Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Cerebrovascular Disorders

Nursing Process: The Patient Recovering from an Ischemic Stroke

NURSING PROCESS: THE PATIENT

RECOVERING FROM AN ISCHEMIC STROKE

The

acute phase of an ischemic stroke may last 1 to 3 days, but ongoing monitoring

of all body systems is essential as long as the patient requires care. The

patient who has had a stroke is at risk for multiple complications, including

deconditioning and other musculoskeletal problems, swallowing difficulties,

bowel and blad-der dysfunction, inability to perform self-care, and skin

break-down. After the stroke is complete, management focuses on the prompt

initiation of rehabilitation for any deficits.

Assessment

During

the acute phase, a neurologic flow sheet is maintained to provide data about

the following important measures of the patient’s clinical status:

·

Change in the level of

consciousness or responsiveness as ev-idenced by movement, resistance to

changes of position, and response to stimulation; orientation to time, place,

and person

·

Presence or absence of

voluntary or involuntary movements of the extremities; muscle tone; body

posture; and position of the head

·

Stiffness or flaccidity of the

neck

·

Eye opening, comparative size

of pupils and pupillary reac-tions to light, and ocular position

·

Color of the face and

extremities; temperature and moisture of the skin

·

Quality and rates of pulse and

respiration; arterial blood gas values as indicated, body temperature, and

arterial pressure

·

Ability to speak

·

Volume of fluids ingested or

administered; volume of urine excreted each 24 hours

·

Presence of bleeding

·

Maintenance of blood pressure

within the desired param-eters

After the acute phase, the nurse assesses mental

status (memory, attention span, perception, orientation, affect,

speech/language), sensation/perception (usually the patient has decreased

aware-ness of pain and temperature), motor control (upper and lower extremity

movement), swallowing ability, nutritional and hydra-tion status, skin

integrity, activity tolerance, and bowel and blad-der function. Ongoing nursing

assessment continues to focus on any impairment of function in the patient’s

daily activities, because the quality of life after stroke is closely related

to the patient’s functional status.

Diagnosis

NURSING DIAGNOSES

Based

on the assessment data, the major nursing diagnoses for a patient with a stroke

may include:

·

Impaired physical mobility

related to hemiparesis, loss of balance and coordination, spasticity, and brain

injury

·

Acute pain (painful shoulder)

related to hemiplegia and disuse

·

Self-care deficits (hygiene,

toileting, grooming, and feeding) related to stroke sequelae

·

Disturbed sensory perception

related to altered sensory re-ception, transmission, and/or integration

·

Impaired swallowing

·

Incontinence related to

flaccid bladder, detrusor instability, confusion, or difficulty in

communicating

·

Disturbed thought processes

related to brain damage, con-fusion, or inability to follow instructions

·

Impaired verbal communication

related to brain damage

·

Risk for impaired skin

integrity related to hemiparesis/ hemiplegia, or decreased mobility

·

Interrupted family processes

related to catastrophic illness and caregiving burdens

·

Sexual dysfunction related to

neurologic deficits or fear of failure

COLLABORATIVE PROBLEMS/ POTENTIAL COMPLICATIONS

Potential

complications include:

·

Decreased cerebral blood flow

due to increased ICP

·

Inadequate oxygen delivery to

the brain

·

Pneumonia

Planning and Goals

Although rehabilitation begins on the day the

patient has the stroke, the process is intensified during convalescence and

requires a coordinated team effort. It is helpful for the team to know whatthe

patient was like before the stroke: his or her illnesses, abilities, mental and

emotional state, behavioral characteristics, and activ-ities of daily living.

It is also helpful for clinicians to be knowl-edgeable about the relative

importance of predictors of stroke outcome (age, gender, NIHSS score at time of

admission, to name a few) in order to provide stroke survivors and their

families with realistic goals (Demchuk & Buchan, 2000).

The major goals for the patient (and family) may

include im-proved mobility, avoidance of shoulder pain, achievement of

self-care, relief of sensory and perceptual deprivation, prevention of

aspiration, continence of bowel and bladder, improved thought processes,

achieving a form of communication, maintaining skin integrity, restored family

functioning, improved sexual function, and absence of complications.

