Chapter: Essentials of Anatomy and Physiology: The Human Organism

Terminology and the Body Plan

When you begin to study anatomy and physiology, the number of new words may seem overwhelming. Learning is easier and more interesting if you pay attention to the origin, or etymology (et′ĕ-mol′o-jē), of new words. Most of the terms are derived from Latin or Greek. For example, anterior in Latin means “to go before.” Therefore, the anterior surface of the body is the one that goes before when we are walking.

Words are often modified by adding a prefix or suffix. For example, the suffix -itis means an inflammation, so appendicitis is an inflammation of the appendix. As new terms are introduced in this text, their meanings are often explained. The glossary and the list of word roots, prefixes, and suffixes on the inside back cover of the textbook also provide additional information about the new terms.

Body Positions

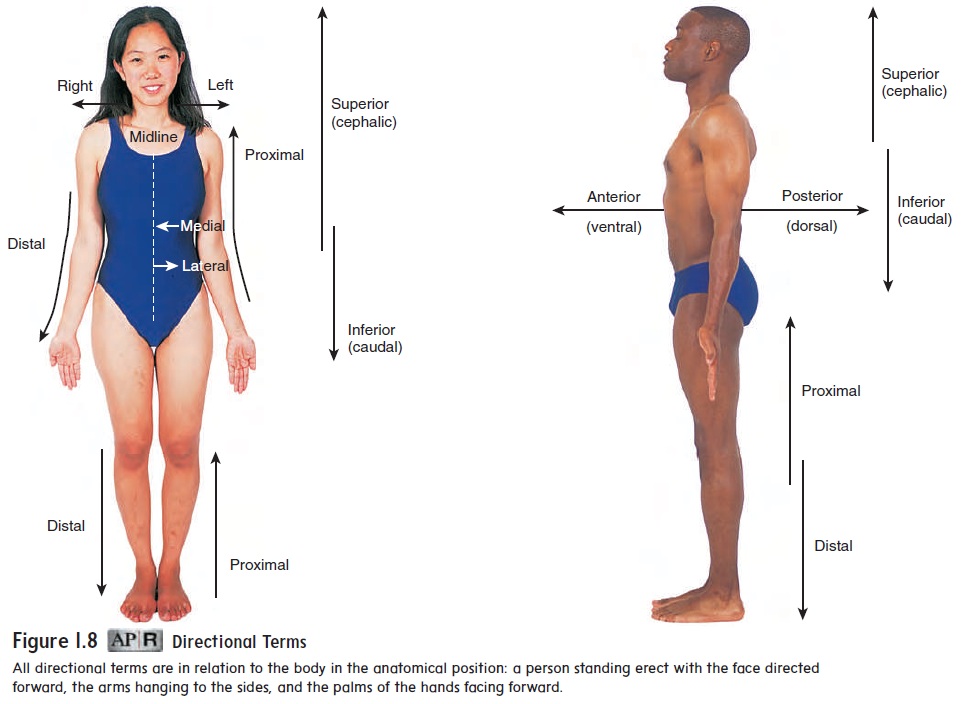

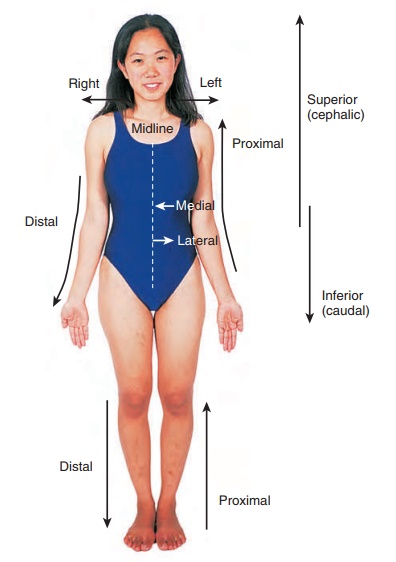

The anatomical position refers to a person standing erect with the face directed forward, the upper limbs hanging to the sides, and the palms of the hands facing forward (figure 1.8). A person is supine when lying face upward and prone when lying face downward.

The position of the body can affect the description of body parts relative to each other. In the anatomical position, the elbow is above the hand, but in the supine or prone position, the elbow and hand are at the same level. To avoid confusion, relational descrip-tions are always based on the anatomical position, no matter the actual position of the body.

Directional Terms

Directional terms describe parts of the body relative to each other (figure 1.8 and table 1.1). It is important to become familiar with these directional terms as soon as possible because you will see them repeatedly throughout the text. Right and left are used as directional terms in anatomical terminology. Up is replaced by superior,down by inferior,front by anterior, and back by posterior.

