Chapter: Aquaculture Principles and Practices: Oysters and Mussels

Production of seed oysters

Production of seed oysters

As stated earlier, most present-day production of oysters is from collected wild spat. Methods for hatchery production of seed oysters have been developed and are being practised on a commercial scale by a small number of producers. Though the value of and need for hatchery-produced seed oysters are well recognized, it would appear that production costs have stood in the way of wider application of this technique. Oyster larvae normally settle in sites with low current velocities, but these areas may not be rich in plankton and so may not be conducive to good growth rates. As spat-fall often occurs in areas away from environments suitable for oyster growing, the collection, transport and sale of oyster spat has developed into a separate industry. Similarly, hatchery production of seed oysters is a separate specialized activity, and oyster farmers often start their operations with purchased seed. Countries like Japan export large quantities of seed oysters to other oyster-growing countries.

There is considerable variation in the time and abundance of spat-fall in any area, depending on a number of environmental factors including temperature and salinity. For successful spat collection, suitable collecting devices have to be set in the proper place at the proper level and time. Even though spat may settle at a wide range of depths, their survival is greatest in the intertidal zone, relatively safe from predators. Early setting of the spat collectors will result in the substrate becoming covered with fouling organisms, whereas late setting may result in poor collection of spat. Regular examination of plankton in the area will help to determine the actual time and place of spat-fall. Generally, spawning occurs at temperatures of 15–20°C in summer and autumn, but tropical species spawn throughout the year at higher temperatures.

As well as the time and place of spat collection, the type of spat collector used is also of importance. As mentioned earlier, different types of collectors are in use, and they may be placed on the bottom or on raised structures. Though the main criteria in selecting the type of collector are easy availability, ease of handling and the surface area offered for the attachment of spat, the larvae of some species appear to exhibit preferences for certain types of substrates. For example, the European oyster seems to have a preference for materials containing calcium carbonate, whereas the American oyster may settle on any hard surface, including wood, plastic or glass. It has been reported that shells treated with highly chlorinated benzenes, such as polystream, collected about two or three times as many oyster spat as untreated ones, and fouling and drilling of young oysters were significantly reduced (MacKenzie et al., 1961). Though Castagna et al. (1969) reported the commercial feasibility of using treated collectors, this practice does not appear to have been widely employed.

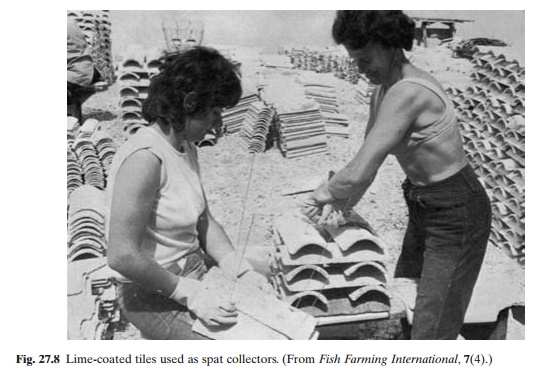

Collectors used in France and some other European countries for the European flat oyster and the Portuguese oyster generally consist of semi-cylindrical ceramic roof tiles (10–12cm in diameter and 30 cm long), stacked in pairs (fig. 27.8). The tiles are coated with lime and this facilitates the subsequent removal of spat which have settled on the tiles. Each stack of three to six pairs is tied together for easy handling and placed on wooden platforms, at least 15–30 cm above the bottom. Collectors for Portuguese oyster spat can be placed nearer to the shore, as they can tolerate higher temperatures and exposure to the sun at low tides. InItaly and the former Yugoslavia, oyster farmers sometimes use branches of trees or bushes such as juniper as spat collectors and they are suspended from ropes in the littoral areas.