Nursing Interventions

Nursing care has a significant impact on the

patient’s recovery. Often many body systems are impaired as a result of the

stroke, and conscientious care and timely interventions can prevent

de-bilitating complications. During and after the acute phase, nurs-ing

interventions focus on the whole person. In addition to providing physical

care, nurses can encourage and foster recovery by listening to patients and

asking questions to elicit the mean-ing of the stroke experience (Eaves, 2000;

Pilkington, 1999).

IMPROVING MOBILITY AND PREVENTING JOINT DEFORMITIES

A

hemiplegic patient has unilateral paralysis (paralysis on one side). When

control of the voluntary muscles is lost, the strong flexor muscles exert

control over the extensors. The arm tends to adduct (adductor muscles are

stronger than abductors) and to ro-tate internally. The elbow and the wrist

tend to flex, the affected leg tends to rotate externally at the hip joint and

flex at the knee, and the foot at the ankle joint supinates and tends toward

plan-tar flexion.

Correct positioning is important to prevent

contractures; measures are used to relieve pressure, assist in maintaining good

body alignment, and prevent compressive neuropathies, especially of the ulnar

and peroneal nerves. Because flexor muscles are stronger than extensor muscles,

a posterior splint applied at night to the affected extremity may prevent

flexion and maintain correct po-sitioning during sleep.

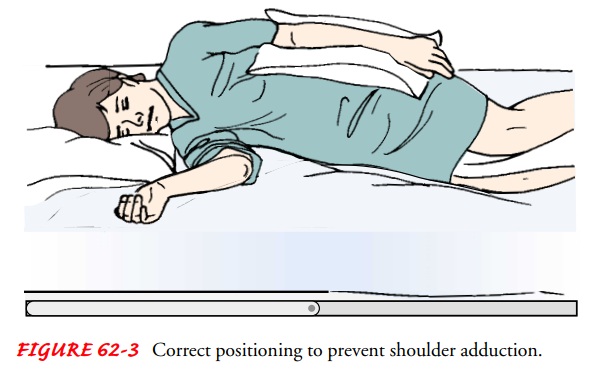

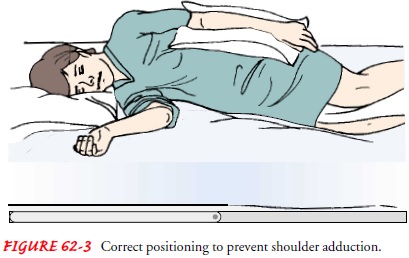

Preventing Shoulder Adduction

To

prevent adduction of the affected shoulder while the patient is in bed, a

pillow is placed in the axilla when there is limited ex-ternal rotation; this

keeps the arm away from the chest. A pillow is placed under the arm, and the

arm is placed in a neutral (slightly flexed) position, with distal joints

positioned higher than the more proximal joints. Thus, the elbow is positoned

higher than the shoulder and the wrist higher than the elbow. This helps to

prevent edema and the resultant joint fibrosis that will limit range of motion

if the patient regains control of the arm (Fig. 62-3).

Positioning the Hand and Fingers

The fingers are positioned so that they are barely flexed. The hand is placed in slight supination (palm faces upward), which is its most functional position. If the upper extremity is flaccid, a volar resting splint can be used to support the wrist and hand in a func-tional position. If the upper extremity is spastic, a hand roll is not used, because it stimulates the grasp reflex. In this instance a dorsal wrist splint is useful in allowing the palm to be free of pres-sure. Every effort is made to prevent hand edema.

Spasticity,

particularly in the hand, can be a disabling com-plication after stroke.

Researchers have recently reported that in-tramuscular injections of botulinum

toxin A decreased spasticity in the wrist and fingers and increased functional

ability in dress-ing, washing, and other activities of daily living (Brashear

et al., 2002).

Changing Positions

The

patient’s position should be changed every 2 hours. To place a patient in a

lateral (side-lying) position, a pillow is placed be-tween the legs before the

patient is turned. To promote venous return and prevent edema, the upper thigh

should not be acutely flexed. The patient may be turned from side to side, but

the amount of time spent on the affected side should be limited if sensation is

impaired.