As previously mentioned, the word anterior means that which goes before; the word ventral means belly. Therefore, the anterior surface of the human body is also called the ventral surface, or belly, because the belly “goes first” when we are walking. The word posterior means that which follows, and dorsal means back. Thus, the posterior surface of the body is the dorsal surface, or back, which follows as we are walking.

Medial means toward the midline, and lateral means awayfrom the midline. The nose is located in a medial position on the face, and the ears are lateral to the nose. The term superficial refers to a structure close to the surface of the body, and deep is toward the interior of the body. For example, the skin is superficial to muscle and bone.

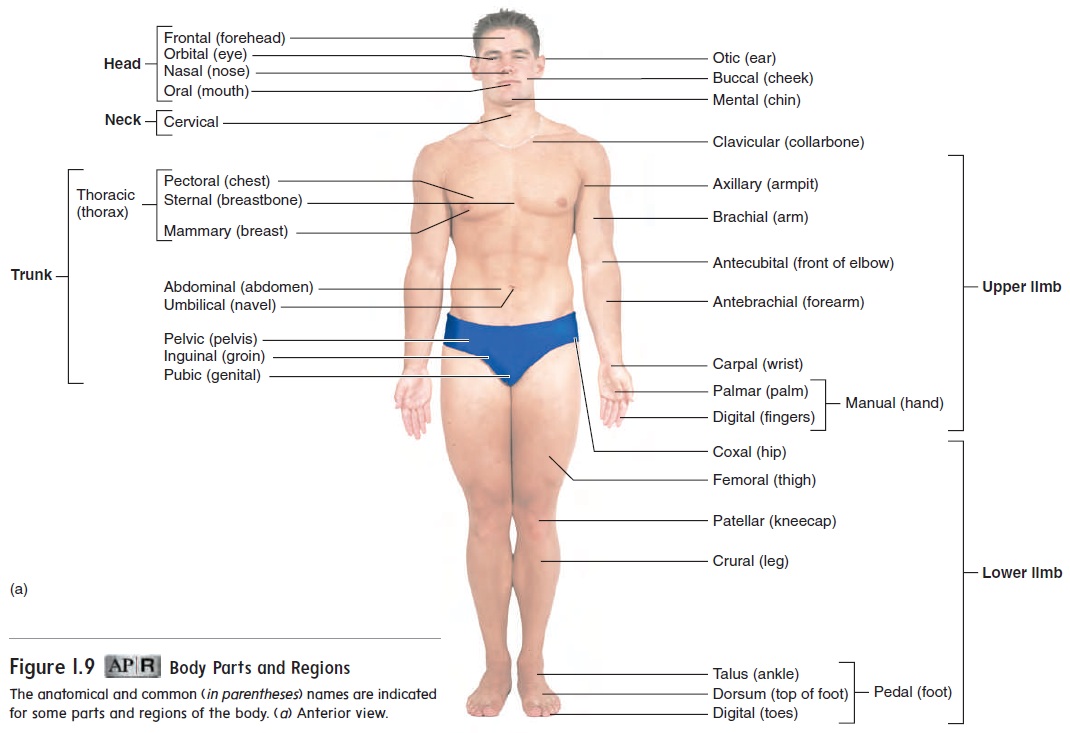

Body Parts and Regions

Health professionals use a number of terms when referring to dif-ferent regions or parts of the body. Figure 1.9 shows the anatomical terms, with the common terms in parentheses. The central region of the body consists of the head, neck, and trunk. The trunk can be divided into the thorax (chest), abdomen (region between the thorax and pelvis), and pelvis (the inferior end of the trunk associated with the hips). The upper limb is divided into the arm, forearm, wrist, and hand. The arm extends from the shoulder to the elbow, and the forearm extends from the elbow to the wrist. The lower limb is divided into the thigh, leg, ankle, and foot. The thigh extends from the hip to the knee, and the leg extends from the knee to the ankle. Note that, contrary to popular usage, the terms arm and leg refer to only a part of the respective limb.

