Chapter: Obstetrics and Gynecology: Sexual Assault and Domestic Violence

Sexual Assault

SEXUAL ASSAULT

Sexual

assault is defined legally as involving any genital, oral, or anal penetration

by a part of the accused’s body or by an object, using force or without

consent. Criminal sexual assault, orrape, often is further

characterized to include acquaintance rape, date rape, “statutory rape,” child

sexual abuse, and in-cest. These terms generally relate to the age of the

victim and her relationship to the abuser.

Each year, some 365,000 women in

the United States experience sexual assault, rape, or attempted rape. An

es-timated 1 in 6 women have experienced sexual assault in their lifetimes.

However, most do not file a complaint or report and, thus, its true prevalence

is unknown. In the years between 1992 and 2000, 63% percent of completed rapes,

65% of attempted rapes, and 74% of completed and attempted sexual assaults

against females were not re-ported to the police. Because of the complex

problems caused by sexual assault, treatment is best managed by a

multidisciplinary team that fulfills the following roles:

·

Care for

the victim’s emotional needs, acute and (ifpossible within the

constraints of the healthcare system) long-term

·

Evaluation

and treatment of medical needs, acuteand follow-up

·

Collection

of forensic specimens and preparation of arecord

acceptable for healthcare and in the legal process

Definitions and Types of Sexual Assault

Sexual assault occurs in all age,

racial, and socioeconomic groups; the very young, handicapped, and the very old

are particularly susceptible. Although the act may be com-mitted by a stranger,

in many cases it is committed by an acquaintance.

Some situations have been defined

as variants of sexual assault. Marital

rape is defined as forced coitus or related sexual acts within a marital

relationship without the consent of a partner; it often occurs in conjunction

with and as part of physical abuse in cases of domestic or intimate-partner

violence.

Date rape

or

acquaintance rape is another manifes-tation of intimate-partner violence.

In this situation, a woman may voluntarily participate in sexual play, but

coitus occurs, often forcibly, without her consent. Date rape often goes

unreported, because the woman may think that she contributed to the act by

participating up to a point or that she will not be believed. Lack of consent

also may occur in situations where cognitive function is im-paired by

flunitrazepam, alcohol, or other drugs; sleep; in-jury with unconsciousness; or

developmental delay.

All states have statutory rape

statutes criminalizing sexual intercourse with a girl younger than a specific

age, because she is defined, by statute, as being incapable of consenting. Many

states also have laws addressing aggra-vated

criminal sexual assault, which has the following attributes: weapons are

used, lives are endangered, or phys-ical violence is inflicted; the act is

committed in relation-ship to another felony; or the woman is older than 60

years, physically handicapped, or mentally retarded.

Management

The medical and health consequences of sexual assault are both short- and long-term. Clinicians should be aware that their practices will include women with a history of sexual assault, and they should be familiar with both the short- and long-term sequelae. All patients should be screened for a history of sexual assault. Most women with a history of sexual assault will not have reported it to a nonpsychiatric physician. Yet, women with a history of assault are more likely to present with chronic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, menstrual cycle disturbances, and sexual dysfunction than are women without such a history.

