Chapter: Essential Clinical Immunology: Immunological Aspects of Allergy and Anaphylaxis

Skin Diseases and Allergy

SKIN DISEASES AND ALLERGY

Case 9.2 Skin Reactions

A.A. is a fifty-six-year-old female who was well until she began to develop acute, episodic, or transient swelling of her skin (urticaria), with intense pru-ritis (itching) and erythema (redness)

She assumed she had food allergies, so she tried to eliminate various substances from her diet, including dairy products, fish, and nuts without any positive response. Eventually, she took antihis-tamines, with marginal improvement and sought medical attention after a three-month ordeal. An extensive his-tory was taken and allergy tests (all negative) and a variety of serum stud-ies were performed. She was diagnosed with a thyroid abnormality. She was referred to an endocrinologist and did well on therapy, which had nothing to do with an allergic diathesis

Urticaria and Angioedema

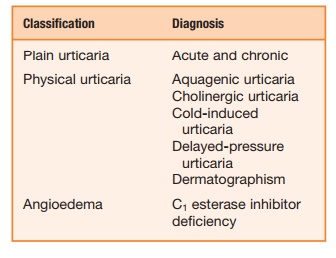

Angioedema and urticaria are two of the more perplexing problems evaluated by physicians, and cases of chronic urticaria (hives of more than six weeks duration) may yield diagnoses in about 20 percent of those evaluated. Perhaps most important in the evaluation is the medical history, fol-lowed by understanding whether physical issues such as pressure, cold, and scratch-ing affect the skin. These issues must be carefully explored in the initial questioning of the patient.

Certain types of urticaria may be brought on by physical disruption of mast cells by either cold, scratching, or pressure. There is no IgE mediation of these reac-tions, unlike those from foods, but hista-mine release from the cells is common to all. Swelling of the skin due to damage to small blood vessels causes burning and pain of the areas involved and may last for several days. The burning and pain are unrelated to allergies or physical mast cell disruption. These might typically be related to a systemic disorder, and precipitating

Box 9.1 Types of Urticaria

IgG autoantibodies against C1q may be found along with other organ involvement. Fevers, bone pain, and arthralgia may also occur along with the skin involvement.

Swelling of the skin without wheals, or angioedema, may be due to C1 esterase inhibitor deficiency, and this may be a hereditary or an acquired disease. The reac-tions may be painful subcutaneous or sub-mucosal reactions initiated by trauma and may involve the gut, causing colic, or the larynx, causing difficulty breathing. This type of angioedema is rare but potentially life threatening.

Case 9.3 Atopic Dermatitis

J.E. is a nineteen-year-old male with a family history of allergies who devel-oped severe pruritis, which is usually worse at night. As a toddler, he had aller-gic reactions to milk and eggs, which resolved by age 4. In addition, he was a mild asthmatic until puberty. In his mid-teens, he developed a pruritic, crusty rash, which was relieved by cortico-steroid creams and antihistamines and resolved somewhat during the summer months, where he lived near the ocean.

After switching to cotton sheets and eliminating his wool blanket, he improved slightly and was finally

evaluated by an allergist. Prick skin tests revealed a significant reaction to dermatophagoides farinae or dust mite, and subsequently, he covered the sheets, mattress, box spring, and pil-lows with sealable covers of less than 2 µ of mesh. He also used a mild cortico-steroid cream; the scratching stopped, and his skin cleared up.

Case 9.4 Atopic Eczema

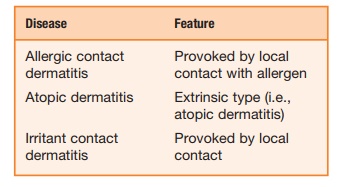

Atopic eczema is an inflammatory skin disease characterized by severe pruritis with a chronic, relapsing course. Acute eczema is associated with marked erythema, superficial papulae, and vesiculae, which easily excoriate leading to crusting. It is the most com-mon dermatologic problem for which a dermatologist is consulted. The IgE level in most people with atopic eczema is elevated and is specific to foods and environmental allergens.

Provocative factors of atopic eczema are varied and may include stress, skin irritants, food allergens, environmen-tal allergens, climate, season, and hor-mones. Avoiding the suspected foods has a mixed response. Often food restric-tion during a child’s early life leaves the child open to detrimental psychological and growth issues during those impor-tant developmental years. Fortunately, many food allergies tend to resolve over time; however, in the beginning of avoidance techniques, careful evalu-ation is mandatory. In addition, exces-sive amounts of certain foods such as citrus in children and alcohol in adults make eczema worse, and these reactions may be unrelated to an IgE-mediated problem. It seems that food allergy and the intolerance (non-IgE mediated) are important factors in atopic dermatitis.

