Chapter: Obstetrics and Gynecology: Human Sexuality

Management of Human Sexuality

MANAGEMENT

A woman’s sexuality is influenced

by her health and emotional well-being; likewise, healthy sexual function-ing

promotes physical and emotional well-being. How-ever, studies suggest that

fewer than one-half of patients’ sexual concerns are recognized by their

physicians. The

obstetrician-gynecologist has a

paramount role in assessing sexual function and managing sexual dysfunc-tion to

ensure the well-being of his or her patients. Beginning with screening a

patient for sexual dysfunc-tion, taking her history, and assessing sexual

dysfunction risk factors, the physician establishes a diagnosis if dys-function

is present and treats the patient or refers her for treatment, as appropriate.

Screening for Sexual Dysfunction

Questioning patients about their sexual desire, especially about responsive desire and the components of arousal, can point to management options about which patients and their partners can be counseled.

Simply providing infor-mation, confirming that many women have the same

con-cerns, and explaining how one aspect of dysfunction leads to another can be

therapeutic.

Discussions of sexuality are accomplished

best in a confidential and supportive setting. Mutual trust and respect in the

patient–clinician relationship will allow appropriate discussion of questions

and concerns about sexuality. A nonjudgmental and respectful approach by the

clinician, as well as awareness by the clinician of his or her own biases, is

essential for effective care.

Patients are more likely to develop trusting rela-tionships with their healthcare practitioners when the issue of confidentiality has been addressed directly.

A confidential relationship, in

turn, can facilitate the open disclosure of health histories and behaviors. The

use of broad, open-ended questions in a routine history gath-ering can help

disclose problems that require further exploration. Inquiry about the partner’s

sexual function and level of satisfaction may elicit more specific infor-mation

and give an indication of the couple’s level of communication.

The following are examples of

basic questions, posed in a gender-neutral fashion:

“Are you sexually active?”

“Are you sexually satisfied?”

“Do you think your partner is

satisfied?”

“Do you have questions or concerns

about sexual func-tioning?”

The clinician should not make

assumptions about the woman’s choice of partner. Although most women report

that their sexual partners are men, some women only have sex with other women,

and others may have partners of both sexes. The use of terms such as partner instead of husband and sexual activity

instead of intercourse and an

understand-ing of nonheterosexual sexuality—including that of les-bians,

bisexual women, and transgendered individuals— will assist in open communication

and assessment of the patient’s problem.

History

The patient’s history is the

crucial part of an assessment for sexual dysfunction. The duration of the

dysfunction and how long it has evolved over months or years should be clar-ified.

Lifelong problems are particularly difficult to evaluate and manage, and a

concomitant in-depth psychological assessment may be needed. The context of the

patient’s life when the dysfunction began is needed, addressing psycho-logic,

biologic, and relationship factors. Her medical history and past sexual

experiences are recorded, including med-ications and any substance abuse. The

woman’s develop-mental history also may be needed, particularly if her

dysfunction is lifelong.

Deliberate inquiries should be

made to assess the quality of the interpersonal relationship between the

patient and her partner, including mutual satisfaction with their sexual

relationship. The perceived impor-tance of physical intimacy for a given couple

depends largely on whether or not they are satisfied with that aspect of their

relationship. Among couples who are not experiencing sexual dysfunctions, each

partner will esti-mate that the sexual component of their relationship accounts

for approximately 10% of their overall happi-ness. In couples experiencing

sexual difficulties, however, the sexual aspects are estimated as accounting

for approx-imately 60% of the overall relationship quality. This dra-matic

shift in perception underscores the importance that physical intimacy holds

within the context of the over-all relationship.

Risk Factors

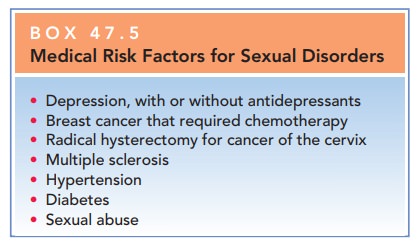

Sexual disorders often are

disclosed by women during vis-its for routine gynecologic care. Some patients

present with a complaint involving a sexual issue or of a specific sexual

dysfunction. Other patients neither express a sexu-ally related complaint nor

have a medical problem with a commonly associated sexual issue. Still other

patients have a medical problem or have or have had a medical or surgi-cal

therapy that is known to be associated with sexual issues or problems (Box

47.5).