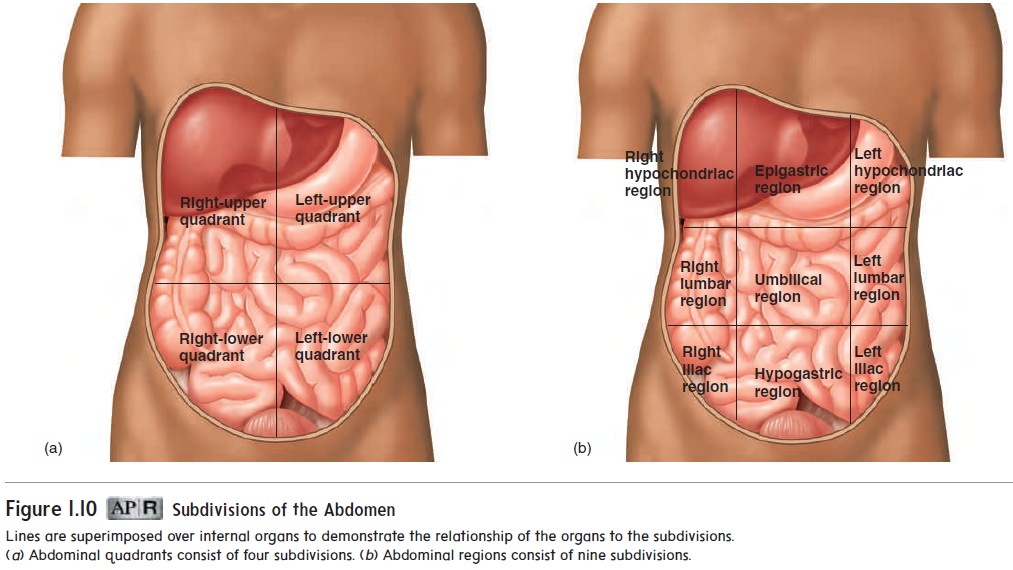

The abdomen is often subdivided superficially into four sections, or quadrants, by two imaginary lines—one horizontal and one vertical—that intersect at the navel (figure 1.10a). The quadrants formed are the right-upper, left-upper, right-lower, and left-lower quadrants. In addition to these quadrants, the abdo-men is sometimes subdivided into regions by four imaginary lines—two horizontal and two vertical. These four lines create an imaginary tic-tac-toe figure on the abdomen, resulting in nine regions: epigastric (ep-i-gas′trik), right and left hypochondriac(hı̄-pō-kon′drē-ak), umbilical (ŭm-bil′i-kăl), right and left lumbar (lŭm′bar), hypogastric (hı̄-pō-gas′trik), and right and left iliac (il′ē-ak) (figure 1.10b). Clinicians use the quadrants or regions as reference points for locating the underlying organs. For example, the appendix is in the right-lower quadrant, and the pain of an acute appendicitis is usually felt there.

Planes

At times, it is conceptually useful to discuss the body in reference to a series of planes (imaginary flat surfaces) passing through it (figure 1.11). Sectioning the body is a way to “look inside” and observe the body’s structures. A sagittal (saj′i-tăl) plane runs vertically through the body and separates it into right and left parts. The word sagittal literally means the flight of an arrow and refers to the way the body would be split by an arrow passing ante-riorly to posteriorly. A median plane is a sagittal plane that passes through the midline of the body, dividing it into equal right and left halves. A transverse (trans-vers′) plane, or horizontal plane, runs parallel to the surface of the ground, dividing the body into superior and inferior parts. A frontal plane, or coronal (kōr′ŏ-năl, kō-rō′nal; crown) plane, runs vertically from right to left and divides the body into anterior and posterior parts.

Organs are often sectioned to reveal their internal structure (figure 1.12). A cut through the long axis of the organ is a longi\tudinal section, and a cut at a right angle to the long axis is a transverse section, orcross section.If a cut is made across thelong axis at other than a right angle, it is called an oblique section.

Body Cavities

The body contains many cavities. Some of these cavities, such as the nasal cavity, open to the outside of the body, and some do not. The trunk contains three large cavities that do not open to the outside of the body: the thoracic cavity, the abdominal cavity, and the pelvic cavity (figure 1.13). The thoracic cavity is surrounded by the rib cage and is separated from the abdominal cavity by the muscular diaphragm. It is divided into right and left parts

by a median structure called the mediastinum (me′dē -as-t ′n̆u m; wall). The mediastinum is a partition containing the heart, the thymus, the trachea, the esophagus, and other structures. The two lungs are located on each side of the mediastinum.

The abdominal cavity is bounded primarily by the abdomi-nal muscles and contains the stomach, the intestines, the liver, the spleen, the pancreas, and the kidneys. The pelvic (pel′vik) cavity is a small space enclosed by the bones of the pelvis and contains the urinary bladder, part of the large intestine, and the internal reproductive organs. The abdominal and pelvic cavities are not physically separated and sometimes are called the abdominopelvic (ab-dom′i-nō -pel′vik) cavity.

