Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Medication-induced Movement Disorders

Neuroleptic-induced tardive dyskinesia

Neuroleptic-induced

tardive dyskinesia

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Neuroleptic-induced

tardive dyskinesia (TD) is a syndrome con-sisting of abnormal, involuntary

movements caused by long-term treatment with antipsychotic medication. The

movements are typically choreoathetoid in nature and principally involve the

mouth, face, limbs and trunk. TD, by definition, occurs late in the course of

drug treatment. It is likely that a number of separate neurotransmitter systems

are involved in the pathogenesis of TD. There may be different subtypes of TD,

each perhaps involving a unique profile of neurochemical imbalance.

Neuroleptic-induced striatal pathological change represents another possibility

for ex-plaining mechanisms of TD and some have suggested that long-term

antipsychotic use may produce “toxic free radicals” that damage neurons and

result in persistent TD.

Epidemiology and Comorbidity

The

reported prevalence of TD has been somewhat variable as a result of differences

in populations of patients and in the methods used. Yassa and Jeste (1992)

reviewed 76 studies of the preva-lence of TD published from 1960 to 1990. In a

total population of approximately 40 000 patients, the overall prevalence of TD

was 24.2%, although it was much higher (about 50%) in studies of elderly

patients treated with antipsychotics.

There

have been relatively few studies of the incidence of TD. Kane and coworkers

(1988) prospectively studied more than 850 patients (mean age 29 years) and

found the incidence of TD after cumulative exposure to conventional

antipsychotics to be 5% after 1 year, 18.5% after 4 years and 40% after 8

years. In-cidence in older populations has been found to be much higher. Saltz

and colleagues (1991) reported an incidence of 31% after 43 weeks of

conventional antipsychotic treatment in a popula-tion of elderly patients.

Jeste and colleagues (1999) evaluated 439 psychiatric patients with a mean age

of 65 years and found that 28.8% of the sample met criteria for TD during the

first 12 months of study treatment; 50.1% had TD by the end of 24 months; and

63.1% by the end of 36 months. The risk of severe TD has also been reported to

be higher in older patients.

Evidence

supporting a reduced risk of TD with atypical an-tipsychotics is beginning to

emerge. The lower risk of EPS with atypical agents has led to the widespread

conclusion that these agents will also have reduced TD risk. The low risk of

tardive dyskinesia in clozapine-treated individuals has been well estab-lished.

In addition, a lower incidence of TD has been reported in patients treated with

risperidone and olanzapine. More long-term prospective studies are needed with

the atypical agents.

Aging

consistently appears to be the most important risk factor for the development

of TD. Prevalence and severity of TD seem to increase with age. The reasons for

this increased risk of TD with aging are not known but may be related to the

propen-sity of the nigrostriatal system to degenerate with age as well as

pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic factors.

Gender (female) was thought to be a risk factor for TD. A meta-analysis of the published reports demonstrated a greater prevalence of TD in women (26.6%) compared with that in men (21.6%) (Yassa and Jeste, 1992). Interestingly, studies of in-cidence of TD in older patients failed to confirm the reported propensity of women to have TD at a higher rate than men. A possible relationship between gender and age of onset of schizo-phrenia to severity of dyskinesia has been reported as women with late-onset schizophrenia (LOS) and men with early-onset schizophrenia (EOS) had more severe dyskinesia than men with LOS and women with EOS.

There are

conflicting reports regarding ethnicity as a risk factor for TD and people with

diabetes mellitus may be at a higher risk for development of TD. Some have

proposed that diabetes mellitus might be a risk factor for TD in patients

treated with metoclopramide.

Patients

who experience an acute neuroleptic-induced movement disorder (especially

parkinsonism or akathisia) are likely to be at a greater risk for development

of TD if antipsychotic treatment is continued. Total exposure to typical

antipsychotic agents has been correlated with TD risk and within elderly

pop-ulations, cumulative amount of typical antipsychotics has also been

associated with TD risk, especially with high-potency con-ventional agents. The

observation that anticholinergic drugs ex-acerbate some symptoms of TD does not

appear to indicate that the drugs promote the onset of the disorder.

Assessment and Differential Diagnosis

TD may

develop at any age and typically has an insidious on-set. It may develop during

exposure to antipsychotic medication or within 4 weeks of withdrawal from an

oral antipsychotic (or within 8 weeks of withdrawal from a depot neuroleptic).

There must be a history of at least 3 months of antipsychotic use (or 1 month in

the elderly) before TD may be diagnosed (American Psychiatric Association,

2000).

The most

common features of TD are involuntary move-ments of the tongue, face and neck

muscles. Less common are movements in the upper and lower extremities as well

as in the trunk. Most rare of all are involuntary movements of the mus-cle

groups involved with breathing and swallowing. The earliest symptoms typically

involve buccolingual–masticatory move-ments. The movements of TD are choreiform

(rapid, jerky), athetoid (slow, sinuous), or rhythmical (stereotypical)

(American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

Severe

choreoathetoid dyskinesia differs from the milder forms, mainly in the

frequency and amplitude of the abnormal movements. Some cases of severe

dyskinesia consist of general-ized choreoathetosis of the face, trunk and all

four limbs. TD may be accompanied by dystonias, parkinsonism and akathisia. TD

is worsened by stimulants, short-term withdrawal of antipsychotic medication,

anticholinergic medication, emotional arousal, stress and voluntary movements

of other parts of the body. It is im-proved by relaxation, voluntary movements

of the involved parts of the body, sleep and increased dose of antipsychotics.