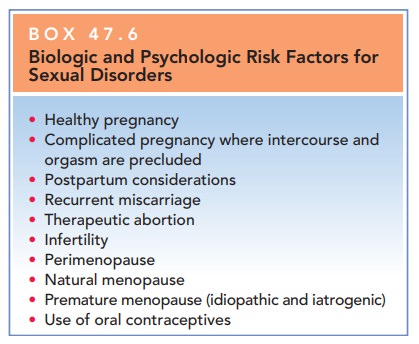

In addition, sexual function may

be affected by bio-logic and psychologic aspects of reproduction and the life

cycle (Box 47.6). The mechanisms governing the interplay

Box 47.5

Medical Risk Factors for Sexual Disorders

Depression, with or without antidepressants

Breast cancer that required chemotherapy

Radical hysterectomy for cancer of the cervix

Multiple sclerosis

Hypertension

Diabetes

Sexual

abuse

Box 47.6

Biologic and Psychologic Risk Factors for Sexual Disorders

Healthy pregnancy

Complicated pregnancy where intercourse and orgasm are precluded

Postpartum considerations

Recurrent miscarriage

Therapeutic abortion

Infertility

Perimenopause

Natural menopause

Premature menopause (idiopathic and iatrogenic)

Use of oral contraceptives

However, women’s past sexual experiences, self-image, support

from and attraction to their sexual partners, suffi-ciency of their knowledge

of sexuality, and sense of con-trol are all typically important factors.

