Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Individual Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy

Tasks of the Psychoanalytic Psychotherapist

Tasks

of the Psychoanalytic Psychotherapist

What are

the challenges of the psychotherapist in performing psychoanalytic

psychotherapy? First, the therapist must ensure that the patient can feel both

emotionally and physically safe within the therapeutic relationship. This is

accomplished by ac-knowledging the goals of the treatment and defining the role

of the therapist and through establishing professional boundaries. Boundaries

refer to those constant and highly predictable com-ponents of the treatment

situation that constitute the framework of the working relationship. For

example, agreeing to meet withthe patient for a specified amount of time, in a

professional office, and for an established fee are some of the elements of the

profes-sional framework.

Boundaries

also have ethical dimensions best summarized as the absolute adherence by the

therapist to the rule of never taking advantage of the patient: through sexual

behavior; for per-sonal, financial, or emotional gain; or by exploiting the

patient’s need and love for the therapist in any fashion (e.g., by using the

therapy sessions to discuss the therapist’s own problems). The concepts of

neutrality, abstinence and confidentiality further de-fine the role of the

therapist. A critical task of the psychoanalytic psychotherapist is to detect

when a breach in either role or bound-ary has occurred and to restore the

patient’s security through clarifying and interpreting the meaningfulness of

such a breach.

The

explication of a boundary violation is but one spe-cific example of the technique

of interpretation. Successful in-terpretation is based on a number of

prerequisite skills. These include the capacity to empathize with the patient’s

plight, the ability to recognize the meaning of one’s own fantasies about, and

responses to, a patient (countertransference), the ability to maintain the

patient’s verbal flow through the use of open-ended or focused questions, and

the capacity to tolerate a relatively high level of ambiguity within the

therapeutic relationship. One im-portant professional characteristic of the

skilled psychotherapist is patience. Psychotherapy is often arduous, and the

capacity to “stay in the chair” with the patient is critical.

The

identification of repeated patterns of behavior both within the therapy and in

the patient’s outside life is a funda-mental technique in making sense of the

patient’s emotional life. This, of course, involves the appreciation of

transference and the art of knowing how and when to share this recognition with

the patient. Interpretation relies on both appropriate timing and dos-age. That

is, the psychoanalytic psychotherapist must appreciate when the patient can

best integrate the therapist’s observations and must respect the patient’s

defenses, taking care not to over-whelm the patient by insisting that she or he

confront more than is tolerable.

Psychoanalytic

psychotherapy requires the successful en-gagement of the patient and the

establishment of a therapeutic or working alliance. The alliance can be

threatened by a number of phenomena including, but not limited to, the

following

·

The therapist’s countertransferences or other

limitations in his or her capacity to tolerate the emotions stirred by the

patient, resulting in empathic failures and mistakes.

·

The emergence of intense feelings and needs within

the pa-tient, for example, when an accurate well-timed intervention evokes

feelings in relation to the therapist of appreciation and love accompanied by

feelings of vulnerability, erotic desire, or inferiority which the patient

wants to flee.

·

The patient’s being reminded of the existence of

others in the therapist’s life, such as other patients or family (e.g., during

in-terruptions due to the therapist’s vacations), triggering painful and

embarrassing feelings of jealousy and possessiveness.

The

therapist’s ability to appreciate and respectfully to acknowl-edge to the

patient the impact of these temporal events is critical to the progress of

treatment.

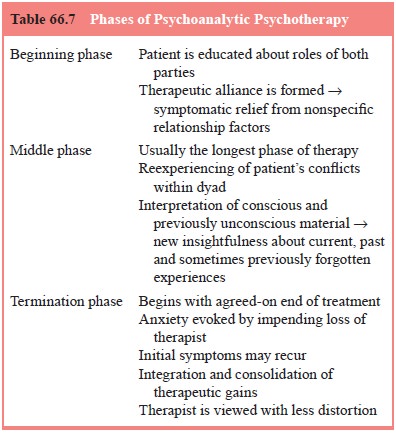

All of

the psychotherapist’s skills and techniques must be embedded in a consistent

and coherent theoretical viewpoint that provides the therapist with a framework

to understand the eti-ology and meaning of a patient’s symptoms and

dysfunctional behaviors both in the past and in the present in each of the

phases of psychotherapy (Table 66.7).

This

includes an organized method for understanding the therapist’s unconscious and

conscious responses to the patient as well. It requires that the therapist

listen to the patient’s commu-nications in a manner that is markedly different

from other forms of social discourse. So-called “process communication” speaks

to the therapist on multiple levels and through displacement, through passing

remarks and jokes, through shifts in topics, and through metaphors and symbols.

To assist in understanding com-plicated process communication, psychiatrists

often ask them-selves, Why is the patient telling me this now? What might the

patient be trying to say about his or her uncomfortable feelings? Is something

being said about the therapeutic relationship?

The objective

of this type of treatment is to improve the patient’s quality of life largely

through enhancing interpersonal relationships by promoting greater insight into

perceptual distor-tion and intrapsychic and interpersonal conflict.

Psychoanalytic psychotherapy accomplishes this objective by focusing on the

pa-tient’s current predicaments as manifested in both life activities and

relationship with the therapist. It is at times less concerned with the

analysis of transference and the complete discovery of the underlying genetic

precursors of the patient’s current psycho-logical problems, depending on the

specific clinical situation.

Related Topics