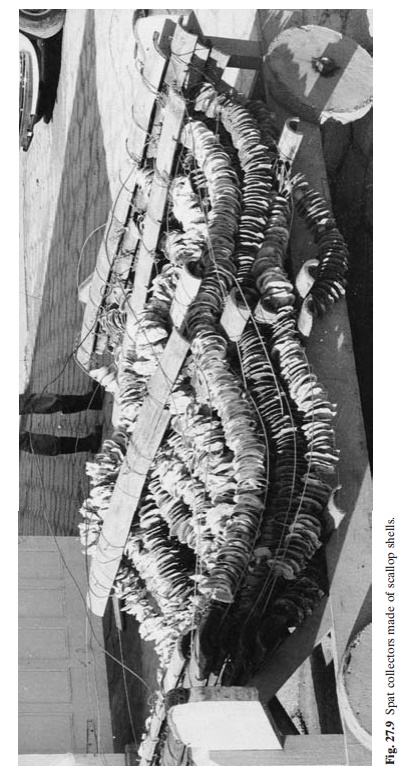

The most common collector used in Japan and many other countries consists of scallops or oyster shells strung on a wire, with cut pieces (1–2 cm long) of tubes or small hollow bamboos as spacers to keep the shells apart and expose more surface for spat attachment (fig. 27.9). Such strings of shells are suspended from rafts, long lines or specially constructed bamboo frames. In some cases, the strings are laid horizontally on the bamboo frames, instead of

When oyster seed is to be used for bottom growing, Japanese spat producers use only oyster shells as collectors, without spacers. Seed oysters attached to the underside of scallop shells, when sown on the sea bottom, are not likely to survive. The Japanese producers subject the collected spat to a hardening process before export. About a month after setting, when the seed oysters measure about 5–10mm in diameter, the collectors are transferred to hardening racks and laid horizontally on the platforms. The spat are exposed at each low tide for at least four hours. Hardened spat are better able to survive long-distance transport and have less mortality during their growth to seed oysters.

As mentioned earlier, some farmers use chicken wire or expandable plastic mesh bags of various shapes for catching spat and also for on-growing. This type of collector has the advantage that when there is heavy setting it is fairly easy to thin and separate out the spat. This is particularly important in growing oysters of uniform size and shape for consumption on the half-shell.

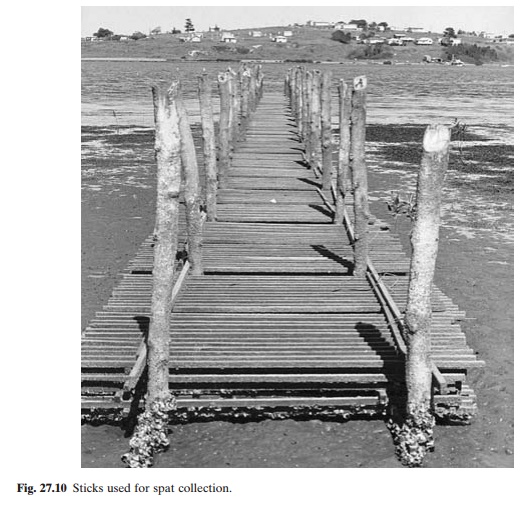

In areas where stake or stick culture is practised, spat are generally collected on cement-dipped wooden, reinforced concrete, or asbestos cement sticks, and their on-growing is also carried out on the same substrate. Plastic or fibreglass sticks can be used (fig. 27.10), if the spat are to be removed from

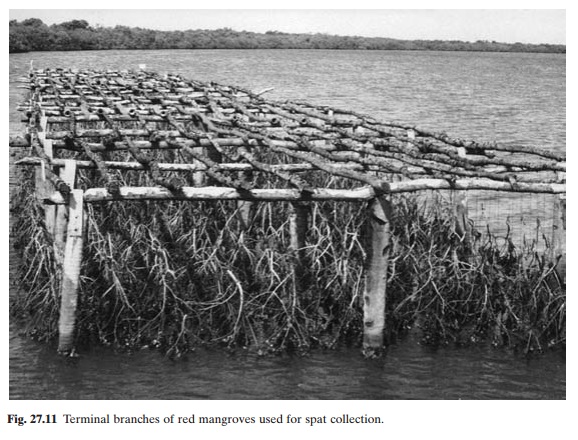

The spat of mangrove oysters, as the name implies, attach themselves in nature to man-grove roots. Nikolic et al. (1976) described the use of terminal branches of the red mangrove suspended from a wooden framework for spat collection (fig. 27.11) as well as on-growing. Other types of collectors, especially strings of oyster or scallop shells and wooden sticks, have also been used successfully for collecting man-grove oyster spat.

