Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

ObsessiveŌĆōCompulsive Disorder Versus Other Disorders

ObsessiveŌĆōCompulsive Disorder Versus Other Anxiety

Disorders

Both OCD and the other anxiety disorders are characterized by the use of

avoidance to manage anxiety. However, OCD is distin-guished from these

disorders by the presence of compulsions. For OCD patients with preoccupying

fears or worries but no rituals, several other features may be useful in establishing

the diagnosis of OCD. In social phobia and specific phobia, fears are

circum-scribed and related to specific triggers (in specific phobia) or so-cial

situations (in social phobia). Although circumscribed situa-tions may initially

trigger obsessions and compulsions in OCD, triggers in OCD become more

generalized over time, unlike the triggers in social and specific phobias, in

which the evoking situ-ations remain circumscribed.

As many as 60% of people with OCD experience full-blown panic symptoms.

However, unlike panic disorder, in which panic attacks occur spontaneously,

panic symptoms occur in OCD only during exposure to specific feared triggers

such as contaminated objects. The worries that are present in generalized

anxiety dis-order (GAD) are more ego syntonic and involve an exaggeration of

ordinary concerns, whereas the obsessional thinking of OCD is more intrusive,

is limited to a specific set of concerns (e.g., contamination, blasphemy), and

usually has an irrational, sense-less, or unreasonable quality. Also, whereas

the worry of GAD is considered primarily thoughtlike in nature, obsessional

symp-toms may consist of thoughts, impulses, or images.

ObsessiveŌĆōCompulsive Disorder Versus Psychotic Disorders

One question is how to differentiate OCD from psychotic disorders such

as schizophrenia and delusional disorder. An-other question is how to

distinguish OCD with insight from OCD without insight (delusional OCD). One

distinguishing feature between OCD and the psychotic disorders is that the latter

are not characterized by prominent ritualistic behaviors. If compulsions are

present in a patient with prominent psy-chotic symptoms, the possibility of a

comorbid OCD diagnosis should be considered. Furthermore, although

schizophrenia may be characterized by obsessional thinking, other

character-istic features of the disorder, such as prominent hallucinations or

thought disorder, are also present. With regard to delusional disorder,

paranoid and grandiose concerns are generally not considered to fall under the

OCD rubric. However, some other types of delusional disorder, such as the

somatic and jealous types, seem to bear a close resemblance to OCD and are not

always easily distinguished from it. It will be interesting to see whether

future research indicates that certain types of so-matic delusional disorder

(e.g., the delusional variant of hypo-chondriasis) and the jealous type of

delusional disorder (also referred to as pathological jealousy) are actually

variants of OCD.

The second issue noted above ŌĆō how to distinguish OCD with insight from

OCD without insight ŌĆō is complex. As previ-ously discussed, insight in OCD is

increasingly being recognized as spanning a spectrum from good to poor to

absent. Both clini-cal observations and research findings indicate that some

indi-viduals hold their obsessional concerns with delusional intensity and

believe that their concerns are reasonable. In DSM-IV, delu-sional OCD may be

double-coded as both OCD and delusional disorder or as both OCD and psychotic

disorder not otherwise specified, in other words, patients with delusional OCD

would receive both diagnoses. This double coding reflects the fact that it is

unclear whether OCD with insight and OCD without insight constitute the same or

different disorders. Further research using validated scales to assess insight

in OCD is needed to shed light on this question.

ObsessiveŌĆōCompulsive Disorder Versus Impulse Control Disorders

Differential diagnosis questions have been raised with regard to

kleptomania, trichotillomania, pathological gambling and other disorders

involving impulsive behaviors. Several features have been said to distinguish

these disorders from OCD. For ex-ample, compulsions ŌĆō unlike behaviors of the

impulse control disorders ŌĆō generally have no gratifying element, although they

do diminish anxiety. In addition, the affective state that drives the behaviors

associated with these disorders may differ. In OCD, fear is frequently the

underlying drive that leads to com-pulsions, which, in turn, decrease anxiety.

