Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Treatment, Pharmacological Treatments, Assessing Treatment Resistance

Treatment

General Considerations

Both pharmacologic and behavioral therapies have proved effec-tive for

OCD. The majority of controlled treatment trials have been performed with

adults age 18 to 65 years. However, these therapies have been shown effective

for patients of all ages. In general, children and the elderly tolerate most of

these medi-cations well. For children, lower doses are indicated because of

lower body mass. For instance, the recommended dose for clomipramine in

children is up to 150 mg/day (3 mg/kg/day) versus 250 mg/day in adults. Use of

lower doses should also be considered in the elderly because their decreased

ability to metabolize medications can increase the risk of side effects and

toxicity. Behavioral therapy has also been used successfully in all age groups,

although when treating children with this mo-dality it is usually advisable to

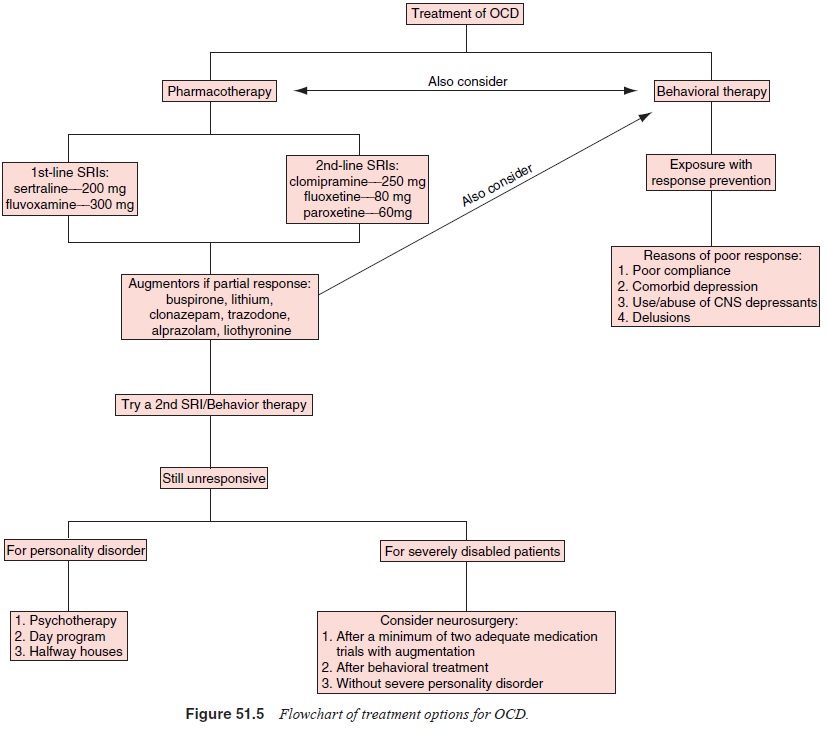

use a parent as a cotherapist. A flowchart that outlines treatment options for

OCD is shown in Figure 51.5

In general, the goals of treatment are to reduce the fre-quency and

intensity of symptoms as much as possible and to minimize the amount of

interference the symptoms cause. It should be noted that few patients

experience a cure or complete remission of symptoms. Instead, OCD should be

viewed as a chronic illness with a waxing and waning course. Symptoms are often

worse during times of psychosocial stress. Even when on medication, individuals

with OCD are often upset when they experience even a mild symptom exacerbation,

anticipating that their symptoms will revert to their worst, which is rarely

the case. Anticipating with the patient that stress may make the symptoms worse

can often be helpful in long-term treatment. Expert consensus guidelines, based

on completion of a survey by 79 experts in the field, provide a reasonable

approach to clini-cal practice in treating patients with OCD. However like any

consensus report, based on clinical practice, not all of the rec-ommendations

are supported by empirical data (March et

al., 1997). Further work in neurosurgical techniques, particularly less

invasive approaches like gamma knife and possibly trans-magnetic stimulation,

may offer other options in the future for treating OCD.

Pharmacological Treatments

The most extensively studied agents for OCD are medications that affect

the serotonin system. Many studies implicate the serotonin system in OCD’s

pathophysiology, although comparative studies also seem to implicate other

neurotransmitter systems, including the dopaminergic system, in treatment

response. The principal pharmacologic agents used to treat OCD are the SRIs,

which in-clude clomipramine, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, sertraline, paroxet-ine

and citalopram.

