Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Patients With Hypertension

Primary Hypertension

Primary Hypertension

Between 20% and 25% of the adult population in the United States has hypertension (Burt et al., 1995b). Of this population, between 90% and 95% have primary hypertension, meaning that the reason for the elevation in blood pressure cannot be iden-tified. The remaining 5% to 10% of this group have high blood pressure related to specific causes, such as narrowing of the renal arteries, renal parenchymal disease, hyperaldosteronism (miner-alocorticoid hypertension) certain medications, pregnancy, and coarctation of the aorta (Kaplan, 2001). Secondary hypertension is the term used to signify high blood pressure from an identified cause.

Hypertension

is sometimes called “the silent killer” because people who have it are often

symptom free. In a national survey (1991 to 1994), 32% of people who had

pressures exceeding 140/90 mm Hg were unaware of their elevated blood pressure

(Burt et al., 1995a). Once identified, elevated blood pressure should be

monitored at regular intervals because hypertension is a lifelong condition.

Hypertension

often accompanies risk factors for atheroscle-rotic heart disease, such as dyslipidemia (abnormal blood fat

levels) and diabetes mellitus. The incidence of hypertension is higher in the

southeastern United States, particularly among African Americans. Cigarette

smoking does not cause high blood pressure; however, if a person with

hypertension smokes, his or her risk of dying from heart disease or related

disorders increases significantly.

High blood pressure can be viewed in three ways: as a sign, a risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, or a disease.

As a

sign, nurses and other health care professionals use blood pressure to monitor

a patient’s clinical status. Elevated pressure may indicate an excessive dose

of vasoconstrictive medication or other problems. As a risk factor,

hypertension contributes to the rate at which atherosclerotic plaque

accumulates within arterial walls. As a disease, hypertension is a major

contributor to death from cardiac, renal, and peripheral vascular disease.

Prolonged

blood pressure elevation eventually damages blood vessels throughout the body,

particularly in target organs such as the heart, kidneys, brain, and eyes. The

usual consequences of prolonged, uncontrolled hypertension are myocardial

infarction, heart failure, renal failure, strokes, and impaired vision. The

left ventricle of the heart may become enlarged (left ventricular hyper-trophy)

as it works to pump blood against the elevated pressure. An echocardiogram is

the recommended method of determining whether hypertrophy (enlargement) has

occurred.

Pathophysiology

Although

the precise cause for most cases of hypertension cannot be identified, it is

understood that hypertension is a multifactorial condition. Because

hypertension is a sign, it is most likely to have many causes, just as fever

has many causes. For hypertension to occur, there must be a change in one or

more factors affecting pe-ripheral resistance or cardiac output (some of these

factors are out-lined in Fig. 32-1). In addition, there must also be a problem

with the control systems that monitor or regulate pressure. Single gene

mutations have been identified for a few rare types of hypertension, but most

types of high blood pressure are thought to be polygenic (mutations in more

than one gene) (Dominiczak et al., 2000).

Several

hypotheses about the pathophysiologic bases of ele-vated blood pressure are

associated with the concept of hyper-tension as a multifactorial condition.

Given the overlap among these hypotheses, it is likely that aspects of all of

them will even-tually prove correct. Hypertension may be caused by one or more

of the following:

· Increased sympathetic

nervous system activity related to dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system

· Increased renal

reabsorption of sodium, chloride, and water related to a genetic variation in

the pathways by which the kidneys handle sodium

· Increased activity of

the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone sys-tem, resulting in expansion of

extracellular fluid volume and increased systemic vascular resistance

· Decreased vasodilation

of the arterioles related to dysfunction of the vascular endothelium

· Resistance to insulin

action, which may be a common fac-tor linking hypertension, type 2 diabetes

mellitus, hyper-triglyceridemia, obesity, and glucose intolerance

Gerontologic Considerations

Structural

and functional changes in the heart and blood vessels contribute to increases

in blood pressure that occur with age. The changes include accumulation of

atherosclerotic plaque, frag-mentation of arterial elastins, increased collagen

deposits, and im-paired vasodilation. The result of these changes is a decrease

in the elasticity of the major blood vessels. Consequently, the aorta and large

arteries are less able to accommodate the volume of blood pumped out by the

heart (stroke volume), and the energy that would have stretched the vessels

instead elevates the systolic blood pressure. Isolated systolic hypertension is

more common in older adults.

Clinical Manifestations

Physical

examination may reveal no abnormalities other than high blood pressure.

