Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Health Assessment

Physical Health Assessment

Physical Assessment

Physical assessment, or

the physical examination, is an integral part of nursing assessment. The basic

techniques and tools used in performing a physical examination. The examination

of specific systems, including spe-cial maneuvers. Because the patient’s

nutritional status is an important factor in health and well-being.

The physical examination

is usually performed after the health history is obtained. It is carried out in

a well-lighted, warm area. The patient is asked to undress and draped

appropriately so that only the area to be examined is exposed. The person’s

physical and psychological comfort is considered at all times. Procedures and

sensations to expect are described to the patient before each part of the

examination. The examiner’s hands are washed before and immediately after the

examination. Fingernails are kept short to avoid injuring the patient. The

examiner wears gloves when there is a possibility of coming into contact with

blood or other body secretions during the physical examination.

An organized and

systematic examination is the key to obtain-ing appropriate data in the

shortest time. Such an approach en-courages cooperation and trust on the part

of the patient. The individual’s health history provides the examiner with a

health pro-file that guides all aspects of the physical examination. Although

the sequence of physical examination depends on the circum-stances and on the

patient’s reason for seeking health care, the complete examination usually

proceeds as follows:

· Skin

· Head and neck

· Thorax and lungs

· Breasts

· Cardiovascular system

· Abdomen

· Rectum

· Genitalia

· Neurologic system

· Musculoskeletal system

In clinical practice,

all relevant body systems are tested through-out the physical examination, not

necessarily in the sequence de-scribed (Weber & Kelley, 2003). For example,

when the face is examined, it is appropriate to check for facial asymmetry and,

thus, for the integrity of the seventh cranial nerve; the examiner does not

need to repeat this as part of a neurologic examination. When sys-tems are

combined in this manner, the patient does not need to change positions

repeatedly, which can be exhausting and time-consuming.

A “complete” physical

examination is not routine. Many of the body systems are selectively assessed

on the basis of the individ-ual’s presenting problem. If, for example, a

healthy 20-year-old college student requires an examination to play basketball

and re-ports no history of neurologic abnormality, the neurologic assess-ment

is brief. Conversely, a history of transient numbness and diplopia (double

vision) usually necessitates a complete neurologic investigation. Similarly, a

person with chest pain receives a much more intensive examination of the chest

and heart than the per-son with an earache. In general, the individual’s health

history guides the examiner in obtaining additional data for a complete picture

of the patient’s health.

The process of learning

physical examination requires repeti-tion and reinforcement in a clinical

setting. Only after basic physical assessment techniques are mastered can the

examiner tailor the routine screening examination to include thorough

assess-ments of a particular system, including special maneuvers.

The basic tools of the

physical examination are vision, hearing, touch, and smell. These human senses

may be augmented by spe-cial tools (eg, stethoscope, ophthalmoscope, and reflex

hammer) that are extensions of the human senses; they are simple tools that

anyone can learn to use well. Expertise comes with practice, and sophistication

comes with the interpretation of what is seen and heard. The four fundamental

techniques used in the physical ex-amination are inspection, palpation,

percussion, and auscultation (Weber & Kelley, 2003).

INSPECTION

The first fundamental

technique is inspection or observation. General inspection begins with the

first contact with the patient. Introducing oneself and shaking hands provide

opportunities for making initial observations: Is the person old or young? How

old? How young? Does the person appear to be his or her stated age? Is the

person thin or obese? Does the person appear anxious or depressed? Is the

person’s body structure normal or abnormal? In what way, and how different from

normal? It is essential to pay attention to the details in observation. Vague,

general statements are not a substitute for specific descriptions based on

careful ob-servation; for example:

· “The person appears

sick.” In what way does he or she ap-pear sick? Is the skin clammy, pale,

jaundiced, or cyanotic; is the person grimacing in pain; is breathing

difficult; does he or she have edema? What specific physical features or

be-havioral manifestations indicate that the person is “sick”?

· “The person appears

chronically ill.” In what way does he or she appear chronically ill? Does the

person appear to have lost weight? People who lose weight secondary to

muscle-wasting diseases (eg, AIDS, malignancy) have a dif-ferent appearance

than those who are merely thin, and weight loss may be accompanied by loss of

muscle mass or atrophy. Does the skin have the appearance of chronic

ill-ness—that is, is it pale, or does it give the appearance of de-hydration or

loss of subcutaneous tissue? These important observations are documented in the

patient’s chart or health record.

