Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Augmentation Strategies

Augmentation Strategies

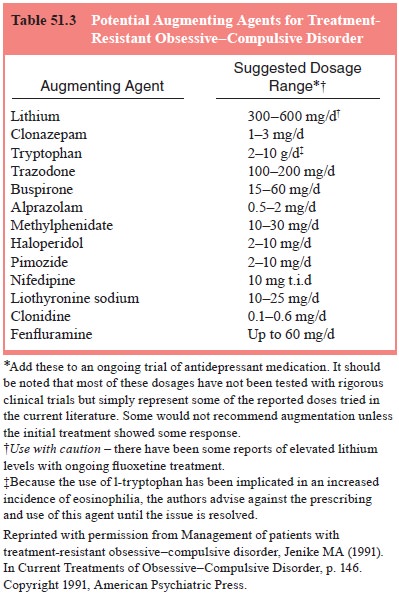

If a patient has had only a partial response to an antiobsessional agent

of adequate dose and duration, the next question is whether to change the SRI

or add an augmenting agent. Current clinical practice suggests that if there is

no response at all to an SRI, it may be best to change to another SRI. However,

if there has been some response to treatment, an augmentation trial of at least

2 to 8 weeks may be warranted. No augmentation agent has been firmly

established as efficacious. Many questions about augmen-tation remain

unanswered, including the optimal duration of aug-mentation, comparative

efficacy of different agents, predictors of response and mechanism of action.

Nonetheless, these agents do help some patients significantly, and thus their

systematic use should be considered (see Table 51.3).

In patients with severe symptoms or comorbid psycho-sis or tic disorder,

pimozide 1 to 3 mg/day, haldol 2 to 10 mg/ day, and other neuroleptic agents

(risperdone 2–8 mg/day and olanzapine 2.5–10 mg/day) have been used with some

success.

However, the use of a neuroleptic agent should be considered carefully

in light of the risk of extrpyramidal symptoms and side effects such as weight

gain, lethargy and tardive dyski-nesia. Thus, when a neuroleptic drug is used,

target symptoms should be established before beginning treatment, and the

med-ication discontinued within several months if target symptoms do not

improve.

The use of lithium (300–600 mg/day) and buspirone (up to 60 mg/day) as

augmentation agents has also been explored. Both agents looked promising in

open trials but failed to be effective in more systematic trials. Augmentation

with fenfluramine (up to 60 mg/day), clonazepam (up to 5 mg/day), clonidine

(0.1–0.6 mg/day) and trazodone (100–200 mg/day), as well as the combination of

clomipramine with any of the SSRIs, has had anecdotal success but has not been

evaluated in methodologically rigorous studies. Some potential augmenting

agents and their dosage ranges are presented in Table 51.3.

Behavioral Therapy

Behavioral therapy is effective for OCD both as a primary treat-ment and

as an augmentation agent. This form of therapy is based on the principle of

exposure and response prevention. The patient is asked to endure, in a

graduated manner, the anxiety that a specific obsessional fear provokes while

refraining from compulsions that allay that anxiety. The principles behind the

ef-ficacy of treatment are explained to the patient in the following way.

Although compulsions, either covert or overt, usually im-mediately relieve

anxiety, this is only a short-term solution; the anxiety will ultimately

return, requiring the performance of an-other compulsion. However, if the

patient resists the anxiety and urge to ritualize, the anxiety will eventually

decrease on its own (i.e., habituation will occur), and the need to perform the

ritual will eventually disappear. Thus, behavioral therapy helps the pa-tient

habituate to the anxiety and extinguish the compulsions.

Compulsions, especially overt behaviors like washing rituals, are more

successfully treated by behavioral therapy than are obsessions alone or covert

rituals like mental checking. This is because covert rituals are physically

harder to resist than are rituals like handwashing and checking a door. In fact

washing rituals are the most amenable to behavioral treatment, followed by

checking rituals and then mental rituals.

