Rise of Extremism and Swadeshi Movement | History - Swadeshi Campaign in Tamil Nadu | 12th History : Chapter 2 : Rise of Extremism and Swadeshi Movement

Chapter: 12th History : Chapter 2 : Rise of Extremism and Swadeshi Movement

Swadeshi Campaign in Tamil Nadu

Swadeshi

Campaign in Tamil Nadu

Swadeshi

movement in Tamil Nadu, notably in Tirunelveli district, generated a lot of

attention and support. While the Swadeshi movement in Tamil Nadu had an all

India flavour, with collective anger against the British rule remaining the

common thread, it was also underpinned by Tamil - pride and consciousness.

There was a deep divide in the Tamilnadu congress between the moderates and the

extremists.

(a) Development of Vernacular Oratory

Initially,

the movement was more of a reaction to the partition of Bengal and regular

meetings were held to protest the partition. The speakers, in such meetings,

spoke mostly in the vernacular language to an audience that included students,

lawyers, and labourers at that time. The shift from English oratory to

vernacular oratory was a significant development of this time, which had a huge

impact on the mass politics in Tamil Nadu.

Swadeshi

meetings at the Marina beach in Madras were a regular sight. The Moore Market

complex in Madras was another venue utilised for such gatherings. During the

period (1905-1907) there are police reports calling students dangerous and

their activities as seditious. Europeans in public places were greeted by the

students with shouts of Vande Mataram. In 1907, Bipin Chandra Pal came to

Madras and his speeches on the Madras Beach electrified the audience and won

new converts to the nationalist cause. The visit had a profound impact all over

Tamil Nadu. The public speeches in the Tamil language created an audience which

was absent during the formative years of the political activities in Tamil

Nadu.

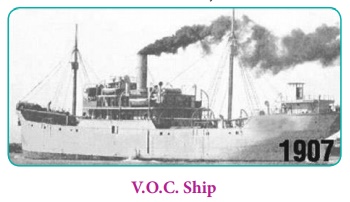

(b) V.O.C. and Swadeshi Steam Navigation Company (SSNC)

The Swadeshi movement in Tamil Nadu came

to national attention

in 1906 when V.O Chidambaram mooted the

idea of launching

a swadesh shipping venture in in opposition to the monopoly

of the British in navigation through the coast.

In 1906,

V.O.C. registered a joint stock company called The Swadeshi Steam Navigation

Company (SSNC) with a capital of Rs 10 Lakh, divided into 40,000 shares of Rs.

25 each.

Shares

were open only to Indians, Ceylonese and other Asian nationals. V.O.C. purchased

two steamships, S.S. Gallia and S.S. Lawoe. When in the other parts of India,

the response to Swadeshi was limited to symbolic gestures of making candles and

bangles, the idea of forging a Swadeshi Steam Navigation Company was really

spectacular. V.O.C invoked the rich history of the region and the maritime

glory of India’s past and used it as a reference point to galvanize the public

opinion in favour of a Swadeshi venture in the sea.

The

initiative of V.O.C. was lauded by the national leaders. Lokmanya Tilak wrote

about the success of the Swadeshi Navigation Company in his papers Kesari and Mahratta. Aurobindo Ghose also lauded the Swadeshi efforts and

helped to promote the sale of shares of the company. The major shareholders

included Pandithurai and Haji Fakir Mohamed.

The

initial response of the British administration was to ignore the Swadeshi

company. As patronage for Swadeshi Company increased, the European officials

exhibited blatant bias and racial partiality against the Swadeshi steamship.

(c) The Coral Mill Strike

After

attending the session of the Indian National Congress at Surat, V.O.C. on his

return decided to work on building a political organisation. While looking for

an able orator, he came across Subramania Siva, a swadeshi preacher. From

February to March 1907, both the leaders addressed meetings almost on a daily

basis at the beach in Tuticorin, educating the people about swadeshi and the

boycott campaign. The meetings were attended by thousands of people. These

public gatherings were closely monitored by the administration.

In 1908,

the abject working and living conditions of the Coral Mill workers attracted

the attention of V.O.C and Siva. In the next few days, both the leaders

addressed the mill workers. In March 1908, the workers of the Coral Cotton

Mills, inspired by the address went on strike. It was one of the earliest

organised labour agitations in India.

The

strike of the mill workers was fully backed by the nationalist newspapers. The

mill owners, however, did not budge and was supported by the government which

had decided to suppress the strike. To further increase the pressure on the

workers, the leaders were prohibited from holding any meetings in Tuticorin.

Finally, the mill owners decided to negotiate with the workers and concede

their demands.

This

victory of the workers generated excitement among the militants in Bengal and

it was hailed by the newspapers in Bengal. For instance, Aurobindo Ghosh’s

Bande Matram hailed the strike as “forging a bond between educated class and

the masses, which is the first great step towards swaraj…. Every victory of

Indian labour is a victory for the nation….”

