Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Medication-induced Movement Disorders

Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome

Neuroleptic

Malignant Syndrome

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Neuroleptic

Malignant Syndrome (NMS) is a potentially fatal reaction to antipsychotic

medications that is characterized clini-cally by muscle rigidity, fever,

autonomic instability and changes in level of consciousness. The

pathophysiological mechanism of NMS remains unclear. The hypothesis of most

interest is that of reduced dopaminergic activity secondary to

neuroleptic-induced dopamine blockade. This reduced dopamine activity in

differ-ent parts of the brain (hypothalamus, nigrostriatal system and

corticolimbic tracts) may serve to explain the various clinical features of

NMS. Dopamine reduction in the hypothalamus may cause fever and autonomic

instability; in the nigrostriatal system, dopamine reduction may lead to the

rigidity; and the reduction in corticolimbic dopamine activity may explain the

altered con-sciousness. This hypothesis is based on the fact that

antipsychot-ics are dopamine-blocking agents, whereas certain dopamine agonists

are reported to help resolve NMS.

The

dopaminergic blocking theory does not, however, ex-plain why NMS may develop at

a given time and in a given pa-tient. There are probably other genetic

(possibly a predisposition similar to that seen in malignant hyperthermia),

constitutional, environmental, and pharmacological factors that interact to

pro-duce the syndrome. A number of investigators have proposed that other

neurotransmitter abnormalities may be responsible for the syndrome, including

serotonergic hyperfunction in the hypotha-lamus, excessive catecholamine

secretion, and gamma-aminobu-tyric acid deficiency.

Epidemiology and Comorbidity

The exact

frequency of NMS is unknown. A number of retrospec-tive and prospective studies

have found 0.02 to 3.2% of patients treated with antipsychotics to be affected

with NMS. Several factors probably account for this large variability in

frequency, including differences in study methods and diagnostic criteria for

NMS. A prior episode of NMS appears to predispose to future episodes of NMS.

Any preexisting medical problems, especially those associated with agitation or

dehydration, may increase the likelihood of NMS development when antipsychotics

are used. Patients with a neurological condition as well as patients with

presumed psychosis due to human immunodeficiency virus in-fection may be at

higher risk for development of NMS. A number of potential risk factors related

to antipsychotic treatment have been identified. Higher doses of antipsychotic,

rapid increases in dosage (especially “rapid neuroleptization”) and

intramuscular injections of high-potency conventional agents (e.g., haloperidol

and fluphenazine) have been reported to be risk factors for NMS. NMS can occur

(but rarely) in patients prescribed atypical an-tipsychotics and a review of

atypical-induced NMS concluded that symptoms appear similar to NMS induced by

conventional antipsychotics.

NMS is

more frequently reported in men than in women and is more frequently seen in a

younger population. A previous diagnosis of a mood disorder may place patients

at a higher risk for NMS. Warm, humid climates may also predispose to the

dis-order (American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

Assessment and Differential Diagnosis

NMS

usually presents in the first month of antipsychotic treat-ment but may develop

at any time. Two-thirds of the cases mani-fest within the first week of

treatment (American Psychiatri

Association,

2000). The two key diagnostic features for the dis-order are severe muscle

rigidity (classically referred to as lead pipe rigidity) and elevated

temperature. A number of other fea-tures are also seen (see DSM-IV-TR

criteria). For the psychiatrist, the most suggestive features are fluctuating

consciousness (from confusion to coma), labile vital signs (tachycardia,

unstable or elevated blood pressure), laboratory evidence of muscle injury

(elevation of creatine kinase) and leukocytosis. Other features include

diaphoresis, dysphagia, tremor, incontinence and mutism (American Psychiatric

Association, 2000).