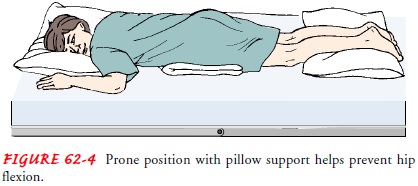

If

possible, the patient is placed in a prone position for 15 to 30 minutes

several times a day. A small pillow or a support is placed under the pelvis,

extending from the level of the umbili-cus to the upper third of the thigh

(Fig. 62-4). This helps to pro-mote hyperextension of the hip joints, which is

essential for normal gait and helps prevent knee and hip flexion contractures.

The prone position also helps to drain bronchial secretions and prevents

contractural deformities of the shoulders and knees. During positioning, it is

important to reduce pressure and change position frequently to prevent pressure

ulcers.

Establishing an Exercise Program

The affected extremities are exercised passively and put through a full range of motion four or five times a day to maintain joint mobility,

regain motor control, prevent contractures in the para-lyzed extremity, prevent

further deterioration of the neuro-muscular system, and enhance circulation.

Exercise is helpful in preventing venous stasis, which may predispose the

patient to thrombosis and pulmonary embolus.

Repetition

of an activity forms new pathways in the CNS and therefore encourages new

patterns of motion. At first, the ex-tremities are usually flaccid. If

tightness occurs in any area, the range-of-motion exercises should be performed

more frequently.

The

patient is observed for signs and symptoms that may in-dicate pulmonary embolus

or excessive cardiac workload during exercise; these include shortness of

breath, chest pain, cyanosis, and increasing pulse rate with exercise. Frequent

short periods of exercise always are preferable to longer periods at infrequent

in-tervals. Regularity in exercise is most important. Improvement in muscle

strength and maintenance of range of motion can be achieved only through daily

exercise.

The patient is encouraged and reminded to exercise

the un-affected side at intervals throughout the day. It is helpful to de-velop

a written schedule to remind the patient of the exercise activities. The nurse

supervises and supports the patient during these activities. The patient can be

taught to put the unaffected leg under the affected one to move it when turning

and exercis-ing. Flexibility, strengthening, coordination, endurance, and

bal-ancing exercises prepare the patient for ambulation. Quadriceps muscle

setting and gluteal setting exercises are started early to im-prove the muscle

strength needed for walking; these are per-formed at least five times daily for

10 minutes at a time.

Preparing for Ambulation

As

soon as possible, the patient is assisted out of bed. Usually, when hemiplegia

has resulted from a thrombosis, an active reha-bilitation program is started as

soon as the patient regains con-sciousness; a patient who has had a cerebral

hemorrhage cannot participate actively until all evidence of bleeding is gone.

The

patient is first taught to maintain balance while sitting and then to learn to

balance while standing. If the patient has dif-ficulty in achieving standing

balance, a tilt table, which slowly brings the patient to an upright position,

can be used. Tilt tables are especially helpful for patients who have been on

bed rest for prolonged periods and are having orthostatic blood pressure

changes.

If

the patient needs a wheelchair, the folding type with hand brakes is the most

practical because it allows the patient to ma-nipulate the chair. The chair

should be low enough to allow the patient to propel it with the uninvolved foot

and narrow enough to permit it to be used in the home. When the patient is

trans-ferred from the wheelchair, the brakes must be applied and locked on both

sides of the chair.

The

patient is usually ready to walk as soon as standing bal-ance is achieved.

Parallel bars are useful in these first efforts. A chair or wheelchair should

be readily available in case the patient suddenly becomes fatigued or feels

dizzy.

The training periods for ambulation should be short

and fre-quent. As the patient gains strength and confidence, an adjustable cane

can be used for support. Generally, a three- or four-pronged cane provides a

stable support in the early phases of rehabilitation.

PREVENTING SHOULDER PAIN

Up to 70% of stroke patients suffer severe pain in

the shoulder that prevents them from learning new skills, because shoulder

function is essential in achieving balance and performing transfers and

self-care activities. Three problems can occur: painful shoulder, subluxation

of the shoulder, and shoulder–hand syndrome.

