Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Individual Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy

Gender and Ethnocultural Issues in Psychotherapy

Gender Issues in Psychotherapy

Does the

gender of the psychotherapist have any effect on the psy-chotherapeutic

relationship and treatment outcome? Are certain psychological problems best

treated by therapists whose gender is different from that of the patient? Do

different phenomena ap-pear in the treatment of those patients whose therapists

are of the same gender? Is the duration of treatment affected by the

thera-pist’s gender? Does gender have any influence on the choice of therapist

by a patient? These are important questions that have been debated in

psychotherapy and psychoanalytic literature for more than 50 years

Although

the literature regarding the advantages and dis-advantages of gender matching

of patients and therapists consists largely of anecdotal and negative reports

(Zlotnick et al., 1998), it is

nevertheless evocative. A number of common themes have emerged, including that

·

The gender of the therapist may be more critical in

supportive treatments that rely on identification with the therapist (Cave-nar

and Werman, 1983).

·

The therapist’s gender may be less important in

psychoa-nalysis than in face-to-face psychoanalytic psychotherapies because, in

the latter, the transference can be less intense (Mogul, 1982).

·

Beginning women therapists have less difficulty

with empathy but more difficulty with authority issues than do their male

counterparts (Kaplan, 1979).

Although

there is only one controlled study and it showed no difference regarding the

influence of the therapist’s gender on the therapeutic process (Zlotnick et al., 1996), there is much to

con-sider about the influence of actual gender and gender-related beliefs of

both patient and therapist on the emergence of transference and

countertransference. However, the best psychoanalytic psychother-apies will

include ample opportunities for the working through of the patient’s issues

related to important figures of both genders

Ethnocultural Issues in Psychotherapy

Culture

refers to meanings, values and behavioral norms that are learned and

transmitted in the dominant society and within its social groups. Culture

powerfully influences cognitions, feel-ing and “self” concept, as well as the

diagnostic process and treatment decisions. Ethnicity, a related concept, refers

to social groupings which distinguish themselves from other groups based on

ideas of shared descent and aspirations, as well as to behav-ioral norms and

forms of personal identity associated with such groups (Mezzich et al., 1993).

Given the

increasing multiculturalism of many cities in the USA, how should the

psychoanalytic psychotherapist treat pa-tients from cultures other than his or

her own? Whereas therapists are obligated to be culturally informed, Foulks and

colleagues (1995) have argued against the promotion of culturally specific

psychotherapies. Although acknowledging that some cross-cul-tural psychiatrists

believe expressive–supportive psychotherapy to be an ethnotherapy appropriate

only to the citizens of the West-ern world, they emphasized the overwhelming

problems in estab-lishing separate therapies and clinics devoted to patients

from a multitude of specific cultures.

Is Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy Effective?

The short

answer to this question is yes. Meta-analytical studies of psychotherapy have

demonstrated unequivocally that psycho-therapy is effective (Luborsky et al., 1975; Smith et al., 1980; Lambert et al.,

1986). The study by Smith and coworkers (1980), for example, demonstrated that

80% of those patients treated in psychotherapy fared better on outcome measures

than those who received no treatment. Psychological growth achieved through

psychotherapy is also enduring (Husby, 1985).

Cost-offset

studies have repeatedly demonstrated the help-fulness of psychotherapy in

reducing general health care services by as much as one-third (Mumford et al., 1984; Krupnick and Pincus, 1992;

Olfson and Pincus, 1994). These include reduction in hospital stays for

surgical and cardiac patients (Mumford et

al., 1982) and decreased treatment costs for those with respiratory

ill-nesses, diabetes and hypertension (Schlesinger et al., 1983). Brief psychotherapy has also been shown to be

effective in general medical clinics, where those patients with significant

medical and psychiatric problems improve substantially more than those treated

by primary care physicians alone (Meyer et

al., 1981).

Luborsky

and coworkers (1993) have demonstrated that psychoanalytic psychotherapy is as

effective as cognitive, behav-ioral, experiential, and group therapies and

hypnotherapy. For this meta-analysis, rigorous inclusion criteria were

established including, but not limited to, adequate sample size with random

assignment, suitable length and frequency of sessions, sound out-come measures,

adherence by therapists to treatment manuals, and comparable skill levels among

therapists. A number of other studies have demonstrated positive benefits in panic

disorder de-pression, personality disorder, drug abuse, eating disorders and

others (Willborg and Dahl, 1996; Bateman and Fonagy, 2001.)

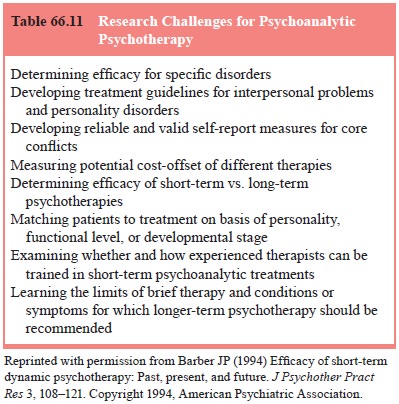

The

important research questions with respect to brief psychoanalytic psychotherapy

have been summarized by Barber (1994) and are relevant to all psychoanalytic

psychotherapies (Table 66.11).

Towards a Neurobiology of Psychotherapy

Exciting new research in psychiatry, brain imaging, cognitive neuroscience, genetics, and molecular biology has provided striking insights into how psychotherapy actually changes both brain structure and function (Liggan and Kay, 1999; Gabbard, 2000; Lehrer and Kay, 2002). Learning and memory are asso-ciated with alterations in central nervous system (CNS) neuro-nal plasticity including increased synaptic strength and number of synapses. Neurogenesis, or the creation of new brain cells, occurs daily in the human hippocampus (Eriksson et al., 1998),

the

central location for the formation of new explicit memories. Not only does memory

consolidation lead to persistent modfica-tions in synaptic plasticity, but

psychotherapy, a form of learn-ing, also produces changes in the permanent

storage of informa-tion acquired throughout an individual’s life and provides

new resources to address important psychobiological relationships between

affect, attachment and memory which is of funda-mental importance in

psychiatric disorders. Rapidly accruing knowledge about the different types of

memory and the role of the amygdala now support the influence of memories that

reside outside of the awareness of our patients (LeDoux, 1996). Implicit

memories formed in infancy and childhood persistently affect the manner in

which patients experience themselves and their worlds as manifested, for

example, in transference reactions within and outside of the therapeutic

relationship.

The study

of psychotherapy from a neurobiological per-spective is likely to provide

greater understanding of how words in the context of therapeutic relationships

can heal. It may be that there are similar mechanisms and anatomical regions

that are involved in the successful treatment of psychiatric illness with

psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy as monotherapies, as well as in the combined

treatment situation (Sacheim, 2001). It is also likely to yield a greater

understanding of pathogenesis and de-lineate helpful interventions to decrease

genetic vulnerability to emotional disorders.

Related Topics