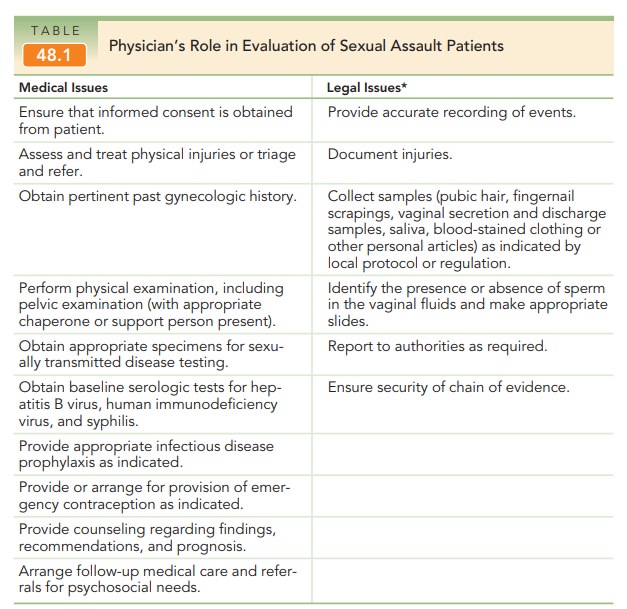

Clinicians evaluating women in

the acute phase who have experienced sexual assault have a number of

responsi-bilities, both medical and legal (Table 48.1). They should be familiar

with state rape and assault laws, and comply with any legal requirements

regarding reporting and the collec-tion of evidence. They also must be aware

that every state and the District of Columbia require physicians to report

child abuse, including sexual assault against children and adolescents.

Physicians should be familiar with any state laws regarding the reporting of

statutory rape. Additionally, physicians should be aware of local protocols

regarding the use of specially trained sexual assault forensic examiners or

sexual assault nurse examiners. Specific responsibilities are determined by the

patient’s needs and by state law.

The clinician should provide

medical and counseling services, inform the patient of her rights, refer her to

legal assistance, and help her develop prevention strategies to avoid future

assault. Many jurisdictions and several clinics have developed a sexual assault

assessment kit, which lists the steps necessary and the items to be obtained so

that as much information as possible can be prepared for forensic purposes.

Many clinics have nurses who are trained to col-lect needed samples and

information. If these individuals are available, it is appropriate to request

their assistance. Rape crisis counselors and centers also can provide valuable

support. In addition, the clinician must assess and treat all injuries, perform

sexually transmitted disease (STD) screen-ing, and provide prophylaxis against

infectious diseases and unintended pregnancy.

INITIAL CARE

When a

woman who has experienced sexual assault communicates with the physician’s

office, emergency room, or clinic before pre-senting for evaluation, she should

be encouraged to come immedi-ately to a medical facility and be advised not to

bathe, douche, urinate, defecate, wash out her mouth, clean her fingernails,

smoke, eat, or drink.

In recent years, there has been a

trend toward the im-plementation of hospital-based programs to provide acute

medical and evidentiary examinations by sexual assault nurse examiners or

sexual assault forensic examiners. Physi-cians play a role in the policy and

procedure development and implementation of these programs, and serve as

sources for referral, consultation, and follow-up. In some parts of the

country, however, obstetrician–gynecologists will still be the first point of

contact for evaluation and care in the acute aftermath of a sexual assault. In

addition, virtually all obstetrician–gynecologists will be called on to perform

evaluations and, if conducting screening for history of sex-ual assault, will

realize the utility of this information to the conduct of primary-care and

specialty-care practice.

In an optimal situation, the

woman is able to seek care in a facility where there is a trained

multidisciplinary team. A team member should remain with the patient to help

provide a sense of safety and security and, thereby, begin the therapeutic

process, including, specifically, assurance of the patient’s lack of guilt. The patient should be encouraged,in a

supportive, nonjudgmental manner, to talk about the assault and her feelings. Treatment

for life-threatening traumaneeds to begin immediately. Such trauma is uncommon,

although minor trauma is seen in one-fourth of victims. Even in life-threatening

situations, any sense of control that can be given the patient is helpful.

Obtaining consent for treatment is not only a legal requirement, but also an

important aspect of the emotional care of the patient, by helping her

participate in regaining control of her body and her circumstances.

Although patients are commonly

reluctant to do so, they should be gently encouraged to work with the police,

because such cooperation is clearly associated with im-proved emotional

outcomes for victims.

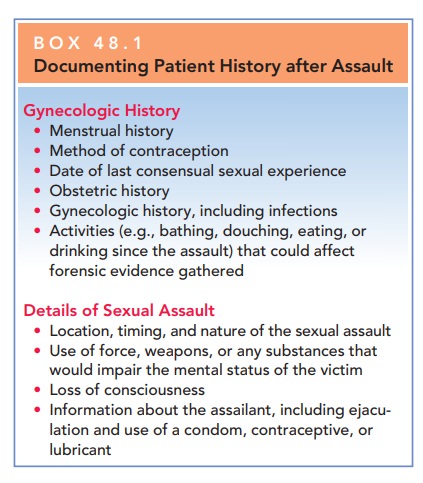

History taking about a sexual

assault is necessary to gain medical and forensic information, and is as well

an important therapeutic activity. Recalling the details of the assault in the

supportive environment of the healthcare setting allows the victim to begin to

gain an understand-ing of what has happened and to start emotional healing (see

Box 48.1.).