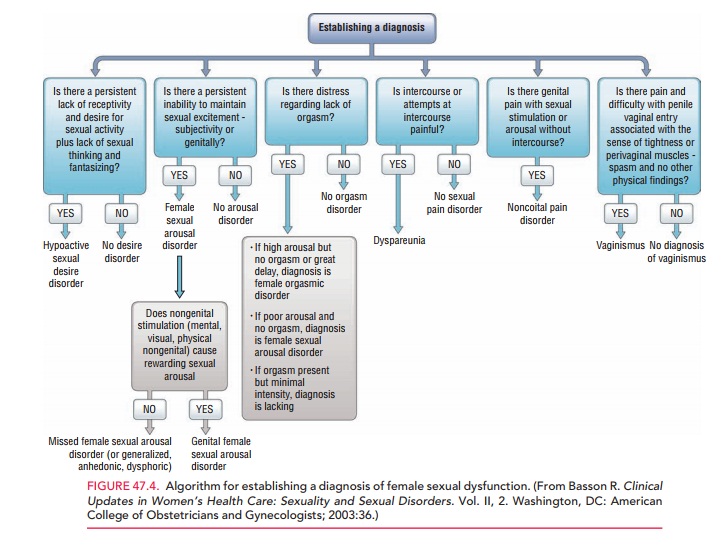

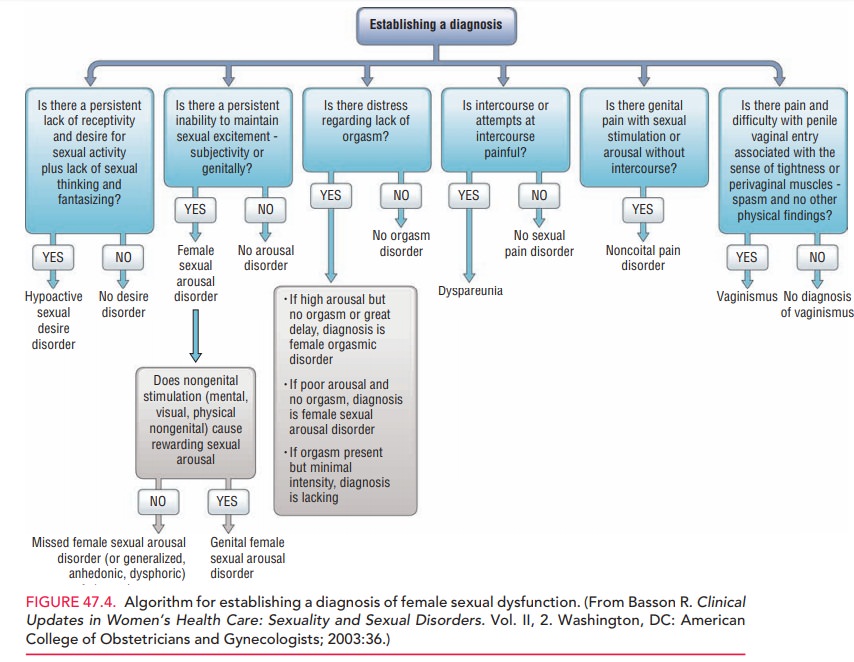

Establishing a Diagnosis

For all of the various

dysfunctions, it is important to estab-lish whether it is lifelong or acquired

and to distinguish between dysfunctions that are situational and those that are

global or generalized (Fig. 47.4). If the woman’s sex-ual response is healthy

in some circumstances, physical organic factors are not involved in a

dysfunction. It is therefore important to ask patients about their sexual

response with masturbation, with viewing or reading erot-ica, and with being

with individuals other than their regu-lar partners—even if this activity does

not involve physical sexual interaction.

Treatment

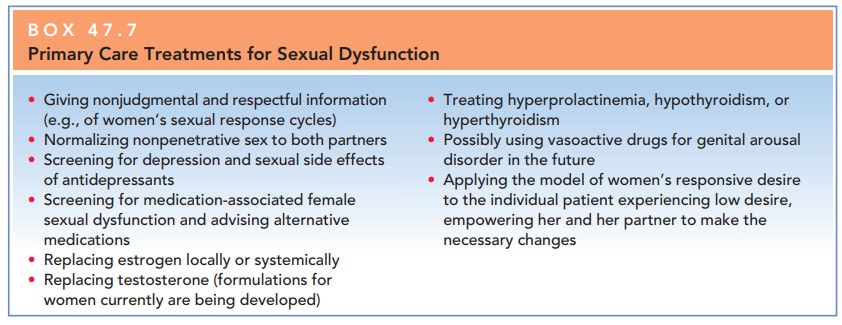

Some sexual problems can be managed by the primary physi-cian, whereas others are best referred to a sex therapist. Adetailed, sensitive, and respectful assessment will help establish a dialogue with the patient. It is difficult to dis-tinguish between assessment and treatment, because the physician often provides information during the assess-ment that is therapeutic. Treatment may be within the scope of the obstetrician-gynecologic practice, or a refer-ral may be appropriate, depending on the nature and the extent of the problem. Box 47.7 shows interventions that commonly occur in gynecologic offices.

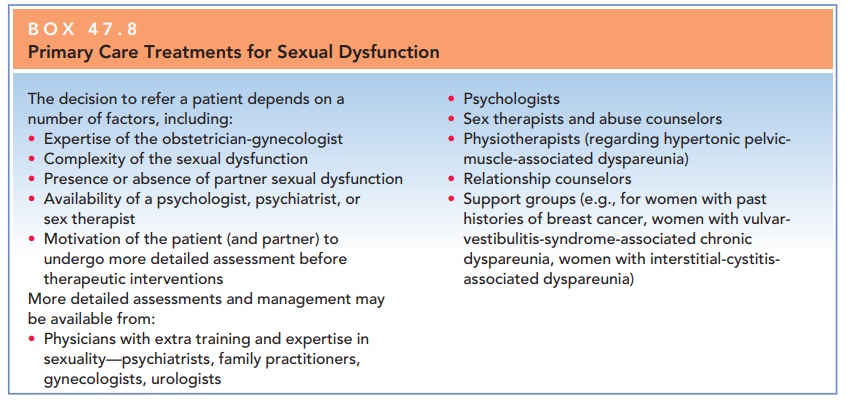

Largely, the decision should be based on whether or not the physician has adequate resources to

approach sexual dysfunction from an integrated perspective, rather than merely

a biological one. Psychology, pharmacology, partner inti-macy, and alternative

therapies are some of the other factors that must be addressed in treating

sexual dys-function. Referrals to mental health practitioners, marriage or

relationship counselors, or sex therapists may be appropriate. Box 47.8 shows

when and why to refer patients.

Related Topics