A flaccid shoulder joint may be overstretched by

the use of ex-cessive force in turning the patient or from overstrenuous arm

and shoulder movement. To prevent shoulder pain, the nurse should never lift

the patient by the flaccid shoulder or pull on the affected arm or shoulder. If

the arm is paralyzed, subluxation (incomplete dislocation) at the shoulder can

occur from over-stretching the joint capsule and musculature by the force of

grav-ity when the patient sits or stands in the early stages after a stroke.

This results in severe pain. Shoulder–hand syndrome (painful shoulder and

generalized swelling of the hand) can cause a frozen shoulder and ultimately

atrophy of subcutaneous tissues. When a shoulder becomes stiff, it is usually

painful.

Medications are helpful in the management of

post-stroke pain. Amitriptyline hydrochloride (Elavil) has been used but it can

cause cognitive problems, has a sedating effect, and is not effective in all

patients. A recent study showed the efficacy of an antiseizure medication

lamotrigine (Lamictal) in treating post-stroke pain (Jensen et al., 2001).

Many shoulder problems can be prevented by proper

patient movement and positioning. The flaccid arm is positioned on a table or

with pillows while the patient is seated. Some clinicians advocate the use of a

properly worn sling when the patient first becomes ambulatory to prevent the

paralyzed upper extremity from dangling without support. Range-of-motion

exercises are important in preventing painful shoulder. Overstrenuous arm

movements are avoided. The patient is instructed to interlace the fingers,

place the palms together, and push the clasped hands slowly forward to bring

the scapulae forward; he or she then raises both hands above the head. This is

repeated throughout the day. The patient is instructed to flex the affected

wrist at intervals and move all the joints of the affected fingers. He or she

is encouraged to touch, stroke, rub, and look at both hands. Pushing the heel

of the hand firmly down on a surface is useful. Elevation of the arm and hand

is also important in preventing dependent edema of the hand. Patients with

continuing pain after movement and positioning have been attempted may require

the addition of analgesia to their treatment program.

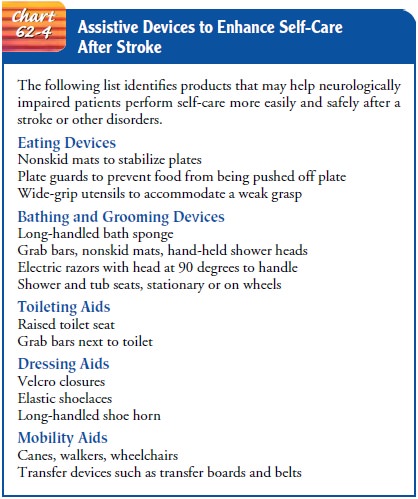

ENHANCING SELF-CARE

As soon as the patient can sit up, personal hygiene

activities are encouraged. The patient is helped to set realistic goals; if

feasible, a new task is added daily. The first step is to carry out all

self-care activities on the unaffected side. Such activities as combing the

hair, brushing the teeth, shaving with an electric razor, bathing, and eating

can be carried out with one hand and are suitable for self-care. Although the

patient may feel awkward at first, the var-ious motor skills can be learned by

repetition, and the unaffected side will become stronger with use. The nurse

must be sure that the patient does not neglect the affected side. Assistive

devices will help make up for some of the patient’s deficits (Chart 62-4). A

small towel is easier to control while drying after bathing, and boxed paper

tissues are easier to use than a roll of toilet tissue.

Return of functional ability is important to the patient recov-ering after a stroke. An early baseline assessment of functional ability with an instrument such as the Functional Independence Measure (FIM) is important in team planning and goal setting for the patient. The FIM is a widely used instrument in stroke re-habilitation and also provides valuable functional information during the acute phase of care (Hinkle, 2000, 2001).

The

patient’s morale will improve if ambulatory activities are carried out in

street clothes. The family is instructed to bring in clothing that is

preferably a size larger than that normally worn. Clothing fitted with front or

side fasteners or Velcro closures is the most suitable. The patient has better

balance if most of the dressing activities are done in a seated position.