Serous membranes

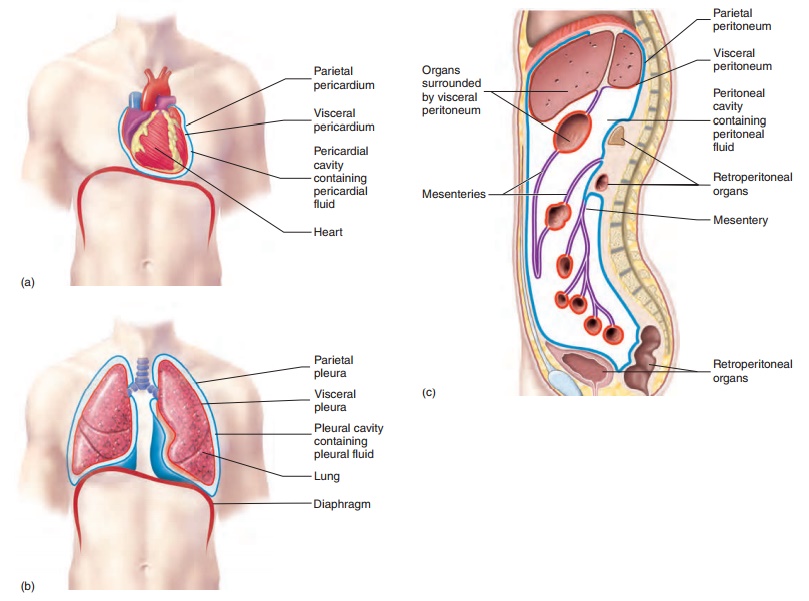

Serous (s̄er′̆us) membranes line the trunk cavities and cover theorgans of these cavities. To understand the relationship between serous membranes and an organ, imagine pushing your fist into an inflated balloon. The inner balloon wall in contact with your fist (organ) represents the visceral (vis′er-̆a l; organ) serous membrane, and the outer part of the balloon wall represents the parietal (p̆a -r ′ĕ - tă l; wall)serous membrane (figure 1.14). The cavity, or space, between the visceral and parietal serous membranes is normally filled with a thin, lubricating film of serous fluid produced by the mem-branes. As an organ rubs against another organ or against the body wall, the serous fluid and smooth serous membranes reduce friction.

The thoracic cavity contains three serous membrane-lined cavities: a pericardial cavity and two pleural cavities. The peri-cardial (per-i-kar′dē-ăl; around the heart) cavity surrounds theheart (figure 1.15a). The visceral pericardium covers the heart, which is contained within a connective tissue sac lined with the parietal pericardium. The pericardial cavity, which contains peri-cardial fluid, is located between the visceral pericardium and the parietal pericardium.

A pleural (ploor′̆a l; associated with the ribs) cavity surrounds each lung, which is covered by visceral pleura (figure 1.15b). Parietal pleura lines the inner surface of the thoracic wall, the lateral surfaces of the mediastinum, and the superior surface of the dia-phragm. The pleural cavity is located between the visceral pleura and the parietal pleura and contains pleural fluid.

The abdominopelvic cavity contains a serous membrane-lined cavity called the peritoneal (per′i-t̄o -n̄e ′̆a l; to stretch over) cavity (figure 1.15c). Visceral peritoneum covers many of the organs of the abdominopelvic cavity. Parietal peritoneum lines the wall of the abdominopelvic cavity and the inferior surface of the diaphragm. The peritoneal cavity is located between the visceral peritoneum and the parietal peritoneum and contains peritoneal fluid.

The serous membranes can become inflamed—usually as a result of an infection. Pericarditis (per′i-kar-d̄ı ′tis) is inflammation of the pericardium, pleurisy (ploor′i-s̄e ) is inflammation of the pleu-ra, and peritonitis (per′i-t̄o -n̄ı ′tis) is inflammation of the peritoneum.

Mesenteries (mes′en-ter-ēz), which consist of two layersof peritoneum fused together (figure 1.15c), connect the visceral peritoneum of some abdominopelvic organs to the parietal peri-toneum on the body wall or to the visceral peritoneum of other abdominopelvic organs. The mesenteries anchor the organs to the body wall and provide a pathway for nerves and blood vessels to reach the organs. Otherabdominopelvic organs are more closely attached to the body wall and do not have mesenteries. Parietal peritoneum covers these other organs, which are said to be retroperitoneal (re′trō-per′i-tō-nē′ăl;retro,behind). The retroperi-toneal organs include the kidneys, the adrenal glands, the pancreas, parts of the intestines, and the urinary bladder (figure 1.15c).

Related Topics