(d) Subramania Bharati: Poet and Nationalist

The

growth of newspapers, both in English and Tamil language, aided the swadeshi

movement in Tamil Nadu. G. Subramaniam was one of the first among the leaders to use newspapers

to spread the nationalist message across a larger audience. Subramaniam, along

with five others, founded The Hindu

(in English) and Swadesamitran (which

was the first ever Tamil daily). In 1906 a book was published by Subramaniam to

condemn the British actions during the Congress Conference in Barsal. Swadesamitran extensively reported

nationalist activities, particularly

the news regarding V.O.C. and his speeches in Tuticorin.

Subramania

Bharati became the sub-editor of Swadesamitran

around the time (1904) when Indian nationalism was looking for a fresh

direction. Bharati was also editing Chakravartini,

a Tamil monthly devoted to the cause

of Indian women.

Two

events had a significant impact on Subramania Bharati. A meeting in 1905 with

Sister Nivedita, an Irish woman and a disciple of Vivekananda, whom he referred

to as Gurumani (teacher), greatly inspired his nationalist ideals. The churning

within the Congress on the nature of engagement with the British rule was also

a contributory factor. As discussed earlier in this lesson, the militants

ridiculed the mendicancy of the moderates who wanted to follow the

constitutional methods. Bharati had little doubt, in his mind, that the British

rule had to be challenged with a fresh approach and methods applied by the

militant nationalists appealed to him more. For instance, his fascination with

Tilak grew after the Surat session of the Congress in 1907. He translated into

Tamil Tilak’s Tenets of the New Party and a booklet on the

Madras militants’ trip to the Surat

Congress in 1907. Bharati edited a Tamil weekly India, which became the voice of the radicals.

(e) Arrest and imprisonment of V.O.C. and Subramania Siva

On March 9, 1907, Bipin Chandra Pal was released from prison after serving a six-month jail sentence.The swadeshi leaders in Tamil Nadu planned to celebrate the day of his release as ‘Swarajya Day’ in Tirunelveli. The local administration refused permission. V.O.C., Subramania Siva and Padmanabha Iyengar defied the ban and went ahead. They were arrested on March 12, 1908, on charges of sedition.

The local

public, angered over the arrest of the prominent swadeshi leaders, reacted

violently. Shops were closed in a general show of defiance. The municipality

building and the police station in Tirunelveli were set on fire. More

importantly, the mill workers came out in large numbers to protest the arrest

of swadeshi leaders. After a few incidents of confrontation with the protesting

crowd, the police open fired, and four people were killed.

On 7 July

1908, V.O.C. and Subramania Siva were found guilty and imprisoned on charges of

sedition. Siva was awarded a sentence of 10 years of transportation for his

seditious speech whereas V.O.C. got a life term (20 years) for abetting him.

V.O.C. was given another life sentence for his own seditious speech. This

draconian sentence reveals how seriously the Tirunelveli agitation was viewed by

the government.

In the

aftermath of this incident, the repression of the British administration was

not limited to the arrest of a few leaders. In fact, people who had actively

participated in the protest were also punished and a punitive tax was imposed

on the people of Tirunelveli and Tuticorin.

Excerpts from the Judgment in the case of King Emperor versus

V.O.C. and Subramania Siva (4 November 1908).“It seems to me that sedition at

any time is a most serious offense. It is true that the case is the first of

its kind in the Presidency, but the present condition of other Presidencies

where the crime seems to have secured a foothold would seem to indicate that

light sentences of imprisonment of a few months or maybe a year or two are

instances of misplaced leniency. ...The first object of a sentence is that it

shall be deterrent not to the criminal alone but to others who feel any

inclination to follow his example. Here we have to deal with a campaign of

sedition which nearly ended in revolt. The accused are morally responsible for

all the lives lost in quelling the riots that ensured on their arrest”.

(f) Ashe Murder

Repression

of the Swadeshi efforts in Tuticorin and the subsequent arrest and humiliation

of the swadeshi leaders generated anger among the youth. A plan was hatched to

avenge the Tirunelveli event. A sustained campaign in the newspapers about the

repressive measures of the British administration also played a decisive role

in building people’s anger against the administration.

In June

1911, the collector of Tirunelveli, Robert Ashe, was shot dead at Maniyachi

Railway station by Vanchinathan. Born in the Travancore state in 1880, he was

employed as a forest guard at Punalur in the then Travancore state. He was one

of the members of a radical group called Bharata Mata Association. The aim of

the association was to kill the European officers and inspire Indians to

revolt, which they believed would eventually lead to Swaraj. Vanchinathan was

trained in the use of a revolver, as part of the mission, by V.V. Subramaniam

in Pondicherry.

After shooting Ashe

at the Maniyachi Junction, Vanchinathan shot himself with the same pistol. A

letter was found in his pocket which helps to understand the strands of

inspiration for the revolutionaries like Vanchinathan.

The aftermath of the Assassination

During

the course of the trial, the British government was able to establish that

V.V.S and other political exiles in Pondicherry were in close and active

association with the accused in the Ashe murder conspiracy. The colonial

administration grew more suspicious with the Pondicherry groups and their

activities. Such an atmosphere further scuttled the possibility of

nationalistic propaganda and their activities in Tamil Nadu. As a fall-out of

the repressive measure taken by the colonial government, the nationalist

movement in Tamil Nadu entered a period of lull and some sort of revival

happened only with the Home Rule Movement in 1916.

Related Topics