Outcome measures in OCD treatment trials generally in-clude the Yale-Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS; Goodman et al., 1989), a reliable and valid 10-item, 40-point semi-structured instrument that assesses the severity of obses-sions and rituals during the preceding week. Studies conducted since 1989 have generally used the Y-BOCS as one of the major outcome measures. Most studies have used Y-BOCS scores of 16 to 20 as a study entry criterion, although it has been argued that higher scores (e.g., 20–21) might reduce the increasing pla-cebo response rates being obtained in OCD studies. Treatment response is generally considered to constitute at least a 25 to 35% reduction in OCD symptoms as measured by the Y-BOCS. Another frequently used global outcome measure is the National Institute of Mental Health Global Obsessive–Compulsive Scale (NIMH-OC) (Pato et al., 1994).

Clomipramine

The tricyclic antidepressant clomipramine is among the most extensively

studied pharmacological agents in OCD. This drug is unique among the

antiobsessional agents in which in addition to its potency as an SRI, it has

significant affinity for noradren-ergic, dopaminergic, muscarinic and

histaminic receptors. The most common side effects are those typical of the tricyclic

anti-depressants, including dry mouth, dizziness, tremor, fatigue, somnolence,

constipation, nausea, increased sweating, head-ache, mental cloudiness and

sexual dysfunction. Previous data have indicated that at doses of 300 mg/day or

more, the risk of seizures is 2.1% but at doses of 250 mg/day or less, the risk

of seizures is low (0.48%) and comparable to that of other tri-cyclic

antidepressants. It is therefore recommended that doses of 250 mg/day or less

be used. Elderly patients may be more prone to tricyclic side effects, such as

orthostatic hypotension, constipation (which may lead to fecal impaction),

forgetfulness and mental cloudiness, which might be confused with dementia.

Most of these side effects can be treated by simply lowering the dose, although

the cardiac conduction effects of tricyclic anti- depressants may preclude the

use of clomipramine in patients with preexisting cardiac conduction problems,

especially atrio-ventricular block.

Recent studies of IV clomipramine have been par-ticularly promising

because it seems to have a quicker on-set of action and fewer side effects than

the oral form, and it may be effective even in patients who do not respond to

oral clomipramine. Oral clomipramine, like other SRIs, usu-ally takes a minimum

of 4 to 6 weeks to produce a clinically significant clinical response, but in

at least one study using IV pulse doses patients showed a response within 4.5

days. The reasons for this unique response are not fully understood, but it is

postulated that the IV preparation avoids first-pass hepatoenteric metabolism,

leading to increased bioavailabil-ity of the parent compound clomipramine. This

in turn may play a role in rapidly desensitizing serotonergic receptors or

initiating changes in postsynaptic serotonergic neurons. This preparation is

still not FDA-approved for clinical use in the USA. Cardiac monitoring is

recommended during the use of IV clomipramine.

Fluoxetine

Despite their different chemical structures, all of the SSRIs appear to

have similar efficacy in treating OCD. Fluoxetine has not been shown to be more

effective than clomipramine. The fixed-dose trials of fluoxetine are

particularly noteworthy because there are few published fixed-dose trials with

any of the antiobsessional agents in OCD. Although these studies indicated that

doses of 20, 40 and 60 mg/day were all effective when compared with pla-cebo,

there was a trend toward 60 mg/day being more effective. Some patients who did

not respond at lower doses responded at higher doses, and others who responded

at lower doses showed increased improvement at a higher dose. In addition,

patients maintained their improvement or experienced increased im-provement during

the 5- to 6-month follow-up period.

Fluoxetine has fewer side effects than clomipramine, re-flecting its

more selective mechanism of action. The most com-mon side effects are headache,

nausea, insomnia, anorexia, dry mouth, somnolence, nervousness, tremor and

diarrhea. Side ef-fects occur more frequently at higher doses. Fluoxetine’s

long half-life, which is unique among the SRIs, is 2 to 4 days for the parent

compound and 4 to 16 days for its active metabolite. This long half-life can be

beneficial for patients who do not comply with treatment, because relatively

high steady-state levels are maintained even when several doses are missed.

However, the long half-life can present problems when switching or

discon-tinuing fluoxetine, because 5 weeks or more may be required for the

medication to be completely cleared from the body. Hence the added delay, 5

weeks rather than 2 weeks for the other SRIs, is required when switching from

fluoxetine to an MAOI.

Fluvoxamine

Fluvoxamine is a unicyclic agent which differs from the other SSRIs in

that it does not have an active metabolite. A number of systematic blinded

clinical trials, most of which were placebo-controlled, have demonstrated

fluvoxamine’s effectiveness in treating OCD. As has been demonstrated for the

other SSRIs, relatively long treatment trials are indicated before concluding

that an SSRI is ineffective in OCD.

