Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Individual Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy

Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy: Basic Technique

Basic

Technique

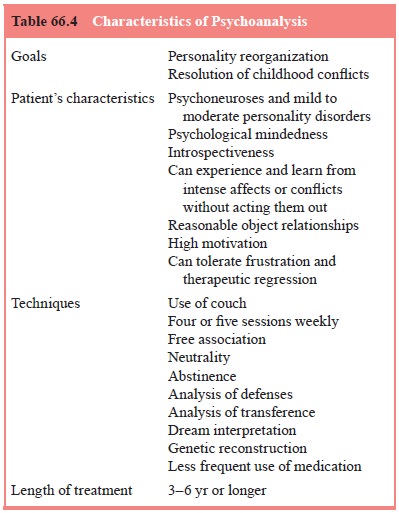

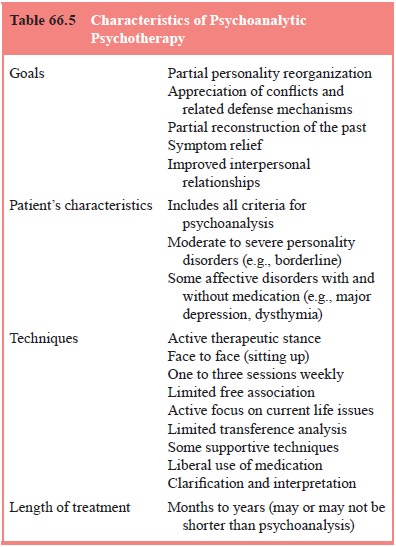

The

analysis of transference by the interpretation of resistance is important for

the psychoanalytic psychotherapist. To promote the patient’s examination of the

phenomena of transference and resistance, both the analyst and the therapist

are guided by prin-ciples that establish a confidential, safe and predictable

environ-ment geared toward maximizing the patient’s introspection and focus on

the therapeutic relationship. The patient is encouraged to free associate, that

is, to notice and report as well as she or he can whatever comes into conscious

awareness (Tables 66.4 and 66.5).

Therapeutic

neutrality and abstinence are related concepts. Both foster the unfolding and

deepening of the transference, as well as the opportunity for its interpretation.

The psychoanalytic psychotherapist assumes a neutral position vis-à-vis the patient’s psychological

material by neither advocating for the patient’s wishes and needs nor

prohibiting against these. The patient is en-couraged in the therapeutic

relationship to develop the capacity for self-observation. Neutrality does not

mean nonresponsive-ness; it is nonjudgmental nondirectiveness.

Abstinence refers to the position assumed by the psychoan-alytic psychotherapist of recognizing and accepting the patient’s wishes and emotional needs, particularly as they emanate from transference distortions, while abstaining from direct gratifica-tion of those needs through action. Abstinence is a principle that guards against the therapist’s gratification at the patient’s ex-pense. For example, as the treatment experience deepens into a more consolidated transference neurosis, there may be a strong tendency by the patient to experience the therapist as the impor-tant person in the patient’s life around whom the characteristic conflictual issues are manifested. By maintaining a neutral and abstinent position with respect to the patient’s needs and wishes, the psychotherapist creates a safe atmosphere for the experiencing and expression of even highly charged affects, the safety required for the patient’s motivation for continued therapeutic work. The position held by the psychiatrist is neither sterile nor overstimu-lating and promotes the establishment of a meaningful therapeu-tic relationship.

The rule

of free association dictates that the patient should verbalize to the best of

her or his ability whatever comes into awareness, including thoughts, feelings,

physical sensations, memories, dreams, fears, wishes, fantasies and perceptions

of the analyst. Whereas at first glance this requirement appears to be

unscientific, in fact, the psychiatrist and patient quickly come to appreciate

that no thought or feeling is random or irrelevant but rather that all mental

content is relevant to the patient’s emotional problems. Indeed, much

productive therapeutic work is focused on those instances when the patient is

not able to speak about what is on his or her mind.

Many

psychoanalytic psychotherapists also use the tech-nique of dream

interpretation, although recently there may be less emphasis on this. Freud

placed great emphasis on the inter-pretation of dreams because he discovered

that such a technique provided insights into the working of the unconscious. In

a simi-lar fashion, slips of the tongue, jokes, puns and some types of

forgetfulness are attended to carefully by the therapist because they are

nonsleep activities that also provide insight into the pa-tient’s unconscious

mental processes. Good technique does not necessarily include pointing out to

the patient these events each time they occur, for they may often be a source

of intense embar-rassment. Rather, the slips are noted as helpful data in

assessing the patient’s inner thoughts.

All of

these techniques are embedded in a unique manner of listening to the patient’s

verbalizations within the context of the treatment situation. In particular,

two related but specific compo-nents initially attributed to the listening

process are worthy of note. First, the concept of the evenly hovering or evenly

suspended attention implies that listening to the patient requires of the

thera-pist that he or she be nonjudgmental and give equal attention to every

topic and detail that the patient provides. It also embraces the notion that

the effective therapist is one who can remain open to her or his own thoughts

and feelings as they are evoked while listening to the patient. Such internal

responses often supply im-portant insights into the patient’s concerns.

Secondly, empathic listening is of equal importance to both parties. Empathy

permits the patient to feel understood, as well as provides the therapist with

a method to achieve vicarious introspection. Indeed, one of the major

contributions of self-psychology has been the identifi-cation of empathic

listening and interpretation (the immersion by the therapist into the

subjectivity of the patient’s experience) as basic to the methodology of

psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic psychotherapy (Kohut, 1978, 1971).

Interferences to successful empathic listening are often the product of

countertransference reactions, which should be suspected whenever, for example,

the therapist experiences irritation, strong erotic feelings, or inatten-tion

during a treatment session.

Related Topics