simultane-ously with the chief

complaint. The presence or absence of such symptoms may shed light on the

origin or extent of the problem, as well as on the diagnosis. These symptoms

are referred to as sig-nificant positive or negative findings and are obtained

from a re-view of systems directly related to the chief complaint. For example,

if the person reports a vague symptom such as fatigue or weight loss, all body

systems are reviewed and included in this sec-tion of the history. If, on the

other hand, the person’s chief com-plaint is chest pain, only the

cardiopulmonary and gastrointestinal systems may be included in the history of

the present illness. In either situation, both positive and negative findings

are recorded to define the problem further.

Past Health History

A detailed summary of

the person’s past health is an important part of the database. After

determining the general health status, the interviewer may inquire about

immunization status and any known allergies to medications or other substances.

The dates of immunization are recorded, along with the type of allergy and

ad-verse reactions. The person is asked to provide information, if known, about

his or her last physical examination, chest x-ray, electrocardiogram, eye

examination, hearing tests, dental checkup, as well as Papanicolaou (Pap) smear

and mammogram (if female), digital rectal examination of the prostate gland (if

male), and any other pertinent tests. Previous illnesses are then discussed.

Nega-tive as well as positive responses to a list of specific diseases are

recorded. Dates, or the age of the patient at the time of illness, as well as

the names of the primary health care provider and hospi-tal, the diagnosis, and

the treatment are also recorded. A history of the following areas is elicited:

·

Childhood illness—rubeola, rubella, polio, whooping

cough, mumps, chickenpox, scarlet fever, rheumatic fever, strep throat

·

Adult illnesses

·

Psychiatric illnesses

·

Injuries—burns, fractures, head injuries

·

Hospitalizations

·

Surgical and diagnostic procedures

·

Current medications—prescription, over-the-counter,

home remedies, complementary therapies

·

Use of alcohol and other drugs

If a particular

hospitalization or major medical intervention is related to the present

illness, the account of it is not repeated; rather, the report refers to the

appropriate part of the report, such as “see history of present illness” or

“see HPI” on the data sheet.

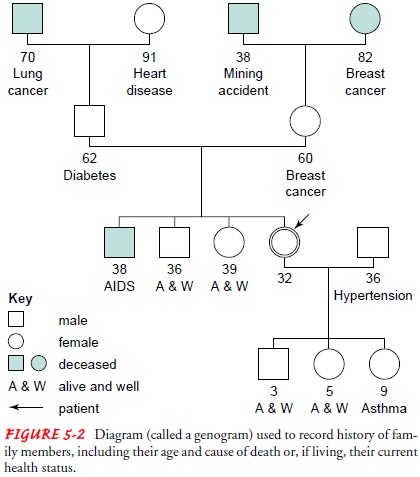

Family History

The age and health

status, or the age and cause of death, of first-order relatives (parents,

siblings, spouse, children) and second-order relatives (grandparents, cousins)

are elicited to identify diseases that may be genetic in origin, communicable,

or possi-bly environmental in cause. The following diseases are generally

included: cancer, hypertension, heart disease, diabetes, epilepsy, mental

illness, tuberculosis, kidney disease, arthritis, allergies, asthma,

alcoholism, and obesity. One of the easiest methods of recording such data is

by using the family tree or genogram (Fig. 5-2). The results of genetic testing

or screening, if known, are recorded.

Review of Systems

The systems review

includes an overview of general health as well as symptoms related to each body

system. Questions are asked about each of the major body systems in terms of

past or present symptoms. Reviewing each body system helps reveal any relevant

data. Negative as well as positive answers are recorded. If the pa-tient

responds positively to questions about a particular system, the information is

analyzed carefully. If any illnesses were previ-ously mentioned or recorded, it

is not necessary to repeat them in this part of the history. Instead, reference

is made to the appro-priate place in the history where the information can be

found.

A review of systems can be organized in a formal checklist, which becomes a part of the health history. One advantage of a checklist is that it can be easily audited and is less subject to error than a system that relies heavily on the interviewer’s memory.