Hatchery production of seed oysters

In recognition of the need for alternative means of producing seed oysters, other than uncertain collection from the wild, efforts have been made to develop hatchery techniques for the more important species. Declining stocks of oysters in traditional oyster grounds and the consequent reduction in the availability of spat, as also the need to import spat every year, served as further inducement to these efforts. In the absence of controlled breeding, oyster farming had no access to the benefits of genetic selection and hybridization. As a result of many years of research, starting from the early 19th century, controlled reproduction and larval rearing of the more important oysters and several other bivalve species have become possible (Loosanoff and Davis, 1963). Hatchery technologies for commercial application are suitable for the Pacific, Japanese, the American and the European oysters. The basic techniques used in hatcheries for these species, and in fact for all bivalves, are very similar, but variations and modifications are made to suit local conditions and species. According to Chew (1986) ‘no two hatcheries are alike, and anyone who starts one can expect several years of experimentation before having any assurance of success’.

The economics of hatchery operation also depend very much on local conditions and on whether the farmers have access to wild seed stock. Most hatchery production of seed oysters is performed in the USA, followed by the UK and France on a smaller scale. Small-scale hatcheries are reported to have been established in Chile, Mexico and Australia as well (Chew, 1986).

An adequate supply of unpolluted, clear water of the required salinity, and if possible optimum temperature, is a major criterion for site selection for an oyster hatchery, as well as the normal site requirements for all aquaculture hatcheries. A salinity above 20 ppt and water temperature not exceeding 20°C are recommended for the Pacific oyster, and 11–17 ppt salinity and a 19–25°C temperature range for the American oyster. However, the purpose of an oyster hatchery is to control and manipulate the temperature regime so that mature oysters will be available for spawning at any time, through a process of brood conditioning. For this purpose it is essential to select sufficiently fat spawners in good condition, grown in areas suitable for rapid growth and with similar salinity regimes. At least 30 per cent of the brood stock should be 1.5–2 years old, as a good percentage of them will be males, and the rest can be about 2.5 years old and will have a preponderance of females. It is advisable to have a mixture of spawners grown in different localities, to ensure a varied gene pool.

The brood stock is conditioned for spawning by placing the required number (usually about 50–150 oysters) in flow-through conditioning flumes or trays, supplied with water of the right temperature for maturation. The conditioning may take up to eight weeks, during which period they are fed on algae. Supplementary feeding with corn starch is recommended to increase the glycogen reserve of the oysters. When fully mature, the European oyster spawns spontaneously at temperatures of 16–26°C. For species of Crassostrea it is necessary to manipulate the water temperature to induce spawning. The temperature is first raised to 25°C and then to 30°C over a half-hour period. After this, the temperature is made to fluctuate between 25 and 30°C. These temperature variations normally induce spawning, butif they fail the conditioning trays or flumes are drained and then refilled with fresh sea water of the required temperature. This is likely to stimulate spawning. An additional means of stimulation is a suspension of gametes (eggs or sperm) spawned by other oysters or gametes taken from conditioned oysters. It has been observed that there are distinct differences in the response of spawners from different geo-graphic populations and in their temperature requirements. In such cases a series of temperature shocks is tried, and if even this does not succeed, eggs and sperm are stripped from mature brood stock and fertilized.

As indicated earlier, there is a major difference in the fertilization and incubation of eggs in Crassostrea and Ostrea, and so they have to be treated differently in the hatchery. Crassostrea which have begun to spawn or show signsof spawning are transferred to separate containers, in order to facilitate separate collection of the spawned eggs and sperm. As soon as spawning ceases, the eggs and sperm are removed and the spawners transferred to cold running sea water. After the eggs are sieved to remove all extraneous matter, they are fertilized with a suspension of sperm. Usually in commercial operations, the eggs of several females (at least two individuals) and the sperm of several males are mixed, to ensure a mixed gene pool. A ratio of 2–4 ml dense sperm suspension for every 4 l egg suspension (containing about a million eggs) has been recommended. Too much sperm can result in abnormal embryonic development due to polyspermy caused by the penetration of the eggs by more than one sperm. Too few sperms mean lower rates of fertilization. The fertilized eggs are diluted with salt water to a concentration of about 200 eggs per ml and allowed to develop for about 24 hours at 25°C into straight-hinged veligers measuring 75–80 mm.