Perceptual

problems may make it difficult for the patient to dress without assistance

because of an inability to match the clothing to the body parts. To assist the

patient, the nurse can take steps to keep the environment organized and

uncluttered, because the patient with a perceptual problem is easily

distracted. The clothing is placed on the affected side in the order in which

the garments are to be put on. Using a large mirror while dress-ing promotes

the patient’s awareness of what he or she is putting on the affected side. Each

garment is put on the affected side first. The patient has to make many

compensatory movements when dressing; these can produce fatigue and painful

twisting of the in-tercostal muscles. Support and encouragement are provided to

prevent the patient from becoming overly fatigued and discour-aged. Even with

intensive training, not all patients can achieve independence in dressing.

MANAGING SENSORY-PERCEPTUAL DIFFICULTIES

Patients

with a decreased field of vision should be approached on the side where visual

perception is intact. All visual stimuli (clock, calendar, and television)

should be placed on this side. The pa-tient can be taught to turn the head in

the direction of the defec-tive visual field to compensate for this loss. The

nurse should make eye contact with the patient and draw his or her attention to

the affected side by encouraging the patient to move the head. The nurse may

also want to stand at a position that encourages the patient to move or turn to

visualize who is in the room. Increasing the natural or artificial lighting in

the room and pro-viding eyeglasses are important in increasing vision.The

patient with homonymous hemianopsia (loss of half of the visual field) turns

away from the affected side of the body and tends to neglect that side and the

space on that side; this is called amorphosynthesis. In such instances, the

patient cannot see food on half of the tray, and only half of the room is

visible. It is im-portant for the nurse to constantly remind the patient of the

other side of the body, to maintain alignment of the extremities, and, if

possible, to place the extremities where the patient can see them.

MANAGING DYSPHAGIA

Stroke

can result in swallowing problems (dysphagia) due to im-paired function of the

mouth, tongue, palate, larynx, pharynx, or upper esophagus. Patients must be

observed for paroxysms of coughing, food dribbling out of or pooling in one

side of the mouth, food retained for long periods in the mouth, or nasal re-gurgitation

when swallowing liquids. Swallowing difficulties place the patient at risk for

aspiration, pneumonia, dehydration, and malnutrition.

A speech therapist will evaluate the patient’s gag

reflexes and ability to swallow. Even if partially impaired, swallowing

func-tion may return in some patients over time, or the patient may be taught

alternative swallowing techniques, advised to take smaller boluses of food, and

taught about which foods are easier to swal-low. The patient may initially be

started on a thick liquid or puréed diet because these foods are easier to

swallow than thin liquids. Having the patient sit upright, preferably out of

bed in a chair, and instructing him or her to tuck the chin toward the chest as

he or she swallows, will help prevent aspiration. The diet may be advanced as

the patient becomes more proficient at swal-lowing. If the patient cannot

resume oral intake, a gastrointesti-nal feeding tube will be placed for ongoing

tube feedings.

Managing Tube Feedings

Enteral tubes can be either nasogastric (placed in

the stomach) or nasoenteral (placed in the duodenum) to reduce the risk of

aspi-ration. Nursing responsibilities in feeding include elevating the head of

the bed at least 30 degrees to prevent aspiration, check-ing the position of

the tube before feeding, ensuring that the cuff of the tracheostomy tube (if in

place) is inflated, and giving the tube feeding slowly. The feeding tube is

aspirated periodically to ensure that the feedings are passing through the

gastrointestinal tract. Retained or residual feedings increase the risk for

aspiration. Patients with retained feedings may benefit from the placement of a

gastrostomy tube or a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube. In a patient

with a nasogastric tube, the feeding tube should be placed in the duodenum to

reduce the risk of aspiration. For long-term feedings, a gastrostomy tube is

preferred.

ATTAINING BOWEL AND BLADDER CONTROL

After a stroke, the patient may have transient

urinary inconti-nence due to confusion, inability to communicate needs, and

in-ability to use the urinal or bedpan because of impaired motor and postural

control. Occasionally after a stroke, the bladder becomes atonic, with impaired

sensation in response to bladder filling. Sometimes control of the external

urinary sphincter is lost or di-minished. During this period, intermittent

catheterization with sterile technique is carried out. When muscle tone

increases and deep tendon reflexes return, bladder tone increases and

spasticity of the bladder may develop. Because the patient’s sense of

aware-ness is clouded, persistent urinary incontinence or urinary reten-tion

may be symptomatic of bilateral brain damage. The voiding pattern is analyzed

and the urinal or bedpan offered on this pat-tern or schedule. The upright

posture and standing position are helpful for male patients during this aspect

of rehabilitation.