Box 9.2 Classification of Common Eczematous Skin Diseases

Although those with atopic eczema often test positive to various foods and house dust mites, strict avoidance of these allergens does not improve the problem. Although allergies are an important component in atopic eczema, an esti-mated 90 percent of patients with moder-ate to severe eczema have staphylococcal infection of the skin. This condition and large insensible water loss make atopic eczema a difficult medical problem.

The effects of the weather, including temperature and humidity, on eczema add to these immunological and nonim-munological factors. A day at the beach may have a positive effect on atopic dermatitis, while a dry, cold winter has the opposite effect. Wet wraps are ben-eficial because they replace the skin’s moisture loss. Corticosteroid creams, hydrotic creams and ointments, and occasional oral antibiotics are the main-stays of treatment. Avoiding allergens, local skin care, and treatment of the pru-ritis are the best approaches for treating atopic eczema

Atopic Keratoconjunctivitis

Conjunctivitis is an inflammation of the conjunctiva, the inner eyelid surfaces and the mucous membrane lining the sclera. When the cause is seasonal or perennial (very common), the etiology may be pollen, animals, or dust mites. Prevalence is com-mon, and the treatment usually involves mast cell inhibitors and topical and systemic antihistamines. Topical ophthalmic steroids are usually avoided.

Atopic keratoconjunctivitis is a rare, lifelong problem, seen more commonly in adults with atopic disease such as atopic dermatitis. This facial eczema usually involves the eyelids, and the lid margins usually show chronic inflammation of the lash follicles (blepharitis) and staphylococ-cal organisms. In addition, the lid margins may thicken and keratonize, and the lids may turn out or turn in. Corneal plaques, cataracts, and defects of the corneal epithe-lial may lead to loss of sight.

Topical mast cell stabilizers may be used for atopic keratoconjunctivitis, but often topical corticosteroids are required. Facial eczema must be controlled, and the lid margins must be treated. Conventional treatment for seasonal or perennial allergic conjunctivitis is not sufficient. Atopic kera-toconjunctivitis may be difficult to manage.

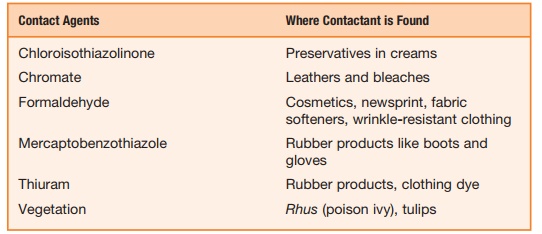

Case 9.4 History Contact Dermatitis

A.A. is a fifty-six-year-old woman who decided, after many years of pro-crastination, to have her ears pierced. Within four to six weeks of the proce-dure, she developed protracted pruritis (itchiness) at the site of the piercing, with a crusty rash. She then found she could no longer wear her wedding band or bracelets because of similar reactions.

Patch testing to various allergens, including nickel, was performed. She had a severe forty-eight-hour reaction to nickel, a metal used in jewelry to harden the gold or silver. A.A. could no longer wear her earrings, rings, or bracelets. She could only wear 24-karat gold or .999 fine silver.

Box 9.3 Where Contact Agents are Found

Contact Dermatitis

Classical contact dermatitis is a Gell and Coombs type IV reaction, mediated by previously sensitized lymphocytes, which is exhibited by raised, very pruritic rash at the sight of the contact. Unlike allergic reactions of a type I, IgE-mediated contact dermatitis, as a type IV reaction, involving low-molecular-weight allergens (less than 1 kDa). These contact allergens are haptens and need to link with proteins in the skin to become allergenic. These haptens may be readily absorbed into the skin, a reac-tion that renders them antigenic. If the skin is exposed to humidity or warmth, the penetration of the hapten is greater, and the chance of developing contact dermatitis is greater. As these haptens make their way into extravascular spaces, they combine with serum proteins or cell membranes of antigen-presenting cells. The processed antigens is presented by Langerhans cells to T cells leading to a cascade of events that result in an influx of mononuclear cells into the dermis and epidermis, hence dermatitis.

Although most people exposed to these presenting allergens do not develop contact dermatitis, certain substances such as dinitrochlorobezene may sensitize as many as 90 percent of normal individuals, which is why the patient’s history with suspected contact dermatitis is impor-tant. Among those situations patients need to elucidate are occupation, cosmet-ics, topical or systemic drugs, recreational activities, effects of holidays, and time course.

Testing for contact dermatitis involves placing a patch of the suspected substance or substances on the back. The area must be kept clean and dry for forty-eight hours, after which the various patches are removed, and the individual areas are evaluated for inflammatory responses. A positive response then characterizes a type IV reaction, and avoidance of the offending allergen is the treatment of choice. Thirty milligrams per day of systemic steroids may be required when large areas of the skin are involved (>25 percent of body surface). Otherwise, corticosteroid creams may be employed; however, avoidance of the contactant is most crucial.

Related Topics