The European oyster, Ostrea edulis, is larviparous and retains the eggs and larvae within the mantle cavity for about seven to ten days after spawning. Piles of eggs around the shell margin show that spawning has occurred. The larvae are released in swarms when they measure about 170 mm, much larger than the straight-hinge stage of Crassostrea. Ostreachilensis has a prolonged larval incubation andthe larvae are released only when ready to settle (Korringa, 1976). This reduces the need for rearing larvae for long periods.

The larvae of Crassostrea as well as Ostrea can be reared in suitable culture tanks and fed on algae. A number of methods of producing and feeding algae to oyster larvae have been tried, but most hatcheries produce pure cultures of selected algae and feed them singly or in combination. Methods of algal culture and the species preferred by oysters have been discussed. Isochrys, Phaeodactylum, Platymonas, Monochrysis, Dunaliella and Chlorella are some of the algae which havebeen found to be efficient larval foods at different stages of growth. The batch culture technique is commonly followed, in which large quantities of green water or algae-rich water are produced in a series of steps, starting with pure cultures inoculated into small quantities of sterilized sea water and nutrient solution which are then used to create progressively larger cultures. In the Wells-Glancey method (Wells, 1927), which is an earlier method of algal production, zooplankton and large algae are first removed from the sea water, using a milk separator, and then incubated for 12–24 hours to produce large numbers of small algae. Probably because of inadequate control of the species of algae grown and the deficiencies of the separating mechanisms, this method has not always given satisfactory results (Loosanoff, 1971).

Various types and sizes of tanks are used for larval rearing. Most of them are large, of at least 500 l capacity. The number of larvae released in the tanks are estimated by counting samples from a suspension. The tanks are stocked at the rate of about 10 per ml. The water supply is generally sand-filtered and UV-sterilized. A temperature of about 25°C, salinity of 25–30 ppt and heavy aeration are maintained. Depending on local conditions, the rearing water is changed once to three times a week. Most hatcheries grade the larvae according to size, and only the best-growing ones are allowed to reach settlement. The feeding rate is carefully monitored and the species of algae are varied as the larvae grow to ensure optimum growth at each stage. A starting concentration of 30 000 algal cells/ml water for the first week, followed by 50000 cells/ml during the second week and 80 000 cells/ml during the third week has been suggested (Breese and Malouf, 1975).

The larvae are fed at this concentration once a day during the first week, and twice a day thereafter.

Crassostrea are ready to settle after threeweeks and Ostrea after two weeks of rearing, at 24–28°C. Hatcheries produce spat settled on cultch or the so-called cultchless seed. The most common cultch used in hatcheries are mollus-can shells. Many hatcheries use plastic bags or baskets containing cleaned oyster shells for spat setting in large tanks.

Several methods of producing cultchless spat are in practice. The spat may be allowed to settle on a flexible sheet of smooth plastic, in which case they can be easily removed soon after setting or after a period of growth. An alternative is to use crushed shell chips or calcium carbonate particles as substrates, as each piece will have only one or two spat attached. A third method is the use of vinyl-coated wire trays dipped in concrete and sprinkled with oyster shell chips to collect the spat. Such trays are said to be easier to clean and allow better use of space. Cultchless oysters have to be carefully reared in flumes or trays until they grow to a diameter of at least 2.5 cm.

Spat are sold by hatcheries when they are 4– 6 mm in diameter and about three months old. Until then, they are reared in water temperatures of 25–30°C. The feeding rate is increased a week after setting to 100 000–150 000 cells/ml per day. Before the spat are removed from the hatchery for sale or planting, the temperature is changed gradually to avoid a sudden temperature shock.

Burrell (1985) described a system developed on the west coast of the USA for transport of eyed larvae of the Pacific oyster. The larvae are concentrated on a screen, placed on a damp cloth and wrapped in wet paper towels for transport in plastic coolers. At temperatures between 1 and 4°C, the larvae can be held for about seven days without much loss. At the destination they can be set on substrates in the same way as in hatcheries.

Related Topics