Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Health Assessment

Nutritional Assessment

Nutritional Assessment

An additional area of

concern that is often integrated into the health history and physical

examination is an in-depth nutritional assessment. Nutrition is important to

maintain health and to pre-vent disease and death (Kant, Schatzkin, Graubard

& Schairer, 2000; Landi, Onder, Gambassi et al., 2000; Stampfer, Hu &

Manson, 2000). Disorders caused by nutritional deficiency, over-eating, or

eating poorly balanced meals are among the leading causes of illness and death

in the United States today. The three leading causes of death are related, in

part, to consequences of un-healthy nutrition: heart disease, cancer, and

stroke (Hensrud, 1999). Other examples of health problems associated with poor

nutrition include obesity, osteoporosis, cirrhosis, diverticulitis, and eating

disorders. When illness or injury occurs, optimal nu-trition is an essential

factor in promoting healing and resisting in-fection and other complications

(Braunschweig, Gomez & Sheean, 2000). Assessment of a person’s nutritional

status provides infor-mation on obesity, undernutrition, weight loss,

malnutrition, de-ficiencies in specific nutrients, metabolic abnormalities, the

effects of medications on nutrition, and special problems of the hospi-talized

patient and the person who is cared for in the home and in other community

settings.

Certain signs and

symptoms that suggest possible nutritional deficiency are easy to note because

they are specific. Other phys-ical signs may be subtle and must be carefully

assessed. A physi-cal sign that suggests a nutritional abnormality should be

pursued further. For example, certain signs that may appear to indicate

nutritional deficiency may actually reflect other systemic condi-tions (eg,

endocrine disorders, infectious disease). Others may re-sult from impaired

digestion, absorption, excretion, or storage of nutrients in the body.

The sequence of

assessment of parameters may vary, but eval-uation of nutritional status

includes one or more of the following methods: measurement of body mass index

(BMI) and waist cir-cumference; biochemical measurements (albumin, transferrin,

prealbumin, retinol-binding protein, total lymphocyte count, elec-trolyte

levels, creatinine/height index); clinical examination find-ings; and dietary

data.

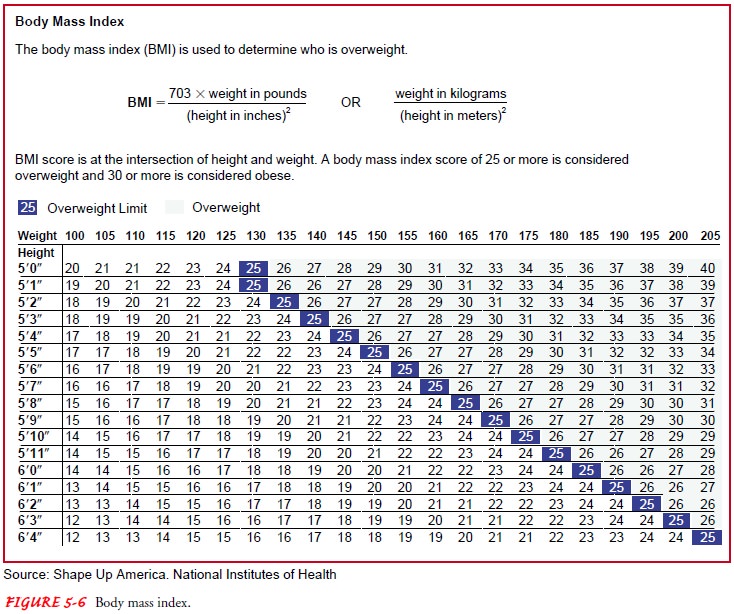

BODY MASS INDEX

BMI is a ratio based on

body weight and height. The obtained value is compared to the established

standards; however, trends or changes in values over time are considered more

useful than isolated or one-time measurements. BMI (Fig. 5-6) is highly

correlated with body fat, but increased lean body mass or a large body frame

can also increase the BMI. Individuals who have a BMI below 24 (or who are 80%

or less of their desirable body weight for height) are at increased risk for

problems associated with poor nutritional status. In addition, a low BMI is

associ-ated with higher mortality rates in hospitalized patients and

community-dwelling elderly (Landi et al., 2000; Landi, Zuccala, Gambassi et

al., 1999).

Those who have a BMI of

25 to 29 are considered overweight; those with a BMI of 30 to 39 are considered

obese; above 40 is considered extreme obesity (National Institutes of Health,

2000).