For rituals that do not constitute overt behaviors, tech-niques other

than exposure and response prevention have been used in conjunction with

exposure and response prevention. These approaches include imaginal flooding

and thought stop-ping. In imaginal flooding, the anxiety provoked by the

obses-sions is evoked by continually repeating the thought, often with the help

of a continuous-loop tape or the reading of a “script” composed by the patient

and therapist, until the thought no longer provokes anxiety. In thought

stopping, an compulsive mental rit-ual (e.g., continually repeating a short

prayer in one’s head) is stopped by simply shouting, making a loud noise, or

snapping a rubber band on the wrist in an attempt to interrupt the thought.

In the early stages of treatment, a behavioral assessment is performed.

During this assessment, the content, frequency, dura-tion, amount of

interference and distress, and attempts to resist or ignore the obsessions and

compulsions are catalogued. An at-tempt is made to clarify the types of

symptoms, any triggers that bring on the obsessions and compulsions, and the

amount and type of avoidance used to deal with the symptoms. For instance, in

the clinical vignette described later, the fact that Ms Z stopped preparing meals

to deal with her obsessional concerns about con-tamination was carefully

documented. The patient, usually with the help of a therapist, then develops a

hierarchy of situations ac-cording to the amount of anxiety they provoke.

During treatment, patients gradually engage in the anxiety-provoking situations

in-cluded in their hierarchy without performing anxiety-reducing rituals.

Behavioral therapy can be used with patients of any age and has been

used in young children, often with the help of a parent as a cotherapist.

However, systematic trials of behavioral treatment in children have not been

performed. More recently, behavioral therapy in a group setting has been

explored and found as effective as, and perhaps even more effective than,

indi-vidual behavioral treatment. The group seems to act as a catalyst for

change by promoting group cohesion, support and encour-agement. Groups can

include patients with different symptoms, though each has a personalized

hierarchy, so that one patient can encourage another. Van Noppen and associates

(1991) included family members in groups because families are often affected by

the patient’s rituals and often function as unwilling participants in rituals.

As members of the group, family members not only gain knowledge and

understanding about OCD but can be co-therapists at home for homework

assignments.

Despite its efficacy, behavioral therapy has limitations. To begin with, about 15 to 25% of patients refuse to engage in behav-ioral treatment initially or drop out early in treatment because it is so anxiety-provoking. Behavioral treatment fails in another 25% of patients for a variety of other reasons, including concomitant depression; the use of central nervous system depressants, which may inhibit the ability to habituate to anxiety; lack of insight; poor compliance with homework, resulting in inadequate expo-sure; and poor compliance on the part of the therapist in enforc-ing the behavioral paradigm. Thus, overall, 50 to 70% of patients are helped by this form of therapy.

One of the issues that has emerged in treating OCD with CBT is the lack

of trained therapists and the cost of repeated indi-vidual exposure sessions.

Thus, in addition to developing group treatments which allow therapists to

treat a number of patients simultaneously, researchers have begun to develop

computer-guided behavior therapy. Several recent reports have shown that while

this modality is not as effective as individual behavior therapy, it does allow

for significant improvement in symptoms over a control condition like

relaxation therapy.

Behavior therapy can be used as the sole treatment of OCD, particularly

with patients whose contamination fears or somatic obsessions make them

resistant to taking medications. Behavioral treatment is also a powerful

adjunct to pharmaco-therapy. Some research appears to indicate that combined

treat-ment may be more effective than pharmacotherapy or behavio-ral therapy

alone, although these findings are still preliminary. Some studies have even

suggested that adding pharmacotherapy to behavior therapy may be particularly

helpful in reducing ob-sessions while compulsions respond to behavior therapy.

From aclinical perspective, it may be useful to have patients begin treat-ment

with medication to reduce the intensity of their symptoms or comorbid

depressive symptoms if present; patients may then be more amenable to

experiencing the anxiety that will be evoked by the behavioral challenges they

perform.