The

differential diagnosis of TD is extensive. The major task for the psychiatrist

is to rule out other causes of dyskinesia. It may be useful for the

psychiatrist to keep in mind three ques-tions for the facilitation of the

differential diagnosis: 1) Does the patient have dyskinesia? 2) Does another

disorder fully explain the cause of the dyskinesia? 3) If the dyskinesia is

related to an-tipsychotic use, is it TD?

A number

of nondyskinetic movement disorders are part of the differential diagnosis of

TD. Tremor can be confused with TD, including the tremor of neuroleptic-induced

parkinsonism, rabbit syndrome, Wilson’s disease and cerebellar disease.

Fur-ther, fine tremors of the fingers and hands are produced by anxi-ety

states, alcoholism, hyperthyroidism and drugs. Acute dysto-nias, myoclonus,

tics, mannerisms, compulsions and akathisia must be differentiated from TD. The

differentiation is made on the basis of the clinical assessment.

Once it

has been established that the patient suffers from a dyskinesia, the main cause

must be determined. In children and young adults, a number of conditions may

cause dyskinesia be-sides antipsychotic treatment. The use of drugs, especially

am-phetamines and antihistamines, are associated with dyskinesia. Sydenham’s

chorea can produce choreiform movements. Con-version disorder and malingering

are conditions that can present with apparently involuntary movements.

Hyperthyroidism and hypoparathyroidism are two endocrinological conditions that

can produce dyskinesias similar to TD. Huntington’s disease is a condition that

can be difficult to distinguish clinically from TD, but certain characteristics

may aid in the diagnosis, including 1) afamily history of Huntington’s disease,

2) the presence of demen-tia, 3) a slowly progressive downhill course, and 4)

atrophy of the caudate nucleus on computed tomography scan.

In the

middle-aged or elderly patient, denture or dental problems may commonly mimic

TD. Lesions of the basal ganglia may result in dyskinesias. The use of

antiparkinsonian medica-tions such as levodopa, amantadine and bromocriptine

can cause dyskinetic movements. The presence of spontaneous dyskinesias must

also be ruled out.

When it

has been established that antipsychotics are re-sponsible for the dyskinesia,

it does not follow that the dyskinesia is necessarily TD. Acute dyskinesia

occurring early in antipsy-chotic treatment is common and responds well to

antihistaminic or anticholinergic medications. Withdrawal–emergent dyskinesia

also occurs in a variable proportion of patients. This phenomenon refers to the

appearance or worsening of dyskinetic movements on reduction or discontinuation

of antipsychotic medication. Withdrawal–emergent dyskinesia is

phenomenologically similar to TD and often has the full range of involuntary

choreiform and athetoid movements. A typical case may begin within a few days

after a sudden decrease in dosage and worsen as the antipsychotic is withdrawn.

This phase is followed by rapid improvement in a period of weeks to months. A

history of antipsychotic exposure and remission of dyskinetic symptoms within 3

months of an-tipsychotic withdrawal are suggestive of the diagnosis of

with-drawal–emergent dyskinesia.

Finally,

tardive Tourette’s disorder must be differentiated from TD. A number of cases

of tardive Tourette’s disorder have been reported as a result of treatment with

antipsychotics, emerg-ing during treatment or after cessation of treatment.

Tardive Tourette’s disorder presents with symptoms similar to those of

idiopathic Tourette’s disorder. Motor tics are usually compulsive organized stereotypies

that may, in certain cases, be difficult to distinguish from the choreoathetoid

movements of TD. Typically, vocal tics (including barks, grunts, coughs and

yelps) represent part of tardive Tourette’s disorder but not TD. Tardive

Tourette’s disorder seems to show a pharmacological response similar to that of

TD, leading to the assumption that the syndrome may be a type of the more

commonly seen TD. Thus, tardive Tourette’s disorder may be masked by an

increase in antipsychotics and ex-acerbated by withdrawal.

Course

One-third

of the TD patients experience remission within 3 months of discontinuation of

antipsychotic medication, and approximately half have remission within 12 to 18

months of antipsychotic discontinuation (American Psychiatric Associa-tion,

2000). Elderly patients are reported to have lower rates of remission,

especially if antipsychotics are continued. When TD patients must be maintained

with antipsychotics, TD seems to be stable in 50%, worsen in 25% and improve in

the rest. Time may be the most important factor in outcome of TD. In studies

that have followed up patients for longer than 5 years, TD seems to improve in

half of patients with or without antipsychotic treat-ment. Furthermore, TD may

improve as slowly as it develops and may exist on a spectrum between resolution

and persistence.