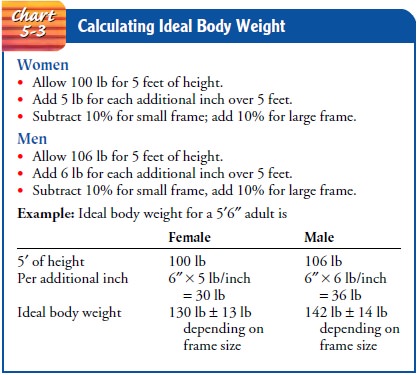

It is important to assess for usual body weight and height. Current weight does not provide information about recent changes in weight; therefore, the patient is asked about his or her usual body weight (Chart 5-3). Decreased height may be due to osteoporosis, an important problem related to nutrition, espe-cially in postmenopausal women. A loss of 2 or 3 inches of height may indicate osteoporosis.

In addition to the calculation of BMI, waist circumference measurement is particularly useful for patients who are catego rized as of normal weight or overweight. To measure waist cir-cumference, a tape measure is placed in a horizontal plane around the abdomen at the level of the iliac crest. Men who have waist circumferences greater than 40 inches and women who have waist circumferences greater than 35 inches have excess abdominal fat. Those with a high waist circumference are at increased risk of di-abetes, dyslipidemias, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease (National Institutes of Health, 2000).

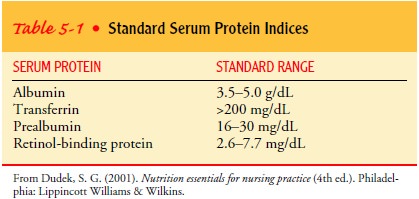

BIOCHEMICAL ASSESSMENT

Biochemical assessment

reflects both the tissue level of a given nu-trient and any abnormality of

metabolism in the utilization of nu-trients. These determinations are made from

studies of serum (serum protein, serum albumin and globulin, transferrin,

retinol-binding protein, hemoglobin, serum vitamin A, carotene, and vi-tamin C)

and studies of urine (creatinine, thiamine, riboflavin, niacin, and iodine).

Some of these tests, while reflecting recent intake of the elements detected,

can also identify below-normal levels when there are no clinical symptoms of

deficiency (see Table 5-1 for a description of serum protein indices).

Low serum albumin and

transferrin levels are often used as mea-sures of protein deficits in adults

and are expressed as percentages of normal values. Albumin synthesis depends on

normal liver func-tion and an adequate supply of amino acids. Because the body

stores a large amount of albumin, the serum albumin level may not decrease

until malnutrition is severe; thus, its usefulness in detect-ing recent protein

depletion is limited. Decreased albumin levels may be due to overhydration,

liver or renal disease, and excessive protein loss because of burns, major surgery,

infection, and cancer (Dudek, 2000). Transferrin is a protein that binds and

carries iron from the intestine through the serum. Because of its short

half-life, decreased transferrin levels respond more quickly to protein

deple-tion than albumin. Serial measurements of these, as well as preal-bumin

levels, are used to assess the results of nutritional therapy.

Although not available

from many laboratories, retinol-binding protein may be a useful means of

monitoring acute, short-term changes in protein status.

Reduced total lymphocyte

count in people who become acutely malnourished as a result of stress and

low-calorie feeding are associated with impaired cellular immunity (Dudek,

2000). Anergy, the absence of an immune response to injection of small

concentrations of recall antigen under the skin, may also indicate malnutrition

because of delayed antibody synthesis and response.

Serum electrolyte levels

provide information about fluid and electrolyte balance and kidney function.

The creatinine/height index calculated over a 24-hour period assesses the

metabolically active tissue and indicates the degree of protein depletion,

com-paring expected body mass for height and actual body cell mass.

24-hour urine sample is obtained, and the amount of creati-nine is measured and compared to normal ranges based on the patient’s height and gender. Values less than normal may indicate loss of lean body mass and protein malnutrition.

CLINICAL EXAMINATION

The state of nutrition

is often reflected in a person’s appearance. Although the most obvious physical

sign of good nutrition is a normal body weight with respect to height, body

frame, and age, other tissues can serve as indicators of general nutritional

status and adequate intake of specific nutrients; these include the hair, skin,

teeth, gums, mucous membranes, mouth and tongue, skeletal muscles, abdomen,

lower extremities, and thyroid gland (Table 5-2). Specific aspects of clinical

examination useful in identifying nutritional deficits include oral examination

and as-sessment of skin for turgor, edema, elasticity, dryness, subcuta-neous

tone, poorly healing wounds and ulcers, purpura, and bruises. The

musculoskeletal examination also provides informa-tion about muscle wasting and

weakness.

