Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Course and Natural History

Course and Natural History

Age at Onset

Age at onset usually refers to the age when OCD symptoms (ob-sessions

and compulsions) reach a severity level wherein they lead to

impaired functioning or significant distress or are time-consuming (i.e., meet

DSM-IV criteria for the disorder). Reported age at onset is usually during late

adolescence. In one study drawn from an OCD clinic sample (N = 560), the onset for males

occurred significantly earlier than for females (19.5 ± 9.2 years versus 22.0 ± 9.8 years). In this study, 83%

of patients experi-enced the onset of significant symptoms between ages 10 and

24 years, whereas less than 15% experienced onset after age 35 years (Rasmussen

and Eisen, 1998). People with OCD, however, usu-ally describe the onset of

minor symptoms in childhood, well be-fore the onset of symptoms meeting full

criteria for the disorder.

In

several studies, earlier age at onset has been associated with an increased

rate of OCD in first-degree relatives and sug-gest that there is a familial

type of OCD characterized by early onset. Age at onset of OCD may also be a

predictor of course. The vast majority of patients report a gradual worsening

of obsessions and compulsions prior to the onset of full-criteria OCD, which is

followed by a chronic course (see later). However, Swedo and colleagues (1998)

have described a subtype of OCD that beginsbefore

puberty and is characterized by an episodic course with intense exacerbations.

Exacerbations of OCD symptoms in this subtype have been linked with Group A

beta-hemolytic strep-tococcal infections, which has led to the subtype

designation of pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with

streptococcal infections (PANDAS). In their study of 50 children with PANDAS,

the average age of onset was 7.4 years. Whether the course of illness in

patients with PANDAS continues to be episodic into adulthood, or, as is the

case with postpubertal on-set, tends to be chronic, is not known.

In

keeping with the older literature, a recent 2-year natu-ralistic prospective

study of 65 adults with OCD, in which the effect of treatment was assessed,

supported earlier findings that OCD is usually chronic with fluctuations in symptom

intensity but no lasting remission; it is notable that this course was most

common even during an era when effective treatments were avail-able. Although

50% of the subjects achieved partial remission in the first year of the study,

the probability of subsequent relapse was 48%. Only 12% achieved full and

sustained remission (Eisen et al., 1999). In contrast, a better outcome was found

in a follow-up study of 144 people with OCD assessed in the 1950s and again in

the 1990s (mean length of follow-up from illness onset was 47 years). Most

subjects reported a significant decrease in OCDsymptom

severity, which varied from complete recovery (20%), to recovery with continued

subclinical symptoms (28%), to con-tinued OCD but with clear improvement (35%).

Better outcome was associated with later age of onset and poorer social

function-ing at baseline (Skoog and Skoog, 1999).

In a prospective study of children with OCD, the major-ity (52%) of the

25 patients had moderate to severe OCD in the 2- to 7-year follow-up period

(Flament et al., 1990), which is

con-sistent with the data on adults. A more recent prospective study of 54 children

with OCD who were treated with clomipramine yielded a more hopeful picture of

OCD’s course. At 2 to 7 years after initial referral, 43 of these patients

still had symptoms that met criteria for OCD, but 73% were considered much or

very much improved, and 11% were completely asymptomatic (Leonard et al., 1993). This study suggested that

appropriate somatic treat-ment may improve outcome only while the patient

continues to receive this treatment (see later).

Phenomenology

OCD’s clinical presentation is characterized by phenomenological

subtypes based on the content of the obsessions and correspond-ing compulsions.

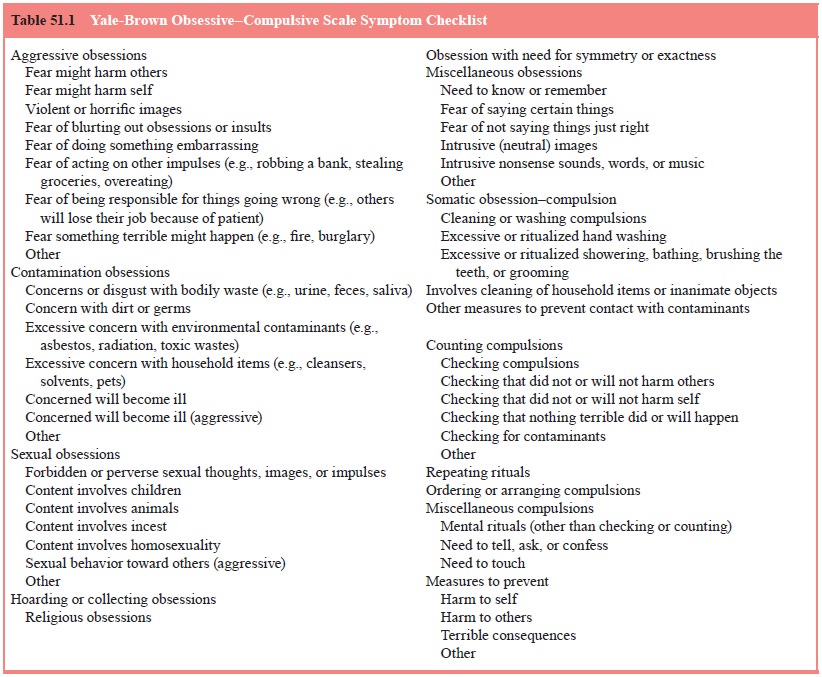

The list of subtypes in the Yale-Brown Obses-sive–Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS)

(Table 51.1) was generated on

the basis of clinical interviews with OCD patients in the 1980s. These

subtypes are remarkably consistent with phenomenologi-cal descriptions in the

psychiatric literature beginning with scru-pulosity in the 15th century.