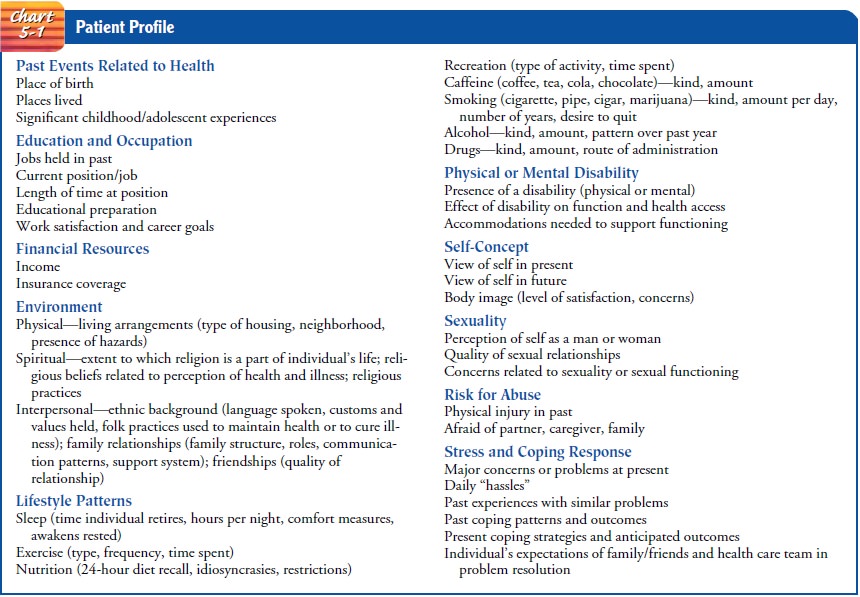

Patient Profile

In the patient profile,

more biographical information is gathered. A complete composite, or profile, of

the patient is critical to an analysis of the chief complaint and of the

person’s ability to deal with the problem. A complete patient profile is

summarized in Chart 5-1.

The information elicited

at this point in the interview is highly personal and subjective. During this

stage, the person is encour-aged to express feelings honestly and to discuss

personal experi-ences. It is best to begin with general, open-ended questions

and to move to direct questioning when specific facts are needed. The patient is

often less anxious when the interview progresses from information that is less

personal (birthplace, occupation, educa-tion) to information that is more

personal (sexuality, body image, coping abilities).

A general patient

profile consists of the following content areas:

• Past life events related to health

• Education and occupation

• Environment (physical, spiritual, cultural, interpersonal)

• Lifestyle (patterns and habits)

• Presence of a physical or mental disability

• Self-concept

• Sexuality

• Risk for abuse

• Stress and coping response

PAST LIFE EVENTS RELATED TO HEALTH

The patient profile begins with a brief life history. Questions about place of birth and past places of residence help focus at-tention on the earlier years of life. Personal experiences during childhood or adolescence that have special significance may be elicited by asking, “Was there anything that you experienced as a child or adolescent that would be helpful for me to know about?”

The interviewer’s intent

is to encourage the person to make a quick review of his or her earlier life,

highlighting information of particular significance. Although many patients may

not recall anything significant, others may share information such as a per-sonal

achievement, a failure, a developmental crisis, or an in-stance of physical or

emotional abuse.

EDUCATION AND OCCUPATION

Inquiring about current

occupation can reveal much about a per-son’s economic status and educational

preparation. A statement such as, “Tell me about your job” often elicits

information about role, job tasks, and satisfaction with the position. Direct

questions about past employment and career goals may be asked if the per-son

does not provide this information.

Asking the person what

kind of educational requirements were necessary to attain his or her present

job is a more sensitive approach to educational background than asking whether

he or she graduated from high school. Information about the patient’s general

financial status may be obtained by questions such as, “Do you have any

financial concerns at this time?” or “Sometimes there just doesn’t seem to be

enough money to make ends meet. Are you finding this true?” Inquiry about the

person’s insurance coverage and plans for health care payment is also

appropriate.

ENVIRONMENT

The person’s physical environment and its potential hazards, spir-itual awareness, cultural background, interpersonal relationships, and support system are included in the concept of environment.

Physical Environment

Information is elicited

about the type of housing (apartment, du-plex, single-family) in which the

person lives, its location, the level of safety and comfort within the home and

neighborhood, and the presence of environmental hazards (eg, isolation,

poten-tial fire risks, inadequate sanitation). The patient’s environment takes

on special importance if the patient is homeless or living in a homeless

shelter or has a disability.

Spiritual Environment

The term “spiritual

environment” refers to the degree to which a person thinks about or

contemplates his or her existence, accepts challenges in life, and seeks and

finds answers to personal ques-tions. Spirituality may be expressed through

identification with a particular religion. Spiritual values and beliefs often

direct a per-son’s behavior and approach to health problems and can influ-ence

responses to sickness. Illness may create a spiritual crisis and can place

considerable stress on a person’s internal resources and beliefs. Inquiring

about spirituality can identify possible support systems as well as beliefs and

customs that need to be considered in planning care. Thus, information is

gathered in the following three areas:

·

The extent to which religion is a part of the

person’s life

·

Religious beliefs related to the person’s

perception of health and illness

·

Religious practices

The following questions

can be used in a spiritual assessment:

· Is religion or God

important to you?

· If yes, in what way?

· If no, what is the most

important thing in your life?

· Are there any religious

practices that are important to you?

· Do you have any

spiritual concerns because of your present health problem?