DIETARY DATA

The appraisal of food

intake considers the quantity and quality of the diet and also the frequency

with which certain food items and nutrients are consumed. Commonly used methods

of deter-mining individual eating patterns include the food record and the

24-hour food recall, which can help estimate if the food intake is adequate and

appropriate. If these methods are used, instructions about measurement and

recording food intake are given when the patient’s dietary history is obtained.

Food Record

The food record is used

most often in nutritional status studies. The person is instructed to keep a

record of food actually con-sumed over a period of time, varying from 3 to 7

days, and to ac-curately estimate and describe the specific foods consumed.

Food records are fairly accurate if the person is willing to provide fac-tual

information and able to estimate food quantities.

24-Hour Recall

The 24-hour recall

method is, as the name implies, a recall of food intake over a 24-hour period.

The person is asked by the in-terviewer to recall all food eaten during the

previous day and to estimate the quantities of the food consumed. Because

informa-tion does not always represent usual intake, at the end of the

in-terview the patient is asked if the previous day’s food intake was a typical

one. To obtain supplementary information about the typical diet, the

interviewer also asks how frequently the person eats foods from the major food

groups.

CONDUCTING THE DIETARY INTERVIEW

The success of the interviewer in obtaining information for di-etary assessment depends on effective communication, which re-quires that good rapport be established to promote respect and trust. The interviewer explains the purpose of the interview. It is conducted in a nondirective and exploratory way, allowing the respondent to express feelings and thoughts while encouraging him or her to answer specific questions. The manner in which questions are asked will influence the respondent’s cooperation. Thus, the interviewer must be nonjudgmental and avoid ex-pressing disapproval, either verbally or by facial expression.

Character of General Intake

Several questions may be

necessary to elicit the information needed. When attempting to elicit information

about the type and quan-tity of food eaten at a particular time, the

interviewer avoids lead-ing questions, such as, “Do you use sugar or cream in

your coffee?” Also, assumptions are not made about the size of servings;

instead, questions are phrased so that quantities are more clearly deter-mined.

For example, to help determine the size of one hamburger eaten, the patient may

be asked, “How many servings were pre-pared with the pound of meat you bought?”

Another approach to determining quantities is to use food models of known sizes

in es-timating portions of meat, cake, or pie or to record quantities in common

measurements, such as cups or spoonfuls (or according to the size of

containers, when discussing intake of bottled beverages).

In recording a particular

combination dish, such as a casserole, it is useful to ask for the ingredients

in the recipe, recording the largest quantities first. When recording

quantities of ingredients, one notes whether the food item was raw or cooked

and the number of servings provided by the recipe. When the client lists the

foods for the recall questionnaire, it may be helpful to read back the list of

foods and ask if anything was forgotten, such as fruit, cake, candy,

between-meal snacks, or alcoholic beverages.

Additional information

obtained during the interview should include methods of preparing food, sources

available for food (donated foods, food stamps), food-buying practices, vitamin

and mineral supplements, and income range.

Cultural and Religious Considerations

An individual’s culture

determines to a large extent which foods are eaten and how they are prepared

and served. Culture and reli-gious practices together often determine if

certain foods are pro-hibited and if certain foods and spices are eaten on certain

holidays or at specific family gatherings. Because of the importance of culture

and religious beliefs to many individuals, it is important to be sensitive to

these factors when obtaining a dietary history. It is, however, equally

important not to stereotype individuals and assume that because they are from a

certain culture or religious group, they adhere to specific dietary customs.

Culturally sensitive

materials, such as the food pagoda, are available for making appropriate

dietary recommendations (The Chinese Nutrition Society, 1999).