Patients

may also have problems with bowel control or con-stipation, with constipation

being more common. Unless con-traindicated, a high-fiber diet and adequate

fluid intake (2 to 3 L per day) should be provided and a regular time

established (usu-ally after breakfast) for toileting.

IMPROVING THOUGHT PROCESSES

After

a stroke, the patient may have problems with cognitive, be-havioral, and emotional

deficits related to brain damage. In many instances, however, a considerable

degree of function can be re-covered because not all areas of the brain are

equally damaged; some remain more intact and functional than others.

After

assessment that delineates the patient’s deficits, the neu-ropsychologist, in

collaboration with the primary care physician, psychiatrist, nurse, and other

professionals, structures a training program using cognitive-perceptual

retraining, visual imagery, reality orientation, and cueing procedures to

compensate for losses.

The

role of the nurse is supportive. The nurse reviews the results of

neuropsychological testing, observes the patient’s per-formance and progress,

gives positive feedback, and, most impor-tantly, conveys an attitude of

confidence and hope. Interventions capitalize on the patient’s strengths and

remaining abilities while attempting to improve performance of affected

functions. Other interventions are similar to those for improving cognitive

func-tioning after a head injury.

IMPROVING COMMUNICATION

Aphasia,

which impairs the patient’s ability to understand what is being said and to

express himself or herself, may become ap-parent in various ways. The cortical

area responsible for integrat-ing the myriad of pathways required for the

comprehension and formulation of language is called Broca’s area. It is located

in a convolution adjoining the middle cerebral artery. This area is

re-sponsible for control of the combinations of muscular move-ments needed to

speak each word. Broca’s area is so close to the left motor area that a

disturbance in the motor area often affects the speech area. This is why so

many patients paralyzed on the right side (due to damage or injury to the left

side of the brain) cannot speak, whereas those paralyzed on the left side are

less likely to have speech disturbances.

The

speech pathologist assesses the communication needs of the stroke patient,

describes the precise deficit, and suggests the best overall method of

communication. With many language in-tervention strategies for the aphasic

adult, the program can be in-dividually tailored. The patient is expected to

take an active part in establishing goals.

A

person with aphasia may become depressed because of the inability to talk. The

inability to talk on the telephone, answer a question, or participate in

conversation causes anger, frustration, fear of the future, and hopelessness.

Nursing interventions in-clude doing everything possible to make the atmosphere

con-ducive to communication. This includes being sensitive to the patient’s

reactions and needs and responding to them in an ap-propriate manner, always

treating the patient as an adult. The nurse provides strong moral support and

understanding to allay anxiety.

A

common pitfall is for the nurse or other health care team member to complete

the thoughts or sentences of the patient.This should be avoided because it may

cause the patient to feel more frustrated at not being allowed to speak and may

deter ef-forts to practice putting thoughts together and completing the

sentence. A consistent schedule, routines, and repetitions help the patient to

function despite significant deficits. A written copy of the daily schedule, a

folder of personal information (birth date, address, names of relatives),

checklists, and an audiotaped list help improve the patient’s memory and

concentration. The pa-tient may also benefit from a communication board, which

has pictures of common needs and phrases. The board may be trans-lated into

several languages.

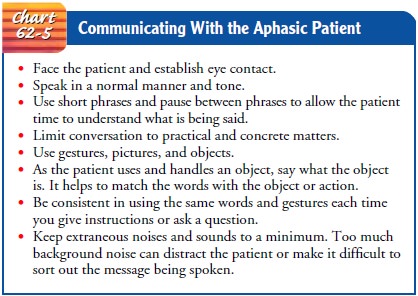

When

talking with the patient, it is important to have the pa-tient’s attention,

speak slowly, and keep the language of instruc-tion consistent. One instruction

is given at a time, and time is allowed for the patient to process what has

been said. The use of gestures may enhance comprehension. Speaking is thinking

out loud, and the emphasis is on thinking. The patient must sort out incoming

messages and formulate a response. Listening requires mental effort; the

patient must struggle against mental inertia and needs time to organize an

answer.