Severe TD

may lead to numerous physical complications and psychosocial problems. Dental

and denture problems are common sequelae of severe oral dyskinesia as are

ulcerations of the tongue, cheeks and lips. Hyperkinetic dysarthria has been

described. Swallowing disorders represent another complica-tion. Respiratory

disturbances, although fairly rare, have been reported by a number of

investigators. These disturbances are usually manifested by shortness of breath

at rest, irregularities in respiration, and various grunts, snorts and gasps.

Respira-tory alkalosis may be seen on laboratory tests. Gastrointestinal

complications of severe TD may involve vomiting and dysphagia secondary to

disruption of the normal activity of the esophagus; weight loss may result from

such a disturbance.

Subjective

distress is a common accompaniment of severe dyskinesia. Suicidal ideation may

result from distress over the dyskinesia, and there have been reports of some successful

sui-cides. General impairment of functioning may be related to the severity of

the dyskinetic disorder. Social embarrassment as a result of TD may represent a

reason that some patients with TD tend to be reluctant to leave their homes.

Even mild dyskinesia may lead to anxiety, guilt, shame and anger. These

symptoms can lead to severe depressive episodes.

Treatment

Despite

intense effort, there is as yet no consistently reliable therapy for TD. As a

result, the psychiatrist must focus primary efforts toward prevention of the

disorder. The use of atypical antipsychotics are recommended due to their

probable lower risk of TD. Antipsychotic use should be minimized in all

pa-tients. Patients with nonpsychotic mood or other disorders who need antipsychotics

should receive the minimal necessary amounts of antipsychotic treatment and

should have the medica-tion tapered and then stopped once the clinical need is

no longer present. In general, there must be enough clinical evidence to show

that the benefits outweigh the potential risks of TD devel-opment.

Antipsychotics should be used with particular caution in elderly patients

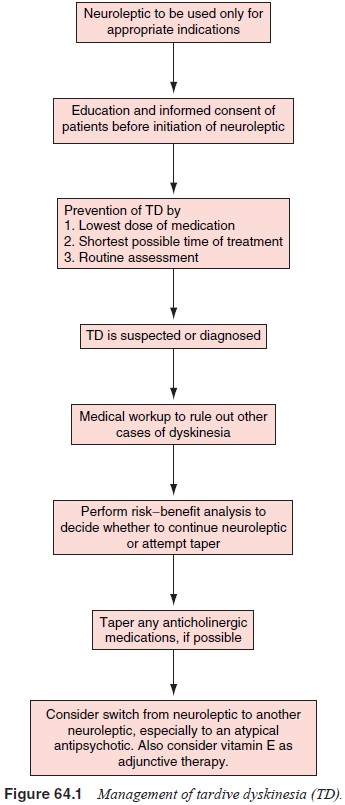

because of their high risk for development of TD (Figure 64.1).

Gradual

taper of the antipsychotic medication may be at-tempted as long as the

risk/benefit ratio of antipsychotic main-tenance versus withdrawal does not

preclude such a strategy. A slow taper of medication to the lowest effective

dose is probably the preferred strategy for the treatment of chronic

schizophrenia in a large number of stable patients.

Paradoxically,

antipsychotics themselves represent the most effective short-term treatment for

TD. An increase in dos-age of a conventional agent usually (approximately 66%

of pa-tients) results in a clinically significant but temporary reduction in TD

symptoms.The most exciting development in the treatment of TD has been the use

of the atypical antipsychotics. Clozapine has been shown to be effective in

reducing TD in patients with existing TD, however, side effects such as

agranulocytosis and clozapine’s affinity for anticholinergic side effects

limits its use. Additional studies have noted a beneficial effect of other

atypical agents (i.e., risperidone and olanzapine) on preexisting TD. The

reduced risk of TD with all atypical agents (when used at ap-propriate doses)

supports their use as preventive measures and as therapeutic options for those

who develop TD on a conventional antipsychotic.

A number

of experimental studies have attempted to treat TD with alternative strategies.

One treatment that has demonstrated some efficacy has been the use of vitamin

alpha-tocopherol. If antipsychotic treatment results in the production of free radicals that damage the neuronal components, an antioxidant such as vitamin E would therefore, theoretically, result in improvement in the symptoms of TD. Vitamin E is a possible agent for the treatment and prophylaxis of TD. A number of studies of varying design have shown benefit of vitamin E in TD however, a recent double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter trial failed to show a difference between vitamin E and placebo after 1 year of treatment (Adler et al., 1999). Although the results are far from conclusive, vitamin E remains a reasonably safe treatment modality for a patient with recently diagnosed TD. Doses are usually in the range of 1200 to 1600 mg/day. Other agents have been investigated, such as calcium channel blockers (i.e., diltiazem, verapamil, nifedipine) and clonazepam, but more studies are warranted.

Psychiatrists

must regularly assess for the presence and progression of TD and present the

patient (or the patient’s guardian, when appropriate) with information about

the risks of treatment; they may also give written information sheets, assess

understanding by the patient or guardian, and accu-rately record evidence of

the informed consent in the patient’s record.

Related Topics