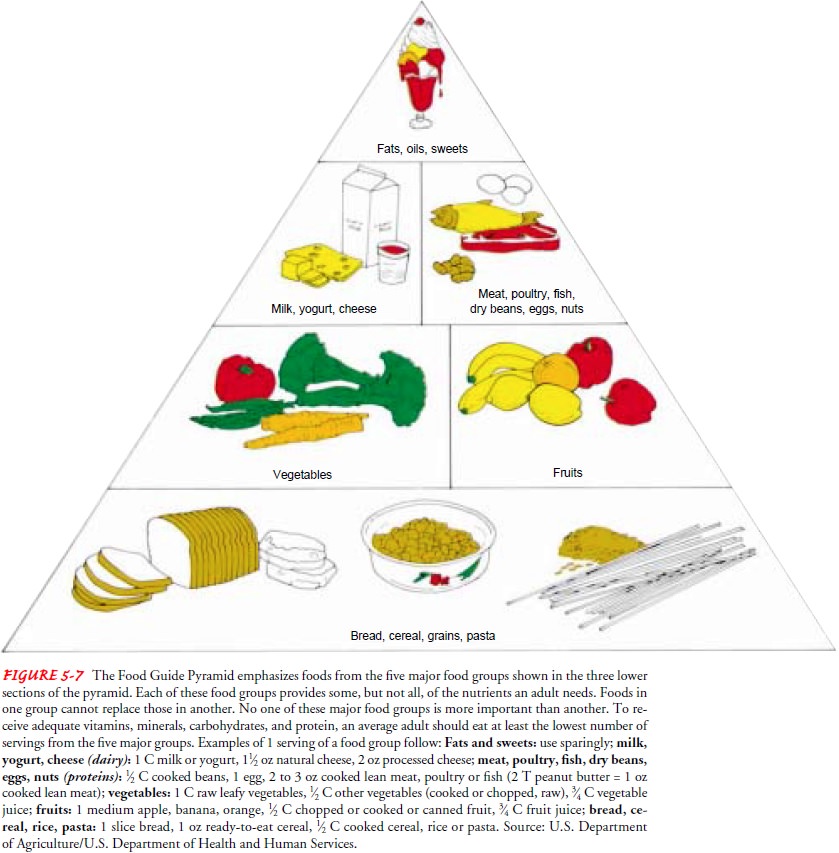

EVALUATING THE DIETARY INFORMATION

After the dietary

information has been obtained, the nurse evalu-ates the patient’s dietary

intake. If the goal is to determine if the per-son generally eats a healthful

diet, the food intake may be compared to the dietary guidelines outlined in the

USDA’s Food Guide Pyra-mid (Fig. 5-7). The pyramid divides foods into five

major groups and offers recommendations for variety in the diet, proportion of

food from each food group, and moderation in eating fats, oils, and sweets. The

person’s food intake is compared with recommenda-tions based on various food

groups for various age levels.

If the nurse or

dietitian is interested in knowing about the in-take of specific nutrients,

such as vitamin A, iron, or calcium, the patient’s food intake is analyzed by

consulting a list of foods and their composition and nutrient content. The diet

is then analyzed in terms of grams and milligrams of specific nutrients. The

total nutritive value is then compared with the recommended dietary allowances

that are specific for different age categories, gender, and special

circumstances such as pregnancy or lactation (Monsen, 2000). The nurse

frequently participates in the nutrition screen-ing of patients and

communicates the information to the dieti-tian and the rest of the team for

more detailed assessment and for clinical nutrition intervention.

FACTORS INFLUENCING NUTRITIONAL STATUS IN VARIED SITUATIONS

One sensitive indicator

of the body’s gain or loss of protein is its nitrogen balance. An adult is said

to be in nitrogen equilibrium when the nitrogen intake (from food) equals the

nitrogen output

A positive nitrogen balance exists when

nitrogen intake exceeds nitrogen output and indicates tissue growth, such as

occurs during preg-nancy, childhood, recovery from surgery, and rebuilding of

wasted tissue. Negative nitrogen balance indicates that tissue is breaking down

faster than it is being replaced. In the absence of an adequate intake of

protein, the body converts protein to glucose for energy. This can occur with

fever, starvation, surgery, burns, and debili-tating diseases. Each gram of

nitrogen loss in excess of intake rep-resents the depletion of 6.25 g of

protein or 25 g of muscle tissue. Therefore, a negative nitrogen balance of 10

g/day for 10 days could mean the wasting of 2.5 kg (5.5 lb) of muscle tissue as

it is converted to glucose for energy.

When conditions that

result in negative nitrogen balance are coupled with anorexia (loss of

appetite), they can lead to malnutrition. Malnutrition interferes with wound

healing, in-creases susceptibility to infection, and contributes to an

in-creased incidence of complications, longer hospital stay, and prolonged

confinement of the patient to bed (Bender, Pusateri, Cook et al., 2000).

