Chapter: Obstetrics and Gynecology: Sexual Assault and Domestic Violence

Child Sexual Assault

CHILD SEXUAL ASSAULT

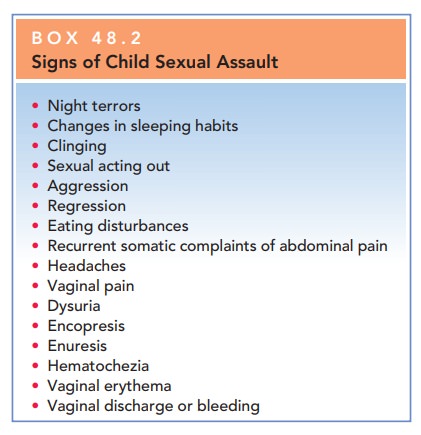

Ninety percent (90%) of child victimization is by par-ents, family members, or family friends; “stranger rape” is relatively uncommon in children. It is extremely impor-tant to know who the perpetrator is and how the child sus-tained the injury, so that the child can be removed from an unsafe environment. Box 48.2 shows behavioral and physical signs and symptoms commonly associated with child sexual abuse.

Assessment/Examination

Because the assessment of a child for sexual abuse involves specific skills and has the potential for legal challenge, the individual who undertakes this evaluation should have sig-nificant experience in this area.

This assessment

usually is done by pediatricians and is beyond the skills of most general

gynecologists. Awareness of and sensitivity to the issues, special needs, and

circumstances of the child are important for obstetrician–gynecologists who are

consulted to treat an injury to the pelvic floor. In many cities, a child abuse

team consisting of trained experts and including physicians, social workers,

and counselors is available to perform the assessment.

The sexual abuse evaluation

begins with an interview of the caretaker and the child. Unless the child

refuses to leave the caretaker, the child should be interviewed pri-vately to

obtain specific details of the abuse. Questioning should be nondirect to elicit

spontaneous responses such as time and location of the abuse, description of

the scene, name and description of the perpetrator, and type of sex-ual acts.

The child’s statements should be recorded verba-tim; electronic interviews are

helpful so that the child does not have to describe the abuse repeatedly. Good

docu-mentation of the interview is critical in the prosecution of sexual abuse

cases because, in many instances, the patient’s statement is the only evidence

that the abuse occurred. Documentation of the specific names the child uses for

her genitalia is recommended to help others understand the context of her

statements.

The urgency of an evaluation of sexual abuse depends on how soon after the event the child is brought in for care. If the child presents within 72 hours of the last episode of abuse, the physician should immediately arrange for eval-uation of the child and focus on collection of forensic evi-dence. However, fewer than 10% of child sexual abuse cases are reported within 72 hours. In cases that are re-ported after 72 hours, the patient should be referred to the nearest sexual abuse center, where more resources are available to conduct the evaluation.

MANAGEMENT

In the treatment of a child who

is the victim of sexual abuse, management should focus (as applicable) on

repair of injuries, treatment of STDs, prevention of pregnancy, protection

against further abuse, and psychologic support for the patient and her family.

Superficial injuries (e.g., bruises, edema, local irritation) resolve within a

few days and require only meticulous perineal hygiene. In some patients with

extensive skin abrasions, broad-spectrum antibiotics should be given as

prophylaxis. Small vulvar hematomas usually can be controlled by pressure with

an ice pack, and even massive swelling of the vulva usually subsides promptly

when cold packs and external pressure are applied. Injuries to the vagina or

rectum may present surgical difficulties because of the small size of the

organs involved. More extensive penetrative vaginal and anal injuries require

thorough radiographic and anesthetic examination to rule out intraabdominal

penetration.

Related Topics