Among general

observations that should be noted in the ini-tial examination of the patient

are posture and stature, body movements, nutrition, speech pattern, and vital

signs.

Posture and Stature

The posture that a

person assumes often provides valuable infor-mation about the illness. Patients

who have breathing difficulties (dyspnea) secondary to cardiac disease prefer

to sit and may re-port feeling short of breath lying flat for even a brief

time. People with obstructive pulmonary disease not only sit upright but also

may thrust their arms forward and laterally onto the edge of the bed (tripod

position) to place accessory respiratory muscles at an optimal mechanical

advantage. Those with abdominal pain due to peritonitis prefer to lie perfectly

still; even slight jarring of the bed will cause agonizing pain. In contrast,

patients with abdom-inal pain due to renal or biliary colic are often restless

and may pace the room. Patients with meningeal irritation may experience head

or neck pain on bending the head or flexing their knees

Body Movements

Abnormalities of body

movement may be of two general kinds: generalized disruption of voluntary or

involuntary movement, and asymmetry of movement. The first category includes

tremors of a wide variety; some tremors may occur at rest (Parkinson’s

disease), whereas others occur only on voluntary movement (cerebellar ataxia).

Other tremors may exist during both rest and activity (alcohol withdrawal

syndrome, thyrotoxicosis). Some voluntary or involuntary movements are fine,

others quite coarse. At the extreme are the convulsive movements of epilepsy or

tetanus and the choreiform (involuntary and irregular) movements of patients

with rheumatic fever or Huntington’s disease. Other aspects of body movement

that are noted on inspection include spasticity, muscle spasms, and an abnormal

gait.

Asymmetry of movement,

in which only one side of the body is affected, may occur with disorders of the

central nervous sys-tem (CNS), principally in those patients who have had

cerebro-vascular accidents (strokes). The patient may have drooping of one side

of the face, weakness or paralysis of the extremities on one side of the body,

and a foot-dragging gait. Spasticity (in-creased muscle tone) may also be

present, particularly in patients with multiple sclerosis.

Nutrition

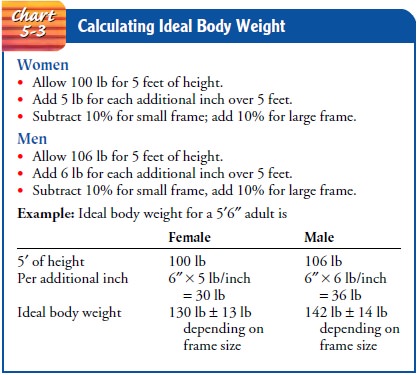

Nutritional status is

important to note. Obesity may be gener-alized as a result of excessive intake

of calories or may be specif-ically localized to the trunk in those with

endocrine disorders (Cushing’s disease) or those who have been taking

cortico-steroids for long periods of time. Loss of weight may be gener-alized

as a result of inadequate caloric intake or may be seen in loss of muscle mass

with disorders that affect protein synthesis.

Speech Pattern

Speech may be slurred

because of CNS disease or because of dam-age to cranial nerves. Recurrent

damage to the laryngeal nerve will produce hoarseness, as will disorders that

produce edema or swelling of the vocal cords. Speech may be halting, slurred,

or in-terrupted in flow in some CNS disorders (eg, multiple sclerosis).

Vital Signs

The recording of vital

signs is a part of every physical examina-tion. Blood pressure, pulse rate,

respiratory rate, and body tem-perature measurements are obtained and recorded.

Acute changes and trends over time are documented; unexpected changes and

values that deviate significantly from the patient’s normal values are brought

to the attention of the patient’s primary health care provider. The “fifth

vital sign,” pain, is also assessed and docu-mented, if indicated.

Fever is an increase in body temperature above normal. A nor-mal oral temperature for most people is an average of 37.0°C (98.6°F); however, some variation is normal. Some people’s tem-peratures are quite normal at 36.6°C (98°F) and others at 37.3°C (99°F). There is a normal diurnal variation of a degree or two in body temperature throughout the day; with temperature usually lowest in the morning and rising during the day to between 37.3° and 37.5°C (99° to 99.5°F), then decreasing again during the night.