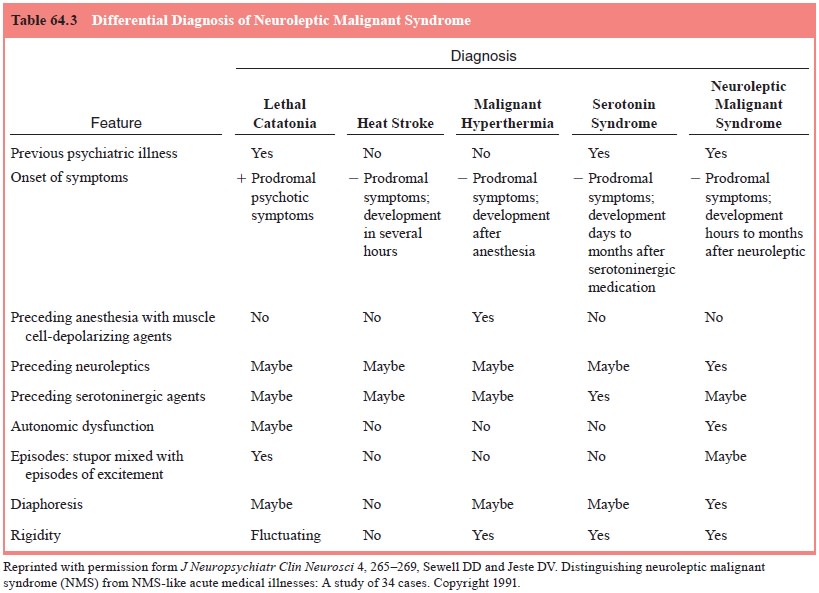

The

differential diagnosis of NMS can be difficult (Table 64.3). The most important

point is that the psychiatrist must start by suspecting NMS and then carefully

rule out other possible organic problems. Because medical illness is a likely

predisposing factor, it is important to consider that NMS may be present even

if a definitive organic disease is found to explain the NMS-like symptoms.

Numerous

general medical and neurological conditions can present with symptoms that may

resemble NMS. Examples include central nervous system infection, status

epilepticus, subcortical brain lesions, porphyria and tetanus (American

Psychiatric Associ-ation, 2000). The presence of significantly elevated

temperature and severe muscle rigidity makes the diagnosis of NMS more likely.

The

syndrome of lethal catatonia (seen in patients with uncontrolled manic

excitement or catatonic schizophrenia) can mimic NMS (with increased

temperature, autonomic irregu-larities and elevated creatine kinase), and the

differential di-agnosis can be difficult. It is obviously important to

determine whether the patient is indeed being treated with an antipsychotic. Although

NMS may clinically look like catatonia, NMS does not typically have alternating

periods of catatonic excitement and catatonic mutism. A past history of

catatonic episodes is also im-portant in making the differential diagnosis.

Lorazepam may be useful in alleviating the symptoms of catatonia but it has not

been shown to be useful in treatment of NMS. Therefore, it is possible that a

brief lorazepam trial could provide a useful and relatively easy method of

distinguishing between these two conditions. The problem, of course, is that

not all cases of catatonia respond to lorazepam.

Heat

stroke may also look like NMS but typically differs in that it presents with

hypotension, dry skin and limb flaccid-ity (American Psychiatric Association,

2000). Malignant hyper-thermia can also have a similar presentation but

generally occurs within the context of a patient’s receiving halogenated

anesthetic agents or succinylcholine. This condition typically begins

im-mediately after administration of the anesthetic agent and only in

genetically susceptible individuals (American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

Medications

can cause a number of conditions that may present as syndromes similar to NMS.

Allergic drug reactionsmay produce fever and autonomic instability but not

rigidity. Se-rotonin syndrome, with common clinical characteristics includ-ing

fever, resting tremor, rigidity, myoclonus and generalized seizures should also

be considered. A medication history can usually help distinguish between the

two syndromes, but patients receiving antipsychotics may also be treated with

selective sero-tonin reuptake inhibitors, thus making the clinical picture more

confusing. Lithium intoxication and anticholinergic delirium can both resemble

NMS, as can intoxication with amphetamines, co-caine and phencyclidine as well

as rapid termination of antipar-kinsonian medication.