In

working with the aphasic patient, the nurse must remem-ber to talk to the

patient during care activities. This provides so-cial contact for the patient.

Chart 62-5 describes points to keep in mind when communicating with the aphasic

patient.

MAINTAINING SKIN INTEGRITY

The stroke patient may be at risk for skin and

tissue breakdown because of altered sensation and inability to respond to

pressure and discomfort by turning and moving. Therefore, preventing skin and

tissue breakdown requires frequent assessment of the skin, with emphasis on

bony areas and dependent parts of the body. During the acute phase, a specialty

bed (eg, low-air-loss bed) may be used until the patient can move independently

or as-sist in moving.

A regular turning and positioning schedule must be followed to minimize pressure and prevent skin breakdown. Pressure-relieving devices may be employed but do not replace regular turn-ing and positioning. The turning schedule (at least every 2 hours) must be adhered to even if pressure-relieving devices are used to prevent tissue and skin breakdown. When the patient is posi-tioned or turned, care must be used to minimize shear and friction forces, which cause damage to tissues and predispose the skin to breakdown.

The patient’s skin must be kept clean and dry;

gentle massage of healthy (nonreddened) skin and adequate nutrition are other

factors that help to maintain normal skin and tissue integrity.

IMPROVING FAMILY COPING

Family

members play an important role in the patient’s recovery. Some type of

counseling and support system should be available to them to prevent the care

of the patient from taking a signifi-cant toll on their health and interfering

too radically with their lives. Involving others in the patient’s care and

teaching stress management techniques and methods for maintaining personal

health also facilitate family coping.

The

family may have difficulty accepting the patient’s disabil-ity and may be

unrealistic in their expectations. They are given information about the

expected outcomes and are counseled to avoid doing for the patient those things

that he or she can do. They are assured that their love and interest are part

of the pa-tient’s therapy.

The

family needs to be informed that the rehabilitation of the hemiplegic patient

requires many months; progress may be slow. The gains made by the patient in

the hospital or rehabilitation unit must be maintained. All should approach the

patient with a supportive and optimistic attitude, focusing on the abilities

that remain. The rehabilitation team, the medical and nursing team, the

patient, and the family all must be involved in developing at-tainable goals

for the patient at home.

Most

relatives of stroke patients handle the physical changes better than the

emotional aspects of care. The family should be prepared to expect occasional

episodes of emotional lability. The patient may laugh or cry easily and may be

irritable and de-manding or depressed and confused. The nurse can explain to

the family that the patient’s laughter does not necessarily connote happiness,

nor does crying reflect sadness, and that emotional la-bility usually improves

with time.

HELPING THE PATIENT COPE WITH SEXUAL DYSFUNCTION

Sexual functioning can be profoundly altered by

stroke. Often stroke is such a catastrophic illness that the patient

experiences loss of self-esteem and value as a sexual being. Although research

in this area of stroke management is limited, it appears that stroke patients

consider sexual function to be important, but most have sexual dysfunction. The

combined effects of age and stroke cause a marked decline in many aspects of

sexuality (Lipski & Alexan-der, 1997). In-depth assessments to determine sexual

history be-fore and after the stroke should be followed by appropriate

interventions. Interventions for the patient and partner focus on providing

relevant information, education, reassurance, adjust-ment of medications,

counseling regarding coping skills, sugges-tions for alternative positions, and

a means of sexual expression and satisfaction (Lipski & Alexander, 1997).

PROMOTING HOME AND COMMUNITY-BASED CARE

Teaching Patients Self-Care

Patient and family education is a fundamental

component of re-habilitation, and ample opportunity for learning about stroke,

its causes and prevention, and the rehabilitation process should be provided

(Mumma, 2001). In both acute care and rehabilitation facilities, the focus is

on teaching patients to resume as much self-care as possible. This may entail

using assistive devices or modifying the home environment to help the patient

live with a disability.