PALPATION

Palpation is a vital

part of the physical examination. Many struc-tures of the body, although not

visible, may be assessed through the techniques of light and deep palpation

(Fig. 5-3). Examples include superficial blood vessels, lymph nodes, the

thyroid, the organs of the abdomen and pelvis, and the rectum. When the

ab-domen is examined, auscultation is performed before palpation and percussion

to avoid altering bowel sounds.

Sounds generated within

the body, if within specified fre-quency ranges, also may be detected through

touch. Thus, cer-tain murmurs generated in the heart or within blood vessels

(thrills) may be detected. Thrills cause a sensation to the hand much like the

purring of a cat. Voice sounds are transmitted along the bronchi to the

periphery of the lung. These may be per-ceived by touch and may be altered by

disorders affecting the lungs. The phenomenon is called tactile fremitus and is useful in assessing diseases of the chest.

PERCUSSION

The technique of percussion (Fig. 5-4) translates the application of physical force into sound. It is a skill requiring practice but one that yields much information about disease processes in the chest and abdomen. The principle is to set the chest wall or abdominal wall into vibration by striking it with a firm object. The sound produced reflects the density of the underlying structure. Certain densities produce sounds as percussion notes.

These sounds, listed in a sequence that proceeds

from the least to the most dense, are called tympany, hyperresonance,

resonance, dullness, and flatness. Tym-pany is the drumlike sound produced by

percussing the air-filled stomach. Hyperresonance is audible when one percusses

over in-flated lung tissue in someone with emphysema. Resonance is the sound

elicited over air-filled lungs. Percussion of the liver produces a dull sound,

whereas percussion of the thigh results in flatness.

Percussion allows the

examiner to assess such normal anatomic details as the borders of the heart and

the movement of the di-aphragm during inspiration. One may determine the level

of pleural effusion (fluid in the pleural cavity) and the location of a

consolidated area caused by pneumonia or atelectasis (collapse) of a lobe of

the lung. The use of percussion is described further with disorders of the

thorax and abdomen.

AUSCULTATION

Auscultation is the

skill of listening to sounds produced within the body created by the movement

of air or fluid. Examples in-clude breath sounds, the spoken voice, bowel

sounds, cardiac murmurs, and heart sounds. Physiologic sounds may be normal

(eg, first and second heart sounds) or pathologic (eg, heart mur-murs in

diastole, or crackles in the lung). Some normal sounds may be distorted by

abnormalities of structures through which the sound must travel (eg, changes in

the character of breath sounds as they travel through the consolidated lung of

the patient with lobar pneumonia).

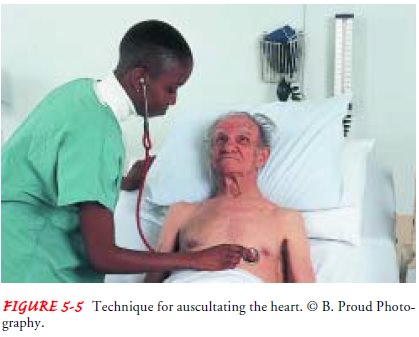

Sound produced within

the body, if of sufficient amplitude, may be detected with the stethoscope,

which functions as an ex-tension of the human ear and channels sound. Two end

pieces are available for the stethoscope: the bell and the diaphragm. The bell

is used to assess very-low-frequency sounds such as diastolic heart murmurs.

The entire surface of the bell’s disc is placed lightly on the skin surface to

avoid flattening the skin and reducing audible vibratory sensations. The

diaphragm, the larger disc, is used to as-sess high-frequency sounds such as

heart and lung sounds and is held in firm contact with the skin surface (Fig.

5-5). Touching the tubing or rubbing other surfaces (hair, clothing) during

ausculta-tion is avoided to minimize extraneous noises.

Sound produced by the body, like any other sound, is charac-terized by intensity, frequency, and quality. Intensity, or loudness, associated with physiologic sound is low; thus, the use of the stethoscope is needed.

Frequency, or pitch, of physiologic

sound is in reality “noise” in that most sounds consist of a frequency spectrum

as opposed to the single-frequency sounds that we as-sociate with music or the

tuning fork. The frequency spectrum may be quite low, yielding a rumbling

noise, or comparatively high, producing a harsh or blowing sound. Quality of sound re-lates to overtones

that allow one to distinguish between different sounds. Sound quality enables

the examiner to distinguish be-tween the musical quality of high-pitched

wheezing and the low-pitched rumbling of a diastolic murmur.

Related Topics