Box 48.1

Documenting Patient History after Assault

Gynecologic History

Menstrual history

Method of contraception

Date of last consensual sexual experience

Obstetric history

Gynecologic history, including infections

Activities (e.g., bathing, douching, eating, or drinking since the assault) that could affect forensic evidence gathered

Details of Sexual Assault

Location, timing, and nature of the sexual assault

Use of force, weapons, or any substances that would impair the mental status of the victim

Loss of consciousness

Information about the assailant, including ejacu-lation and use of a condom, contraceptive, or lubricant

Victims of sexual assault should

be given a complete general physical examination, including a pelvic

examina-tion. Forensic specimens should be collected, and cultures for STDs

should be obtained. When collecting forensic specimens, it is critical that the

clinician follow the direc-tions on the forensic specimens kit. These specimens

are kept in a health professional’s possession or control until turned over to

an appropriate legal representative. This “protective custody” of the specimens

ensures that the correct specimen reaches the forensic laboratory and is called

the “chain of evidence.”

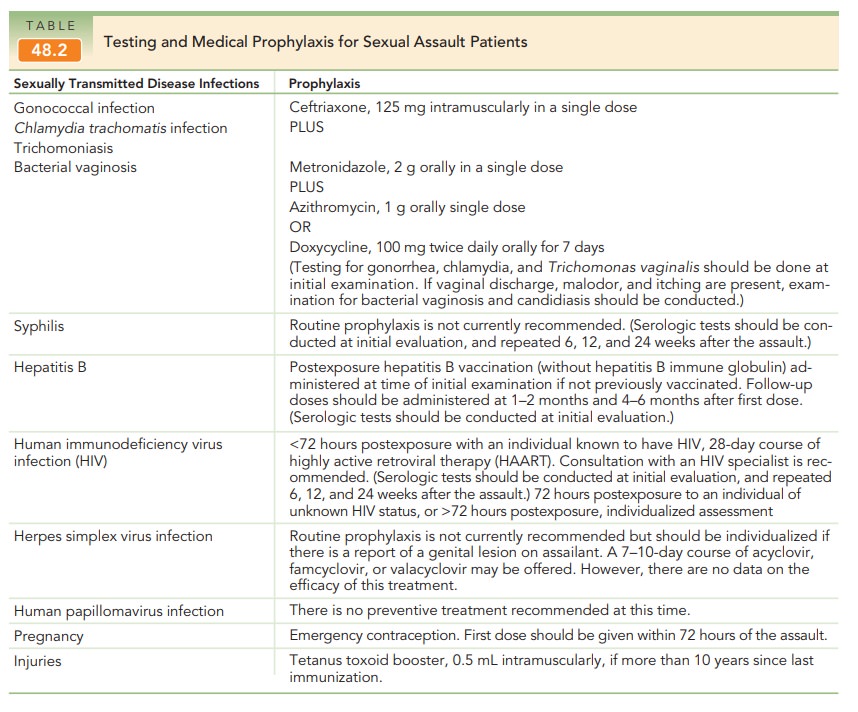

Initial laboratory tests should

include cultures from the vagina, anus, and pharynx for STDs. Collection of

serum for rapid plasma reagin (RPR) for syphilis, hepati-tis antigens, and

human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are needed. Urinalysis, culture and

sensitivity, as well as a pregnancy test for menstrual-age women (regardless of

contraceptive status) are collected. Antibiotic

prophy-laxis should be offered to all adult patients. Emergency contraception should be offered and is described on

contraception (see Table 48.2).

