Chapter: Biology of Disease: Pathogens and Virulence

Pathogens and Virulence: Introduction

PATHOGENS AND VIRULENCE

INTRODUCTION

The body is exposed to many pathogenic microorganisms

and multicellular parasites. Most microorganisms found associated with the body

are harmless and live as commensals or symbionts but others cause disease and

are known as pathogens. Infection, from the Latin ‘inficere’

(to put in), is the successful persistence and/or multiplication of the

pathogen on or within the host. In this respect, pathogenesis may be defined as the molecular and biochemical

mechanisms that allow pathogens to cause diseases. Mummies preserved in ancient

Egypt and elsewhere display evidence that infectious diseases have always been

a threat. The emergence of new pathogens and the development of resistance to

current treatments for existing pathogens means that infectious diseases will

probably always be with us.

Many antibiotic drugs are available to treat

infectious diseases and, in many cases, will effect a cure. It is, however,

possible for them to exacerbate the problem since the drug can remove

commensals allowing antibiotic resistant pathogens to flourish. Also, an

adequate immune response is often necessary, since drugs alone may fail to

eliminate the infection. Thus all pathogens must overcome the defense systems

present in their hosts .

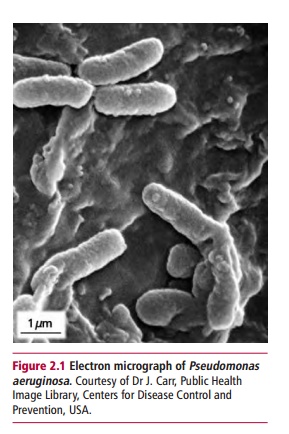

Some pathogens regularly cause diseases while others

do not. For example, Pseudomonas

aeruginosa (Figure 2.1) can cause

overwhelming disease inpatients whose defense systems are compromized but not

in those with intact defenses. It is likely that any microorganism with the

ability to live in or on humans will sometimes become an opportunistic pathogen especially if the balance between the usual

microorganisms present and the immune system is disturbed. Thus bacteria which

are normally harmless, but which are opportunistic pathogens, can cause

infections under certain conditions. For example, wounds can become badly

infected with bacteria that normally exist on the skin, and bacteria that

normally live in the gut can cause serious infections if peritonitis allows the

gut contents to enter the peritoneum. In general, these infections are not

transferable to other healthy humans.

The success of pathogenic microorganisms depends on

their ability to colonize host tissues and to counter the host’s defense

mechanisms. Virulence is measured by the infective

dose and the severity of the disease caused. For example, as few as 10 to

100 Shigella dysenteriae cells can

cause shigellosis but more than 10 000 cells are needed of the less virulent

salmonella or cholera bacteria. True pathogens are equipped with a range of virulence factors. The strains of some

bacterial species, such as pathogenic forms of Escherichia coli (Figure 2.2)

can produce different virulence factors that cause, for example, diarrhea,

urinary tract infections or sepsis. Other strains, however, do not produce

virulence factors or do so to a lesser extent and are therefore not pathogenic,

except when they infect an immunocompromized host.

A pathogen must be transmitted from a source to the

patient. Direct contact between hosts is the most obvious form of transmission

but coughs and sneezes (aerosols), food, water and arthropod vectors are all

used by various pathogens. The long-term survival of pathogenic microorganisms

also depends on maintaining their infectivity during transmission from host to

host. Diseases that are transmitted from animals to humans are called zoonoses, while humans who harbor a

pathogen but are asymptomatic arecalled carriers.

Related Topics