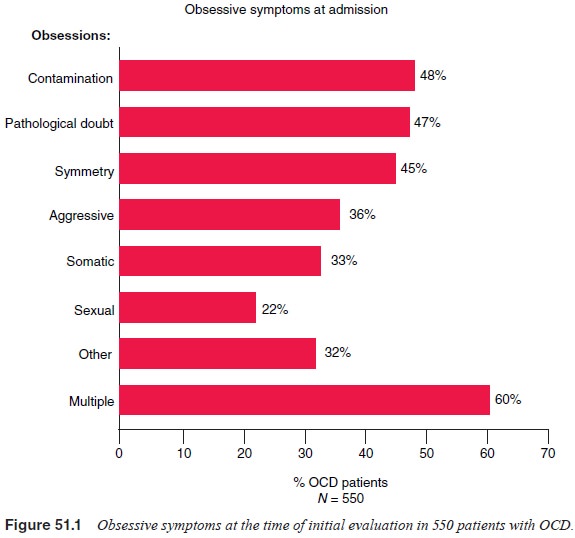

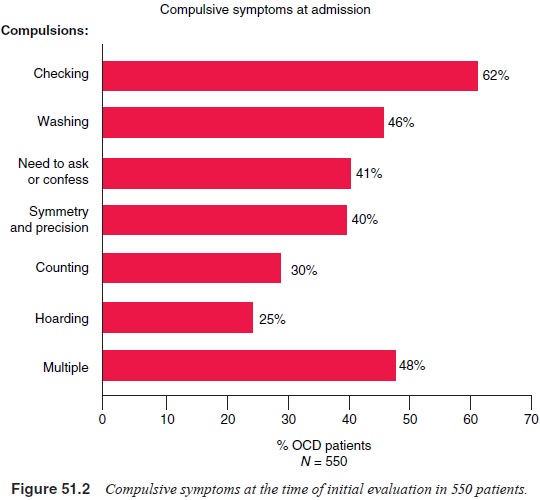

The basic types of obsessions and compulsions seem to be consistent

across cultures. The most common obsession is fear of contamination, followed

by pathological doubt, a need for symmetry and aggressive obsessions (Figure

51.1). The most common compulsion is checking, which is followed by washing,

symmetry, the need to ask or confess and counting (Figure 51.2). Children with

OCD present most commonly with washing com-pulsions, which are followed by

repeating rituals.

Most patients have multiple obsessions and compulsions over time, with a

particular fear or concern dominating the clini-cal picture at any one time.

The presence of obsessions without compulsions, or compulsions without

obsessions, is unusual. In the DSM-IV OCD field trial of 431 patients, only 2%

had pre-dominantly obsessions and 2% had predominantly compulsions; the

remaining 96% endorsed both obsessions and compulsions (Foa and Kozak, 1995).

Patients who appear to have obsessions without compulsions frequently have

unrecognized reassurance rituals or mental compulsions, such as repetitive,

ritualized pray-ing, in addition to their obsessions. Pure compulsions are also

unusual in adults, although they do occur in children, especially in the young

(e.g., 6 to 8 years of age). Most people have both mental and behavioral

compulsions; in the DSM-IV field trial 79.5% reported having both mental and

behavioral compulsions, 20.3% had behavioral compulsions only and 0.2% had only

men-tal compulsions.

The search for whether specific obsessions and compul-sions have

predictive value in terms of treatment response biologic markers, or genetic

transmission has not been particu-larly fruitful. There has been considerable

interest in exploring whether certain clusters of obsessions and compulsions

repre-sent specific OCD phenotypes. A number of studies have ad-dressed this

question systematically using the Y-BOCS Symp-tom Checklist to identify groups

of obsessions and compulsions that cluster together on factor analysis. Several

studies have found between three and five such symptom dimensions: sym-metry/ordering, hoarding,

contamination/cleaning, aggressive obsessions/checking and sexual/religious obsessions. The

sym-metry dimension has been associated with comorbid tic disor-der; in one

study, patients who scored high on this dimension had a relative risk for

chronic tic disorder that was 8.5 times higher than those scoring low on this

factor (Leckman et al., 1997). It

appears that these symptom dimensions are stable over time, that is, although a

patient’s specific obsessions and com-pulsions may change over time, new

obsessions and compul-sions that develop are often within the same symptom

dimen-sion as the previous symptoms. A study using positron emission tomography

to evaluate neural correlates of these symptom di-mensions suggests that dysfunction

in separate regions of the brain (e.g., striatum and prefrontal cortex) may

mediate these factors (Rauch et al.,

1998).

Data were analyzed from a number of placebo-controlled serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SRI) treatment studies to assess whether symptom factors or dimensions were associated with treatment response. No clear pattern emerged except that patients with hoarding obsession had a significantly poorer response to SRIs. Whether these identified dimensions are associated with response to behavioral treatment, biological markers, or genetic transmission has yet to be investigated.

The following descriptions of some common obsessions and compulsions

illustrate the clinical presentation of these symptoms. In some cases a

particular symptom may belong to more than one “type” of obsessive or

compulsive grouping. Thus it is often up to the clinician to decide which

category to place a symptom so that it best describes the patient’s symptoms

overall; it may even be best to classify it in more than one category. For

instance, a patient who has concerns about cancer may have handwashing as a

compulsion related to her somatic obsession. If this is the only reason that

she washes her hands, to avoid get-ting cancer, you might simply classify this

as a somatic obsession with the accompanying compulsion. However if the patient

also washes repeatedly to avoid contamination in general, not just for cancer,

she would have both contamination and somatic obses-sions and compulsions.

Related Topics