Within 24

to 48 hours of disclosure and initial treatment, victims should be contacted by

phone or seen for an immediate post-treatment

evaluation. At this time, emotional or physi-cal problems are

managed and follow-up appointments arranged. Potentially serious problems, such

as suicidal ideation, rectal bleeding, or evidence of pelvic infection, may go

unrecognized by the victim during this time because of fear or continued

cognitive dysfunction. Specific questions must be asked to ensure that such

problems have not arisen.

SUBSEQUENT CARE

At the 1-week follow-up visit, a

general review of the pa-tient’s progress is made and any specific new problems

ad

The next routine visit

is at 6 weeks, when a com-plete evaluation, including physical examination,

repeat cultures for sexually transmitted diseases, and a repeat RPR is

performed. Another visit at 12 to 18 weeks may be indicated for repeat HIV

titers, although the current un-derstanding of HIV infection does not allow an

estimate of the risk of exposure for sexual assault victims. Each vic-tim

should receive as much counseling and support as is necessary, with referral to

a long-term counseling pro-gram if needed.

If the physician is not directly

involved in the acute care of the victim, it is helpful for him or her to

obtain records of the patient’s emergency evaluation. These enable the

physician to be certain that all appropriate testing was per-formed and to

provide the patient with full results. Patients may be disturbed to learn that

the results of their forensic evaluation are usually not provided to their

physician. In this situation, it is helpful to refer the patient to local legal

or police authorities, who can also be helpful in answering patients’ questions

about the health status of the assailant and whether the assailant was

apprehended.

Emotional Issues

A woman who is sexually assaulted

loses control over her life during the period of the assault. Her integrity,

and sometimes her life, is threatened. She may experience in-tense anxiety,

anger, or fear. After the assault, a “rape-trauma” syndrome commonly occurs,

comprising two phases:

ACUTE PHASE (IMMEDIATE RESPONSE)

·

May last for hours or days

·

Characterized by distortion or

paralysis of the individ-ual’s coping mechanisms

·

Outward responses vary from

complete loss of emo-tional control to an apparently well-controlled behavior

pattern.

·

Signs may include generalized

pain throughout the body; headache; eating and sleep disturbances; and

emotional symptoms, such as depression, anxiety, and mood swings.

DELAYED (OR ORGANIZATION) PHASE

·

Characterized by flashbacks,

nightmares, and phobias as well as somatic and gynecologic symptoms

·

Often occurs months or years

after the event, and may involve major life adjustments

This rape-trauma syndrome is

similar to a grief reaction in many respects. As such, it can only be resolved

when the victim has emotionally worked through the trauma and personal loss

related to the event and replaced it with other life experiences. An inability to think clearly or

rememberthings such as her past medical history, termed “cognitive dys-function,” is a particularly distressing aspect of

the syndrome.The involuntary loss of cognition may raise fears of “being

crazy” or of being perceived as “crazy” by others. It is also frustrating for

the healthcare team, unless it is recognized that this is an involuntary,

temporary, and understandable reaction to the emotionally intolerable nature of

the sexual assault and not a willful action.

Those who have experienced

physical and sexual as-sault also are at great risk of developing posttraumatic

stress disorder. Clusters of symptoms may not appear for months or even years

after a traumatic experience. These clusters are typical symptom categories

associated with posttraumatic stress disorder, including:

·

Reliving the event

·

Experiencing flashbacks,

recurring nightmares, and, more specifically, intrusive images that appear at

any time

· Extreme

emotional or physical reactions, including shak-ing, chills, palpitations, or

panic reactions, often accom-pany vivid recollections of the attack.

Avoiding

reminders of the event constitutes another symp-tom cluster in posttraumatic

stress disorder. These women become emotionally numb, withdrawing from friends

and family and losing interest in everyday activities. There may be an even

deeper reaction of denial of awareness that the event actually happened.

Symptoms such as easy startling, being hypervigilant, irritability, sleep disturbances, and lack of concentration are part of a third symptom cluster known as hyper-arousal. These women often will have a number of co-occurring conditions, such as depression, dissociative disorders (los-ing conscious awareness of the present, or “zoning out”), addictive disorders, and many physical symptoms.

Related Topics