The largest and most recent fluvoxamine study was a 10-week multicenter

double-blind placebo-controlled study of 320 patients. The mean dose of

fluvoxamine was 249 mg/day. As in the other studies, the fluvoxamine-treated

patients had a sig-nificant reduction in OCD symptoms; however, unlike most of

the earlier medication trials there was a relatively high placebo response rate

of 11%. One of the important conclusions from this study was that prior failure

to respond to another SSRI was associated with a lower likelihood of responding

to fluvoxamine. All of the fluvoxamine studies show a similar side-effect

pro-file, which included insomnia, nervousness, fatigue, somnolence, nausea,

headache and sexual dysfunction. Insomnia and nerv-ousness tended to occur early

in treatment, whereas fatigue and somnolence occurred later. Overall, the

medication is well toler-ated, with only 10 to 15% of patients dropping out of

treatment because of side effects.

Sertraline

As is true of other studies, higher doses of sertraline 200 mg/day being

is more effective than 50 mg/day or 100 mg/day. Typical side effects included

nausea, headache, diarrhea, insomnia and dry mouth. A recent study compared

sertraline with the non-SRI antidepressant desipramine for patients with OCD and

co-morbid depression. Although these medications were similarlyefficacious for

depression, sertraline was more effective for OCD symptoms, supporting the use

of an SRI-like sertraline rather than a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor like

desipramine in such patients. In addition, even though desipramine did improve

depressive symptoms, a significantly greater number of patients treated with

sertraline achieved remission from depression (Hoehn-Saric et al., 2000).

Paroxetine

Paroxetine is another SSRI that differs in structure from those

previously discussed. It is a phenylpiperidine compound that is marketed as an

antidepressant and, like sertraline, shows promise in the treatment of OCD.

Results of a fixed-dose multicenter trial of 348 patients indicated that

paroxetine is effective for OCD. As was suggested in the sertraline study,

higher doses (40 or 60 mg/day) may be needed because 20 mg/day was no more

effec-tive than placebo (Wheadon et al.,

1993). Paroxetine’s efficacy is comparable to that of other SRIs, and side

effects are similar to those of other SSRIs and include lethargy, dry mouth,

nausea, insomnia, somnolence, tremor, sexual dysfunction and decreased

appetite. Reports of an acute discontinuation syndrome, which can include

general malaise, asthenia, dizziness, vertigo, head-ache, myalgia, loss of

appetite, nausea, diarrhea and abdominal cramps, warrant a gradual reduction in

dose if this medication is to be discontinued. Occasional patients may

experience some of these symptoms even if their dose is delayed by only a few

hours.

Citalopram

Citalopram is the newest SSRI available for the treatment of OCD and is

unique in its selectivity for serotonin reuptake com-pared with the other SRIs.

It has few significant secondary bind-ing properties, and its minimal effect on

hepatic metabolism probably makes it safer to combine with other medications. A

multicenter fixed-dose-placebo-controlled trial with 401 patients showed that

52 to 65% of patients responded in the three dosage groups compared with a 37%

response rate in the placebo group. While there was a trend for a higher dose

to lead to a higher re-sponse rate, as with other SRIs, there was no

statistical difference between the three doses used (20, 40 and 60 mg/day).

Typical side effects included fatigue, sweating, dry mouth, ejaculation

failure, nausea and insomnia, although many patients habituated to these side

effects in 4 to 6 weeks. Thus, citalopram is a good choice for OCD treatment

because of its side-effect profile and low probability of causing drug–drug

interactions (Montgomery et al.,

2001).

Other Agents

Most studies of other medications (venlafaxine, buspirone, trazo-adone,

clonazepam and MAOIs for OCD have consisted of only case reports or small

samples. However, few of these agents have been promising enough to warrant

large blinded efficacy trials.

Which SRI to Choose?

The efficacy of each SRI – clomipramine, fluoxetine, fluvoxam-ine,

sertraline, paroxetine, and citalopram – is supported by ex-isting data. During

the last 12 years at least seven head-to-head SRI comparison studies have been

done, six of which compared clomipramine with fluoxetine, fluvoxamine,

paroxetine and ser-traline. All of the studies found that the agents studied

were equally efficacious, although they may have been underpow-ered to detect

differences among medications. However, severalmeta-analyses of OCD trials,

which compared SRIs across large placebo-controlled multicenter trials, lend

some support to the notion that clomipramine might be more effective than the

more selective agents. These meta-analyses support a trial of clomi-pramine in

all patients who do not respond to SRIs, even though clomipiramine tends to

cause more side effects.