The patient who is

hospitalized may have an inadequate di-etary intake because of the illness or

disorder that necessitated the hospital stay or because the hospital’s food is

unfamiliar or unap-pealing (Dudek, 2000; Wilkes, 2000). The person who is cared

for at home may feel too sick or fatigued to shop and prepare food or may be

unable to eat because of other physical problems or limitations. Limited or

fixed incomes or the high costs of med-ications may result in insufficient

money to buy nutritious foods. Patients with inadequate housing or inadequate

cooking facilities are unlikely to have an adequate nutritional intake.

Because complex

treatments (eg, ventilators, intravenous in-fusions, chemotherapy) once used

only in the hospital setting are now being provided in the home and outpatient

settings, nutri-tional assessment of the patient in these settings is an

important aspect of home and community-based care as well as hospital-based

care (Dabrowski & Rombeau, 2000; Worthington, Gilbert & Wagner, 2000).

Many medications

influence nutritional status by suppress-ing the appetite, irritating the

mucosa, or causing nausea and vomiting. Others may influence bacterial flora in

the intestine or directly affect nutrient absorption so that secondary

mal-nutrition results. People who must take many medications in a single day

often report feeling too full to eat. The person’s use of prescription and

over-the-counter medications and their ef-fect on appetite and dietary intake

are assessed. Many of the fac-tors that contribute to poor nutritional status

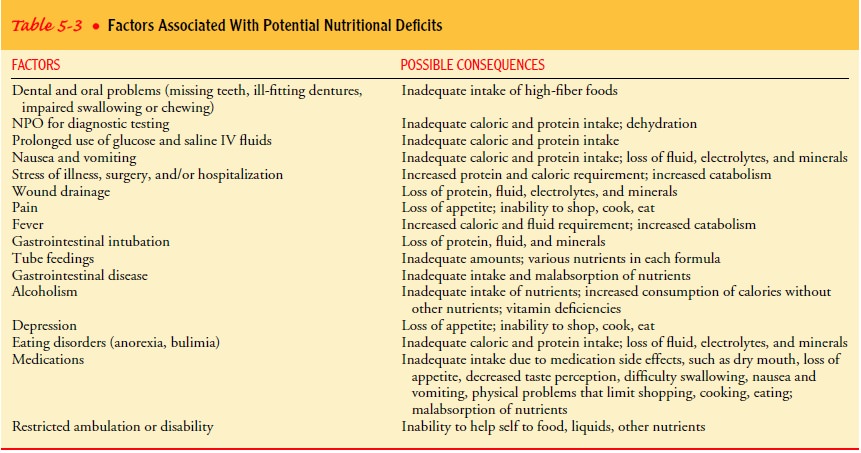

are identified in Table 5-3.

ANALYSIS OF NUTRITIONAL STATUS

Measurement of BMI and

biochemical, clinical, and dietary data are used together to determine the

patient’s nutritional status. Often the BMI, biochemical measures, and dietary

data provide more information about the patient’s nutritional status than the

clinical examination; the clinical examination may not detect subclinical

deficiencies unless such deficiencies become so ad-vanced that overt signs

develop. A low intake of nutrients over a period of time may lead to low

biochemical levels and without nutritional intervention may result in

characteristic and observ-able signs and symptoms (see Table 5-2). A plan of

action for nu-tritional intervention is based on the results of the dietary

assessment and the patient’s profile. To be effective, the plan must meet the

patient’s need for a balanced diet, maintain or con-trol weight, and compensate

for increased nutritional needs.

Adolescent

Considerations

Adolescence is a time of

critical growth and acquisition of lifelong eating habits, and therefore

nutritional assessment and analysis are critical. In the past two decades the

percentage of adolescents who are overweight has almost tripled (USDHHS, 2001).

De-spite this, total milk consumption has decreased by 36% com-pared to prior

years (Cavadini, Siega-Riz & Popkin, 2000). Fruit and vegetable consumption

is also below the recommended five servings per day.

Adolescent girls are at

particular nutritional risk as iron, folate, and calcium intake is below

recommended levels (Cavadini, Siega-Riz & Popkin, 2000). Persons with other

nutritional disorders, such as anorexia and bulimia, have a better chance for

recovery if these disorders are identified in the adolescent years compared to

adulthood (Orbanic, 2001).

Related Topics