Chapter: Obstetrics and Gynecology: Sexual Assault and Domestic Violence

Domestic Sexual Violence

DOMESTIC VIOLENCE

Domestic violence is reported by

over 25% of women at some time during their lives and is a significant source

of illness and injury to women.

Definition

Domestic

violence refers to violence perpetrated withinthe context of

family or intimate relationships. Family members include parents, siblings, and

other blood rela-tives, as well as legal relatives such as stepparents,

in-laws, and guardians. Violence that occurs between current or for-mer

partners is referred to as intimate-partner

violence and includes male abuse by female partners and violence be-tween

partners in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered relationships.

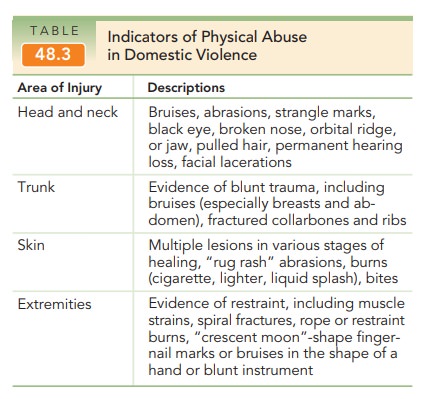

Domestic violence may involve one or more of three pre-sentations. Physical abusesuch as hitting, slapping, kick-ing, and choking, is the most obvious presentation. It is suspected with evidence of trauma, especially to the head and neck or trunk associated with a history of violence, or when an explanation of the trauma doesn’t seem appro-priate (Table 48.3). Unfortunately, pregnancy appears to be a period of greater risk for such episodes. Sexual abuse is another presentation of domestic violence. The third pre-sentation is emotional, financial, or psychological abuse,neglect, or threat, and is often traumatic and/or long-standing. Examples include undermining of self-worth, deprivation of sleep or emotional support, repetitive un-predictability of response to life situations, threats, de-struction of personal property or the killing of pets, lies, manipulation of friends, and interference in the work-place. Domestic violence is usually cyclic and repetitive, with periods of calm alternating with periods of rapidly increasing tensions or violence, the latter often increasing in severity with each iteration of the cycle.

Screening: Risk Factors

Recognition

is the first, most important, and most often a missed issue. When

domestic violence is suspected, compassionateand thoughtful discussion with the

possible victim, as well as attention to any physical injury, is requisite. All

patients should be asked about violence in their lives as part of the routine

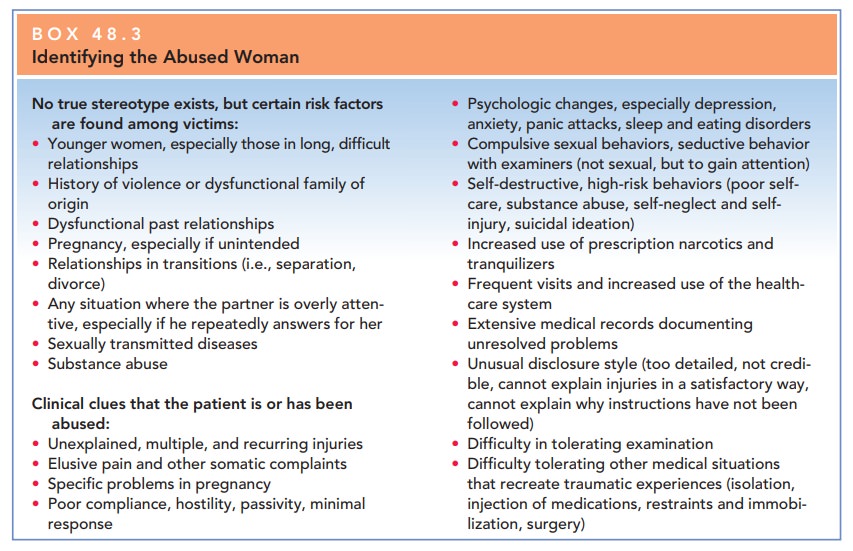

health history. Although all women are at risk for abuse, certain life

experiences and circumstances may place some women at greater risk (Box 48.3).

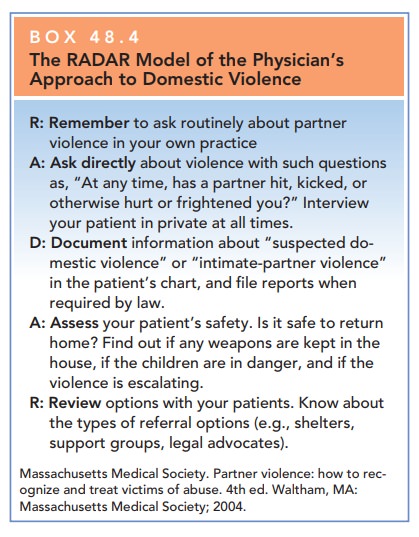

The clinician’s role is 1) to

know the signs and symp-toms of intimate-partner violence, 2) to ask all

patients about past or present exposure to violence, 3) to intervene and refer

as appropriate, and 4) to assess the patient’s risk of danger (Box 48.4).

Counseling

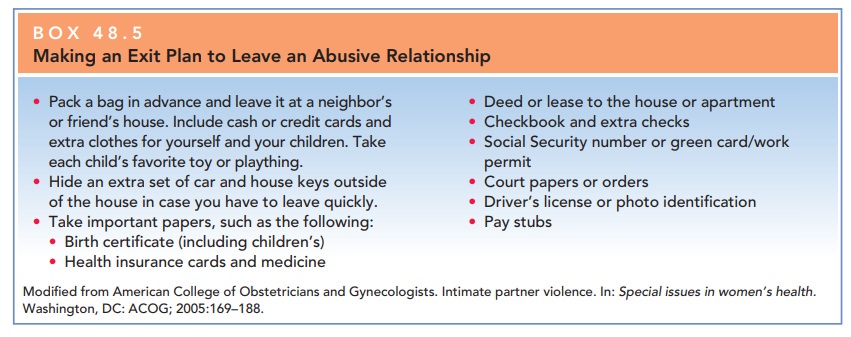

If the patient will be returning

to an unsafe home, safety planning should be conducted, and referrals to

service agencies in the community should be provided. Women can be encouraged

to call a woman’s shelter for more help

Box 48.4

The RADAR Model of the Physician’s Approach to Domestic Violence

Remember to ask routinely about partner

violence

in your own practice

Ask directly about violence with such questions as, “At any time, has a

partner hit, kicked, or otherwise hurt or frightened you?” Interview your

patient in private at all times.

Document information about “suspected do-mestic violence” or

“intimate-partner violence” in the patient’s chart, and file reports when

required by law.

Assess your patient’s safety. Is it safe to return home? Find out if any

weapons are kept in the house, if the children are in danger, and if the violence

is escalating.

Review options with your patients. Know about the types of referral options (e.g., shelters, support groups, legal advocates).

Related Topics