Work by Baxter and colleagues (1992) has illustrated some interesting

correlations between treatment response and changes in neuroanatomy and

neurophysiology. Positron emission tomog-raphy scans with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose were

performed on all patients before and after treatment. Compared with

nonrespond-ers and control subjects, responders in both the medication and the

behavioral treatment groups showed a decrease in activity in the right head of

the caudate nucleus. This finding seems to sup-port the notion that both forms

of treatment bring about similar changes in neurophysiology which lead to

improvement in symp-toms. These results also provide important theoretical

links with the serotonin hypothesis described earlier, as basal ganglion

structures like the caudate nucleus have been postulated to mediate serotonin

function.

Psychotherapy

The use of psychotherapeutic techniques of either a psychoana-lytic or a

supportive nature has not been proved successful in treating the specific

obsessions and compulsions that are a hall-mark of OCD. However, the more

characterological aspects that are part of obsessive–compulsive personality

disorder may be helped by a more psychoanalytically oriented approach. As noted

earlier, the defense mechanisms of reaction formation, isolation and undoing,

as well as a pervasive sense of doubt and need to be in control, are hallmarks

of the obsessive–compulsive char-acter. Salzman (1983) and MacKinnon and

Michels (1971) have written elegantly on how to approach the maladaptive

aspects of this character style in therapy. In essence, the patient must be

encouraged to take risks and learn to feel comfortable with, or at least less

anxious about, making mistakes and to accept anxiety as a natural and normal

part of human experience. Techniques for meeting such goals in treatment may

include the psychiatrist’s being relatively active in therapy to ensure that

the patient focuses on the present rather than getting lost in perfectly

recounting the past, as well as the psychiatrist’s being willing to take risks

and present herself or himself as less than perfect.

Neurosurgery

Occasionally, even after receiving adequate pharmacotherapy (including

augmentation), adequate behavioral therapy, and a combination of behavioral

therapy and pharmacotherapy, pa-tients may still experience intractable OCD

symptoms. Such patients may be candidates for neurosurgery. Although criteria

for who should receive neurosurgery vary, it has been suggested that failure to

respond to at least 5 years of systematic treatment is a reasonable criterion.

Frequently used criteria are the follow-ing: a minimum of two adequate

medication trials with augmen-tation plus adequate behavioral therapy in the

absence of severe personality disorder.

The procedures that have been most successful inter-rupt tracts involved

in the serotonin system. The surgical pro-cedures used – anterior capsulotomy,

cingulotomy and limbic leukotomy – all aim to interrupt the connection between

the cortex and the basal ganglia and related structures. Current stereotactic

surgical techniques involve the creation of precise lesions, which are often only

10 to 20 mm, to specific tracts. These procedures have often been done with

radiofrequency heated electrodes andmore recently, with gamma knife techniques.

Postsurgical risks have been minimized, and in some cases cognitive function

and personality traits improve along with symptoms of OCD.

Data compiled from a number of small studies have yielded success rates

of 25 to 84% with treatment. However, most samples are small, and the

procedures have often differed in both lesion location and size, making it difficult

to compare them. However, in a recent prospective long-term follow-up study,

all 44 patients received the same procedure (cingulotomy), although some had

single procedures and others multiple procedures (Dougherty et al., 2002). This study had several

important findings. Clinical improvement occurred in 32 to 45% of

patients, depending on the criteria used to rate full or partial response, and

the average effect size was 1.27, comparable to that seen in pharmacologic

trials (1.09–1.53). However, these changes were not immediately apparent

postoperatively, and most patients were encouraged to engage in pharmacotherapy

and/or behavior therapy postopera-tively. The longitudinal follow-up component

of the study, which was a mean duration of 32 months, allowed the researchers

to assess the longer-term impact of the procedure in ways other studies could

not. Of particular note, patients continued to show improvement for up to 29

months after surgery without receiving further procedures. As a result, the authors

noted that the typical 6-month wait before deciding whether to repeat and

extend the lesion may be too brief. In conclusion, neurosurgical treatments

offer hope to some of the most severely ill and treatment-resist-ant patients

and should therefore be considered. However, which surgical lesions are most

effective in which patients still needs much more study.

Related Topics