Interpersonal and Cultural Environment

Cultural influences,

relationships with family and friends, and the presence or absence of a support

system are all a part of one’s in-terpersonal environment. The beliefs and

practices that have been shared from generation to generation are known as

cultural or ethnic patterns. They are expressed through language, dress,

di-etary choices, and role behaviors, in perceptions of health and ill-ness,

and in health-related behaviors. The influence of these beliefs and customs on

how a person reacts to health problems and interacts with health care providers

cannot be underestimated (Fuller & Schaller-Ayers, 2000). For this reason,

the health history includes information about ethnic identity (cultural and

social) and racial identity (biologic). The following questions may assist in

obtaining relevant information:

· Where did your parents

or ancestors come from? When?

· What language do you

speak at home?

· Are there certain

customs or values that are important to you?

· Is there anything

special you do to keep in good health?

· Do you have any specific

practices for treating illness?

Family Relationships and Support System

An assessment of family

structure (members, ages, roles), patterns of communication, and the presence

or absence of a support sys-tem is an integral part of the patient profile. Although

the tradi-tional family is recognized as a mother, a father, and children, many

different types of living arrangements exist within our so-ciety. “Family” may

mean two or more people bound by emo-tional ties or commitments. Live-in

companions, roommates, and close friends can all play a significant role in an

individual’s support system.

LIFESTYLE

The lifestyle section of

the patient profile provides information about health-related behaviors. These

behaviors include patterns of sleep, exercise, nutrition, and recreation, as

well as personal habits such as smoking and the use of drugs, alcohol, and

caffeine. Although most people readily describe their exercise patterns or

recreational activities, many are unwilling to report their smok-ing, alcohol use,

and drug use; many deny or understate the de-gree to which they use such

substances. Questions such as, “What kind of alcohol do you enjoy drinking at a

party?” may elicit more accurate information than, “Do you drink?” The specific

type of alcohol (eg, wine, liquor, beer) and the amount ingested per day or per

week (eg, 1 pint of whiskey daily for 2 years) are described.

When alcohol abuse is

suspected, additional information may be obtained by using common alcohol

screening questionnaires such as the CAGE (Cutting down, Annoyance by

criticism, Guilty feelings, and Eye-openers), AUDIT (Alcohol Use Disorders

Identification Test), TWEAK (Tolerance, Worry, Eye-opener, Amnesia, Kut down),

or SMAST (Short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test). Chart 5-2 shows the CAGE

Questions Adapted to Include Drugs (CAGEAID).

Similar questions can be

used to elicit information about smoking and caffeine consumption. Questions

about drug use follow naturally after questions about smoking, caffeine

con-sumption, and alcohol use. A nonjudgmental approach will make it easier for

the person to respond truthfully and factually. If street names or unfamiliar

terms are used to describe drugs, the person is asked to define the terms used.

Investigation of

lifestyle should also include questions about complementary and alternative

therapies. It is estimated that as many as 40% of Americans use some type of

complementary or al-ternative therapies, including special diets, the use of

prayer, visu-alization, or guided imagery, massage, meditation, herbal

products, and many others (Evans, 2000; King, Pettigrew & Reed, 1999; Kuhn,

1999). Marijuana is used for symptom management, espe-cially pain, in a number

of chronic conditions (Mathre, 2001).

PHYSICAL OR MENTAL DISABILITY

The general patient

profile also needs to contain questions about any hearing, vision, cognitive,

or physical disability. The presence of an obvious physical deformity—for

instance, if the patient walks with crutches or needs a wheelchair to get

around—needs further investigation. The etiology of the disability should be

elicited; the length of time the patient has had the disability and the impact

on function and health access are important to assess.

SELF-CONCEPT

Self-concept refers to

one’s view of oneself, an image that has de-veloped over many years. To assess

self-concept, the interviewer might ask the person how he or she views life:

“How do you feel about your life in general?” A person’s self-concept can be

threat-ened very easily by changes in physical function or appearance or other

threats to health. The impact of certain medical conditions or surgical

interventions, such as a colostomy or a mastectomy, can threaten body image.

Asking, “Do you have any particular concerns about your body?” may elicit useful

information about self-image.

SEXUALITY

No area of assessment is

more personal than the sexual history. Interviewers are frequently

uncomfortable with such questions and ignore this area of the patient profile

or conduct a very cur-sory interview at this point. Lack of knowledge about

sexuality and anxiety about one’s own sexuality may hamper the inter-viewer’s

effectiveness in dealing with this subject (Ross, Channon-Little & Rosser,

2000).

Sexual assessment can be

approached at the end of the inter-view, at the time interpersonal or lifestyle

factors are assessed, or it can be a part of the genitourinary history within

the review of systems. For instance, it may be easier to approach a discussion

of sexuality after a discussion of menstruation. A similar discus-sion with the

male patient would follow questions related to the urinary system.