In the impulse control disorders, patients frequently describe heightened

tension, but not fear, preceding an impulsive behavior. However, OCD and the

impulse control disorders have some features in common. Re-search is ongoing to

explore the relationship between OCD and the impulse control disorders by

examining similarities and dif-ferences in treatment response, biological

markers and familial transmission.

ObsessiveŌĆōCompulsive Disorder Versus TouretteŌĆÖs Disorder

Complex motor tics of TouretteŌĆÖs disorder may be difficult to

distinguish from OCD compulsions. Both tics and compulsions are preceded by an

intrusive urge and are followed by feelings of relief. However, OCD compulsions

are usually preceded by both anxiety and obsessional concerns, whereas, in

TouretteŌĆÖs disorder, the urge to perform a tic is not preceded by an

obses-sional fear. This distinction breaks down to some extent when considering

the ŌĆ£just rightŌĆØ perceptions of some patients with OCD. The ŌĆ£just rightŌĆØ

perception refers to the need to perform a certain motor action, such as

touching, tapping, checking, order-ing, arranging, or counting, until it feels

right. Determining when an action has been performed enough or perfectly may

depend on tactile, visual, or auditory perceptions. In a study of patients with

TouretteŌĆÖs disorder and OCD symptoms, most patients could distinguish between

the mental urge to do something repeatedly until it felt right and a physical

urge to perform a motor tic. How-ever, it is sometimes difficult for

psychiatrists to distinguish be-tween complex tics and compulsions, especially

when a patient has both disorders.

ObsessiveŌĆōCompulsive Disorder Versus Hypochondriasis

Fears of illness that occur in OCD, referred to as somatic obses-sions,

may be difficult to distinguish from hypochondriasis. Usu-ally, however,

patients with somatic obsessions have other cur-rent or past classic OCD

obsessions unrelated to illness concerns. Patients with OCD also often engage

in classic OCD rituals, such as checking or reassurance seeking, in an attempt

to diminish their illness concerns. Unlike patients with OCD, patients with

hypochondriasis experience somatic and visceral sensations. Although insight

and resistance have been used to distinguish OCD from hypochondriasis, with the

concern in hypochondria-sis being said to be egosyntonic (realistic and totally

justified) and that of OCD to be egodystonic (unacceptable and undesirable

thoughts, actions, or both), studies have demonstrated a range of insight in

OCD. Attempting to differentiate these disorders by degree of insight or

egosyntonicity may therefore be of limited usefulness.

ObsessiveŌĆōCompulsive Disorder Versus Body Dysmorphic Disorder

Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), a preoccupation with an im-agined or

slight defect in appearance (e.g., thinning hair, facial scarring, or a large

nose), has many similarities to OCD (Phillips, 1991). Patients with BDD

experience obsessional thinking about the supposed defect and usually engage in

associated repetitive ritualistic behaviors, such as mirror checking and

reassurance seeking. Preliminary evidence suggests that BDD also appears

similar to OCD in terms of age of onset, course of illness and other variables.

Nonetheless, emerging data suggest that there are some important differences

between the two disorders, and they are currently classified separately in

DSM-IV. Insight, for example, is more frequently impaired in BDD than in OCD.

If the content of a patientŌĆÖs obsessions involves a concern about a supposed

defect in appearance, BDD, rather than OCD, is the diagnosis that should be

given.

ObsessiveŌĆōCompulsive Disorder Versus ObsessiveŌĆōCompulsive Personality Disorder

ObsessiveŌĆōcompulsive personality disorder is a lifelong mala-daptive

personality style characterized by perfectionism, exces-sive attention to

detail, indecisiveness, rigidity, excessive devo-tion to work, restricted

affect, lack of generosity and hoarding. OCD and OCPD have historically been

considered variants of the same disorder on a continuum of severity, with OCD

viewed as the more severe manifestation of illness. Contrary to this notion,

studies using structured interviews to establish diagnosis have found that not

all patients with OCD also have OCPD. One rea-son for the perception that these

disorders are linked lies in the frequency of several OCPD traits in patients

with OCD. In one study, the majority of 114 patients with OCD had perfectionism

and indecisiveness (82 and 70, respectively). In contrast, other OCPD traits,

such as restricted affect, excessive devotion to work and rigidity, were seen

infrequently.