An

occupational therapist may be helpful in assessing the home environment and

recommending modifications to help the patient become more independent. For

example, a shower is more convenient than a tub for the hemiplegic patient

because most patients do not gain sufficient strength to get up and down from a

tub. Sitting on a stool of medium height with rubber suc-tion tips permits the

patient to wash with greater ease. A long-handled bath brush with a soap

container is helpful to the patient who has only one functional hand. If a

shower is not available, a stool may be placed in the tub and a portable shower

hose at-tached to the faucet. Handrails may be attached beside the bath-tub and

the toilet. Other assistive devices include special utensils for eating,

grooming, and dressing (see Chart 62-3).

Continuing Care

The

recovery and rehabilitation process after stroke may be pro-longed, requiring

patience and perseverance on the part of the pa-tient and family. Depending on

the specific neurologic deficits resulting from the stroke, the patient at home

may require the ser-vices of a number of health care professionals. The nurse

often coordinates the care of the patient at home. The family (often the

spouse) will require assistance in planning and providing care. The caregiver

often requires reminders to attend to his or her health problems and

well-being.

The

family is advised that the patient may tire easily, become irritable and upset

by small events, and is likely to show less in-terest in things. Because a

stroke frequently occurs in the later stages of life, there is the possibility

of intellectual decline related to dementia.

Emotional

problems associated with stroke are often related to speech dysfunction and

frustrations about being unable to communicate. A speech therapist who visits

the home allows the family to be involved and gives the family practical

instructions to help the patient between therapy sessions.

Depression is a common and serious problem in the

stroke pa-tient. Antidepressant therapy may help if depression dominates the

patient’s life. As progress is made in the rehabilitation program, some

problems will diminish. The family can help by continuing to support the

patient and by giving positive reinforcement for the progress that is being

made.

Community-based stroke support groups allow the

patient and family to learn from others with similar problems and to share

their experiences (Olson, 2001). The patient is encouraged to continue with

hobbies, recreational and leisure interests, and contact with friends to

prevent social isolation. All nurses com-ing in contact with the patient should

encourage the patient to keep active, adhere to the exercise program, and

remain as self-sufficient as possible.

The nurse should recognize the potential effects of

caregiving on the family (Teel et al., 2001). Not all families have the

adap-tive coping skills and psychological functioning necessary for the

long-term care of another. The patient’s spouse may be elderly, with his or her

own health problems; in some instances the stroke patient may have been the

provider of care to the spouse. Even healthy caregivers may find it difficult

to maintain a schedule that includes being available around the clock. Some

effects of sus-tained caregiving include increased risk for depression and

sub-stance abuse, and increased use of health care services by the caregiver

(King et al., 2001). Depressed caregivers are more likely to resort to physical

or emotional abuse of the patient and are more likely to place the patient in a

nursing home. Respite care(planned short-term care to relieve the family from

having to pro-vide continuous 24-hour care) may be available from an adult day

care center. Some hospitals also offer weekend respite care that can provide

caregivers with needed time to themselves. Nurses should encourage families to

arrange for such services and should provide information to assist them.

The nurse involved in home and continuing care also needs to remind patients and family members of the need for continuing health promotion and screening practices. Patients who have not been involved in these practices in the past are educated about their importance and are referred to appropriate health care providers, if indicated.

Evaluation

EXPECTED PATIENT OUTCOMES

Expected

patient outcomes may include:

1) Achieves

improved mobility

a) Avoids

deformities (contractures and footdrop)

b) Participates

in prescribed exercise program

c) Achieves

sitting balance

d) Uses

unaffected side to compensate for loss of function of hemiplegic side

2) Reports

absence of shoulder pain

a) Demonstrates

shoulder mobility; exercises shoulder

b) Elevates

arm and hand at intervals

3) Achieves

self-care; performs hygiene care; uses adaptive equipment

4) Turns

head to see people or objects

5) Demonstrates

improved swallowing ability

6) Achieves

normal bowel and bladder elimination

7) Participates

in cognitive improvement program

8) Demonstrates

improved communication

9) Maintains

intact skin without breakdown

a) Demonstrates

normal skin turgor

b) Participates

in turning and positioning activities

10) Family

members demonstrate a positive attitude and cop-ing mechanisms

a) Encourage

patient in exercise program

b) Take

an active part in rehabilitation process

c) Contact

respite care programs or arrange for other fam-ily members to assume some

responsibilities for care

11) Has

positive attitude regarding alternative approaches to sexual expression

Related Topics