Obtaining the sexual

history provides an opportunity to dis-cuss sexual matters openly and gives the

person permission to express sexual concerns to an informed professional. The

inter-viewer must be nonjudgmental and must use language appropri-ate to the

patient’s age and background. It is advisable to begin the assessment with a

general question concerning the person’s developmental stage and the presence

or absence of intimate re-lationships. Such questions may lead to a discussion

of concerns related to sexual expression or the quality of a relationship, or

to questions about contraception, risky sexual behaviors, and safer sex

practices.

Finding out whether a person

is sexually active should precede any attempts to explore issues related to

sexuality and sexual func-tion. Care should be taken to initiate conversations

about sexuality with elderly patients and not to treat them as asexual beings

(Miller, Zylstra & Stranridge, 2000). Questions are worded in such a way

that the person feels free to discuss his or her sexual-ity regardless of

marital status or sexual preference. Direct ques-tions are usually less

threatening when prefaced with such statements as, “Most people feel that . .

.” or “Many people worry about. . . .” This suggests the normalcy of such

feelings or be-havior and encourages the person to share information that might

otherwise be omitted from fear of seeming “different.”

If the person answers abruptly

or does not wish to carry the dis-cussion any further, then the interviewer

should move to the next topic. However, introducing the subject of sexuality

indicates to the person that a discussion of sexual concerns is acceptable and

can be approached again in the future if so desired.

RISK FOR ABUSE

A topic of growing

importance in today’s society is physical, sex-ual, and psychological abuse.

Such abuse occurs at all ages, to men and women from all socioeconomic, ethnic,

and cultural groups (Little, 2000; Marshall, Benton & Brazier, 2000). Few

patients, however, will discuss this topic unless they are asked specifically

about it. Therefore, it is important to ask direct questions, such as:

· Is anyone physically

hurting you?

· Has anyone ever hurt you

physically or threatened to do so?

· Are you ever afraid of

anyone close to you (your partner, caretaker, or other family members)?

If the person’s response indicates that abuse is a risk, further assessment is called for and efforts are made to ensure the per-son’s safety and provide access to appropriate community and professional resources and support systems.

Further discussion of domestic violence and

abuse. When questioned directly, elderly patients rarely admit to abuse

(Marshall, Benton & Brazier, 2000). Health care professionals should assess

for risk factors, such as high levels of stress or al-coholism in caregivers,

evidence of violence, high emotions as well as financial, emotional, or

physical dependency. Patients who are elderly or disabled are at increased risk

for abuse and should be asked about it as a routine part of assessment.

STRESS AND COPING RESPONSES

Each person handles

stress differently. How well we adapt de-pends on our ability to cope. During a

health history, past cop-ing patterns and perceptions of current stresses and

anticipated outcomes are explored to identify the person’s overall ability to

handle stress. It is especially important to identify expectations that the

person may have of family, friends, and caregivers in pro-viding financial,

emotional, or physical support.

OTHER HEALTH HISTORY FORMATS

The health history

format discussed is only one pos-sible format that is useful in obtaining and

organizing information about a person’s health status. Some consider this

traditional for-mat to be inappropriate for nurses because it does not focus

exclu-sively on the assessment of human responses to actual or potential health

problems. Several attempts have been made to develop an assessment format and

database with this focus in mind. One ex-ample is the nursing database

prototype based on the North Amer-ican Nursing Diagnosis Association’s (NANDA)

Unitary Person Framework and its nine human response patterns: exchanging,

communicating, relating, valuing, choosing, moving, perceiving, knowing, and

feeling. Although there is support in nursing for using this approach, no

consensus for its use has been reached.

The National Center for

Health Services Research of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

and other groups from the public and private sectors have focused on assessing

not only biologic health but also other dimensions of health. These dimen-sions

include physical, functional, emotional, mental, and social health. Modern efforts

to assess health status have focused on the manner in which disease or

disability affects the patient’s functional status—that is, the ability of the

person to function normally and perform his or her usual physical, mental, and

social activities. An emphasis on functional assessment is viewed as more

holistic than the traditional health or medical history. Instruments to assess

health status in these ways may be used by nurses along with their own clinical

assessment skills to determine the impact of illness, dis-ease, disability, and

health problems on functional status.

Health concerns that are

not complex (earache, tonsillectomy) and can be resolved in a short period of

time usually do not require the depth or detail that is required when a person

is experiencing a major illness or health problem. Additional assessments that

go beyond the general patient profile may be used when the patient’s health

problems are acute and complex or when the illness is chronic. Individuals

should be asked about their continuing health promotion and screening

practices. Patients who have not been in-volved in these practices in the past

are educated about their im-portance and are referred to appropriate health

care providers.

Regardless of the

assessment format used, the nurse’s focus during data collection is different

from that of the physician and other health team members; however, it

complements these ap-proaches and encourages collaboration among the health

care providers, as each member brings his or her own expertise and focus to the

situation.

Related Topics