Although perfectionism and indecisiveness are relatively common traits

in patients with OCD, the distinction between OCD and OCPD is important, and

several guidelines may be useful in distinguishing them. Unlike OCPD, OCD is

character-ized by distressing, time-consuming egodystonic obsessions and

repetitive rituals aimed at diminishing the distress engendered by obsessional

thinking. One of the hallmarks that traditionally has been used to distinguish

OCD from OCPD is that, in con-trast, OCPD features are considered egosyntonic.

In addition, as previously noted, the traits of restricted affect, excessive

devo-tion to work and rigidity are generally characteristic of OCPD but not

OCD. Although useful, these guidelines are not absolute, and some patients defy

easy categorization. Some patients, for example, spend hours each day engaged

in egosyntonic behav-iors such as excessive cleaning; such patients may seek

treatment not because they are disturbed by their behaviors but because the

behaviors cause problems in functioning or family friction. It is unclear

whether some of these patients should be diagnosed with OCPD or subthreshold

OCD.

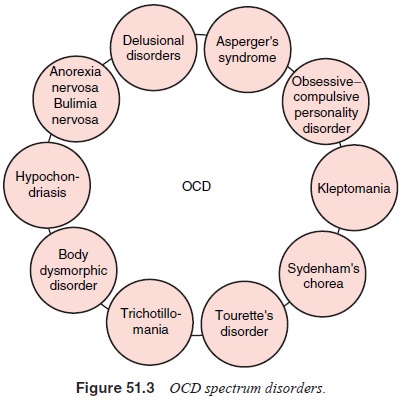

ObsessiveŌĆōCompulsive Spectrum Disorders

Certain disorders other than OCD, such as BDD, hypochondria-sis, and

eating disorders, are characterized by obsessional think-ing and/or ritualistic

behaviors. On the basis of these apparent similarities with OCD, the concept of

OCD spectrum disorders has been developed. They have been defined as disorders

that share features with OCD (Hollander, 1993) and are posited to have

ŌĆ£spectrum membershipŌĆØ on the basis of their similarities with OCD across

multiple domains. These domains include not only symptoms but also treatment

response, comorbidity, joint familial loading, sex ratio, age at onset, course,

premorbid per-sonality characteristics and presumed cause. Cause is inferred

from characteristics such as neurological deficits, response to bi-ological challenges,

biochemical indices, brain imaging patterns (functional and anatomical) and

epidemiological risk factors. It is worth noting that there are currently no

operational criteria for what constitutes an OCD spectrum disorder; for

example, in which of the preceding domains must similarities be documented, and

how similar in each domain must the disorder be to OCD?

Disorders postulated to be OCD spectrum disorders in-clude BDD,

hypochondriasis, eating disorders, ŌĆ£groomingŌĆØ dis-orders such as nail biting

and trichotillomania, and the impulse

disorders

(see Figure 51.3). Of interest is a recent study investi-gating the frequency

of these disorders in first-degree relatives of people with OCD. BDD,

hypochondriasis, any eating disorder (although not anorexia or bulimia

individually) and grooming disorders (but not the impulse control disorders)

were found more frequently in probands with OCD than in general population

con-trols. In addition, BDD and grooming disorders (although not the other disorders)

were significantly more common in the first-degree relatives of OCD probands

than in relatives of controls (Bienvenu et al., 2000). This finding suggests

that certain of the proposed OCD spectrum disorders may have a familial link to

OCD. The relationship of these disorders with OCD is an area in which exciting

research will be conducted in coming years.

Related Topics