Occasionally, retinal changes such as hemorrhages, exudates (fluid

accumulation), arteriolar narrowing, and cotton-wool spots (small infarctions)

occur. In severe hypertension, papilledema (swelling of the optic disc) may be

seen. People with hypertension can be asymptomatic and remain so for many

years. However, when specific signs and symptoms appear, they usually indicate

vascular damage, with specific manifestations related to the organs served by

the involved vessels. Coronary artery dis-ease with angina or myocardial

infarction is a common conse-quence of hypertension. Left ventricular

hypertrophy occurs in response to the increased workload placed on the

ventricle as it contracts against higher systemic pressure. When heart damage

is extensive, heart failure ensues. Pathologic changes in the kidneys (indicated

by increased blood urea nitrogen [BUN] and creati-nine levels) may manifest as

nocturia. Cerebrovascular involve-ment may lead to a stroke or transient

ischemic attack (TIA), manifested by alterations in vision or speech,

dizziness, weakness, a sudden fall, or temporary paralysis on one side

(hemiplegia). Cerebral infarctions account for most of the strokes and TIAs in

patients with hypertension.

Assessment and Diagnostic Evaluation

A thorough health history and physical examination are necessary. The retinas are examined, and laboratory studies are performed to assess possible target organ damage. Routine laboratory tests in-clude urinalysis, blood chemistry (ie, analysis of sodium, potassium, creatinine, fasting glucose, and total and high-density lipoprotein [HDL] cholesterol levels), and a 12-lead electrocardiogram. Left ventricular hypertrophy can be assessed by echocardiography. Renal damage may be suggested by elevations in BUN and creatinine levels or by microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria. Additional studies, such as creatinine clearance, renin level, urine tests, and 24-hour urine protein, may be performed.

A risk

factor assessment, as advocated by the JNC VI, is needed to classify and guide

treatment of hypertensive people at risk for cardiovascular damage. Risk

factors and cardiovascular problems related to hypertension are presented in

Chart 32-1 and Table 32-3.

Medical Management

The

goal of hypertension treatment is to prevent death and complications by

achieving and maintaining the arterial blood pressure at 140/90 mm Hg or lower.

The JNC VI specified a lower goal pressure of 130/85 mm Hg for people with

diabetes mellitus or with proteinuria greater than 1 g per 24 hours ( JNC VI,

1997).

The

optimal management plan is inexpensive, simple, and causes the least possible

disruption in the patient’s life.

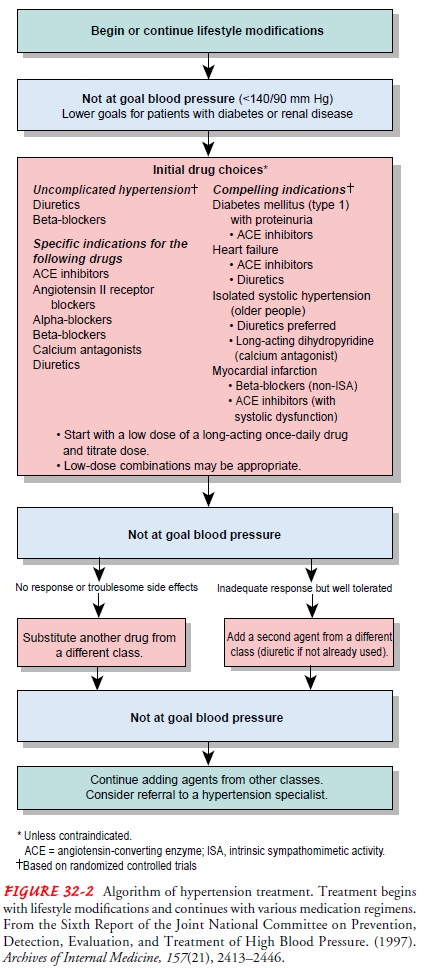

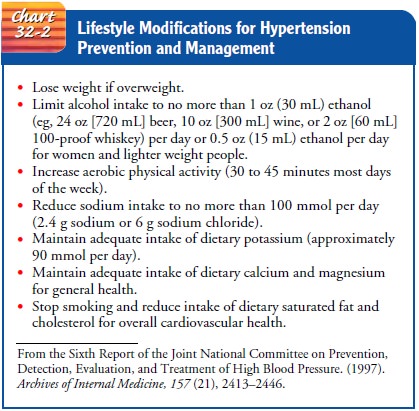

The

management options for hypertension are summarized in the treatment algorithm

issued in the Sixth Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention,

Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (1997) (Fig. 32-2)