A number of studies have assessed predictors of medica-tion response.

Predictors of poor response include failure to re-spond to a previous SRI,

early age of OCD onset, presence of schizotypal personality disorder and

presence of hoarding. How-ever, not all studies have had consistent findings,

and more inves-tigation of this issues is needed using larger and more narrowly

defined samples.

It is worth noting that the SSRIs, via their effect on the liver

cytochrome system, can inhibit the metabolism of certain other drugs.

Fluoxetine can elevate blood levels of a variety of coadministered drugs,

including tricyclic antidepressants (such as clomipramine), carbamazepine,

phenytoin and trazodone. However, the other SSRIs (with the exception of

citalopram) can theoretically cause similar elevations, although fewer reports

on such interactions are currently available. Some clinicians have taken

advantage of these interactions by carefully combining flu-voxamine with

clomipramine in order to block clomipramine’s metabolism to

desmethylclomipramine; this in turn favors se-rotonin reuptake inhibition

provided by the parent compound rather than the norepinephrine reuptake

inhibition provided by the metabolite. However, caution should be used with

this ap-proach since the elevation in clomipramine levels, and perhaps other

compounds, can be nonlinear and quickly lead to danger-ous toxicity; at the

very least, clomipramine levels should be carefully monitored.

All of the SSRIs are generally well tolerated, with a rela-tively low

percentage of patients experiencing notable side ef-fects or discontinuing them

because of side effects. In addition, these compounds are unlikely to be lethal

in overdose, except for clomipramine, which can lead to cardiac arrhythmias and

death. All these agents can cause sexual side effects, ranging from anorgasmia

to difficulty with ejaculatory function. However, such symptoms are not readily

volunteered by the patient, thus it is important to ask. Should such symptoms

be experienced, conservative measures may include dosage reduction, transient

drug holidays for a special weekend or occasion, or switching to another SRI

since patients may not have the same degree of dysfunction with a different

agent. However if the clinician feels that it is critical to continue with same

agent, various treatments have been reported in the literature. Usually taken

within a few hours of sexual activity, no one agent has been shown to work

consistently. Among those that have been tried are yohimbine, buspirone,

cyproheptadine, buproprion, dextroamphetamine, methylphenidate, amantidine,

nefazodone, to name but a few.

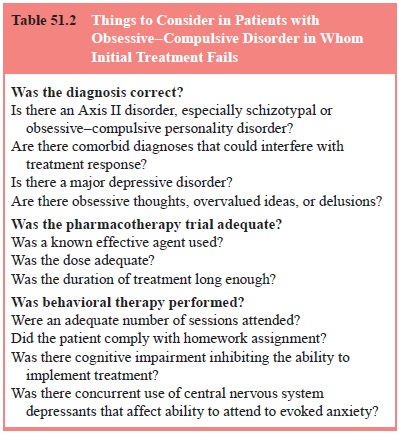

Assessing Treatment Resistance

Before concluding that a patient is treatment-resistant, the ad-equacy

of previous treatment trials must be assessed (see Table 51.2). In particular,

it is critical to know both the dura-tion and dose of every medication that has

been used. Typically, patients who appear treatment-resistant have received an

inad-equate duration of treatment, which should be a minimum of 10 to 12 weeks,

or an inadequate medication dose, which should be the maximum dose for any

particular agent. Some psychiatrists consider patients truly

treatment-resistant only if they have failed

several adequate pharmacologic trials, including one with clomi-pramine,

and several augmentation strategies including behav-ioral therapy. With this

kind of aggressive treatment, 80 to 90% of patients usually experience some

improvement, although few patients become symptom-free.

When inadequate treatment is not the reason for poor treatment response,

it is important to assess the accuracy of the diagnosis. Schizotypal

personality disorder, borderline personal-ity disorder, avoidant personality

disorder and OCPD seem to be associated with poorer response to

pharmacotherapy, particularly if the personality disorder is the primary

diagnosis. Behavioral therapy seems less effective in patients with comorbid

major de-pressive disorder. Comorbid depression may inhibit the ability to

learn and to habituate to anxiety. Initial pharmacotherapy some-times improves

depression, as well as OCD symptoms, and may increase the likelihood of success

with behavioral treatment.

Related Topics