and in Chart 32-2, which lists recommended lifestyle modifications. The

clinician uses the algorithm in conjunction with the riskfactor assessment data

and the patient’s blood pressure category to choose the initial and subsequent

treatment plans for patients.Research findings demonstrate that weight loss,

reduced alcohol and sodium intake, and regular physical activity are effective

life-style adaptations to reduce blood pressure (Appel et al., 1997; Cushman et

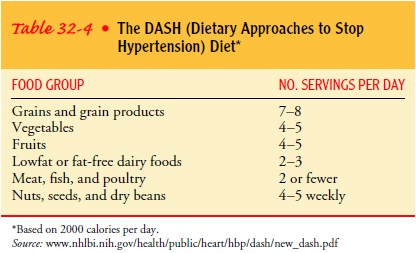

al., 1998; Hagberg et al., 2000; Sacks et al., 2001). Studies show that diets

high in fruits, vegetables, and low-fat diary products can prevent the

development of hypertension and can lower elevated pressures. Table 32-4

delineates the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet.

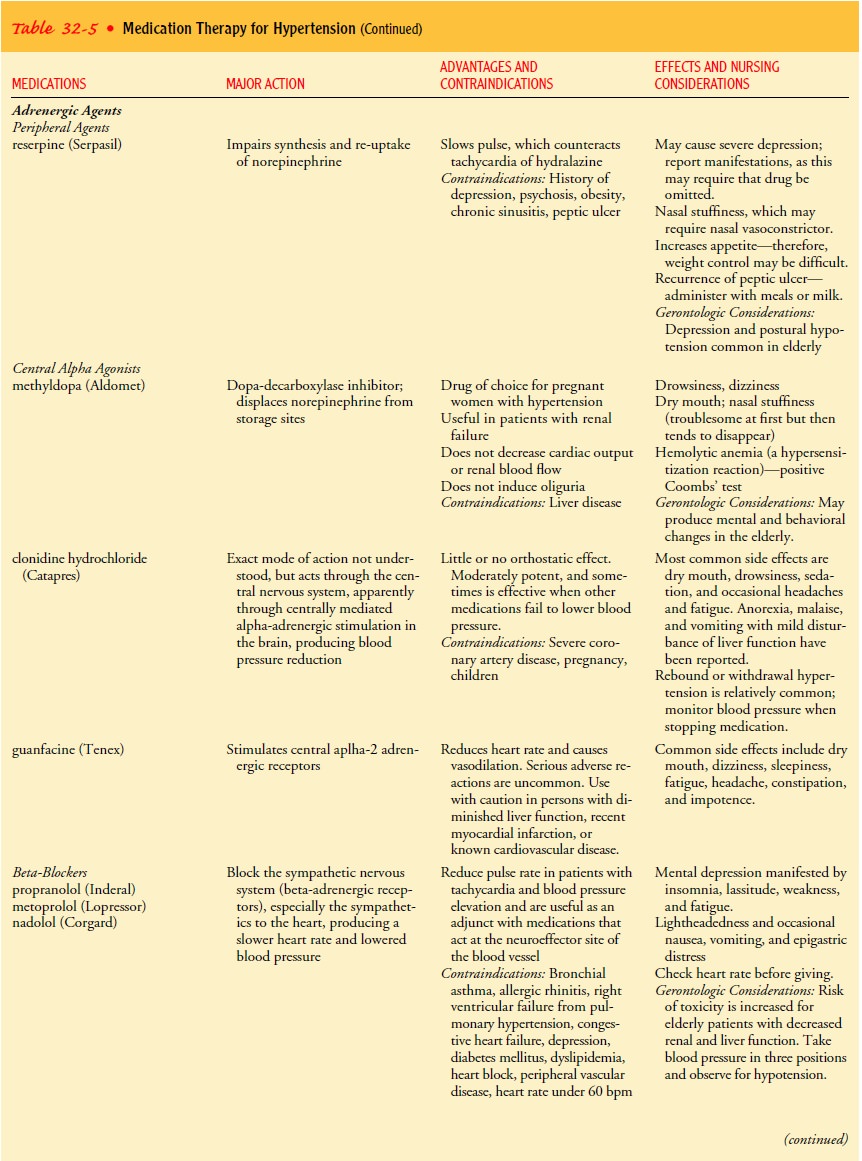

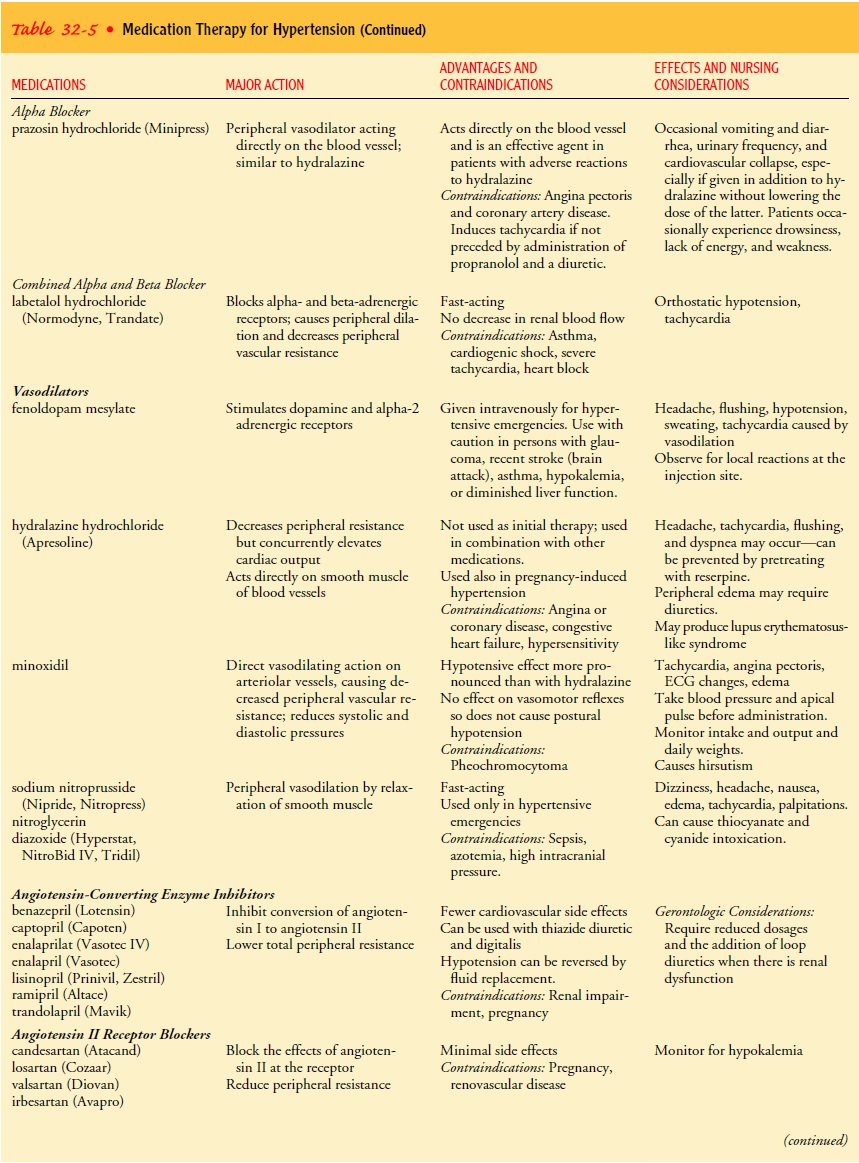

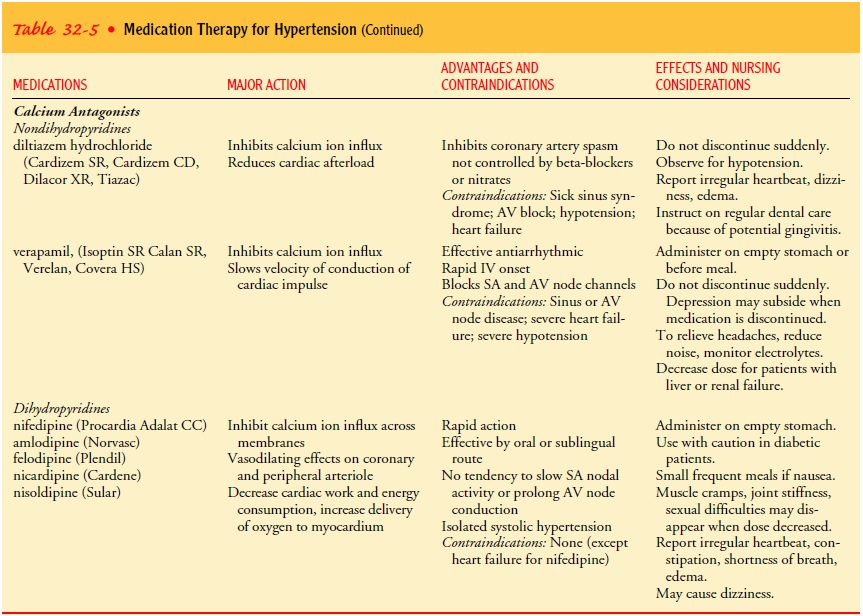

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

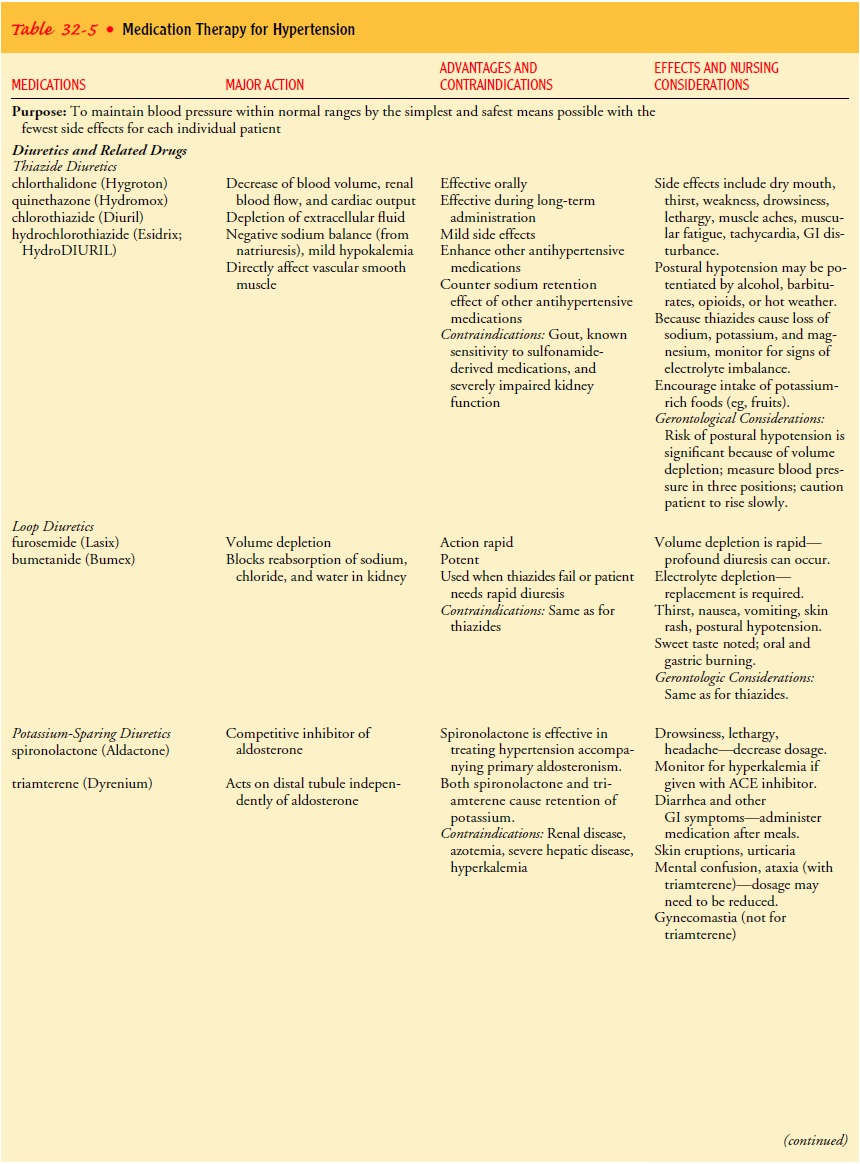

For

patients with uncomplicated hypertension and no specific in-dications for

another medication, the recommended initial med-ications include diuretics,

beta-blockers, or both. Patients are first given low doses of medication. If

blood pressure does not fall to less than 140/90 mm Hg, the dose is increased

gradually, and ad-ditional medications are included as necessary to achieve

control. Table 32-5 describes the various pharmacologic agents used in treating

hypertension. When the blood pressure has been less than 140/90 mm Hg for at

least 1 year, gradual reduction of the types and doses of medication is

recommended. To promote compliance, clinicians try to prescribe the simplest

treatment schedule possible, ideally one pill once each day.

Gerontologic Considerations

Hypertension,

particularly elevated systolic blood pressure, in-creases the risk of death and

complications in elderly patients. Treatment reduces this risk. Like younger

patients, elderly pa-tients should begin treatment with lifestyle

modifications. If med-ications are needed to achieve the blood pressure goal of

less than 140/90 mm Hg, the starting dose should be one-half that used in younger

patients.

Related Topics