Course

The

course of NMS is variable. Some cases may progress to fatal-ity, whereas others

may follow a mild self-limited course. Once the syndrome is recognized and the

antipsychotic medication is discontinued, the syndrome usually resolves between

2 weeks and 1 month (American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

Mortality

rate is reported to be 4 to 25%. The most com-mon medical complications leading

to morbidity and mortality are respiratory failure and renal failure. Shalev

and coworkers (1989) reported that myoglobinemia and renal failure are the best

predictors of mortality in NMS; the presence of either condition imparted a 50%

mortality risk. In general, complications are a result of physiologic

consequences of severe rigidity and immo-bilization such as deep vein

thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, dehydration and an increased risk for

rhabdomyolysis.

Treatment

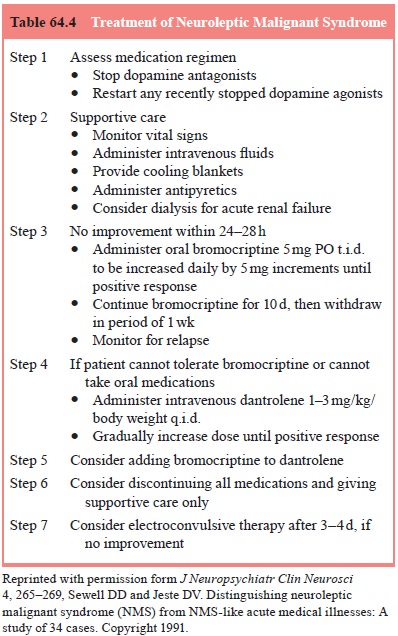

The most

critical step in treatment (Table 64.4) is to recognize the clinical features

of the syndrome and rapidly discontinue the an-tipsychotic. The importance of

this initial step mandates that psy-chiatrists who use antipsychotics in their

practice be cognizant of the early clinical features and recognize that the

syndrome can occur at any time during the course of treatment. Once the

an-tipsychotic has been stopped, supportive care remains the core of treatment

and often must be carried out in the context of a medical intensive care unit.

Each supportive intervention should be targeted to a specific symptom. Examples

of interventions in-clude cooling blankets for fever, cardiac monitoring for

arrhyth-mias, parenteral hydration for dehydration and monitoring for urine

output and renal function. Dialysis may also be considered for acute renal

failure.

It should

be noted that despite their widespread use, the efficacy of the muscle relaxant

dantrolene and the dopamine agonist bromocriptine has not been thoroughly

established. Electroconvulsive therapy is another treatment option in NMS

presumably because it increases dopamine turnover in the brain.

Electroconvulsive therapy is particularly indicated when there is difficulty in

distinguishing between NMS and lethal catatonia and when there seems to be a

significant risk of recurrence of NMS on restarting neuroleptics. Some

psychiatrists report rapid

and

dramatic success in the use of electroconvulsive therapy for NMS.

At

present, the appropriate course is to begin with antipsy-chotic discontinuation

and supportive care and to consider anti-dote therapy only if improvement in

symptoms is not seen within the first few days. The treatment of NMS should be

individual-ized for each patient based on clinical signs and symptoms. For example,

supportive care may be sufficient in mild and early cases of NMS. Trials of

bromocriptine, dantrolene, or amantadine are suggested for patients with

moderate symptoms. Anticholiner-gics can be used in managing afebrile patients

with neuroleptic-induced parkinsonian symptoms and benzodiazepines may be

useful for agitation in NMS. ECT is recommended in situations where lethal

catatonia is suspected, when NMS symptoms are treatment refractory, and in

patients who remain psychotic in the immediate post-NMS period.

A

particular difficulty for the psychotic patient who has NMS is that rechallenge

with antipsychotics may cause NMS to recur. Successful rechallenge seems to be

positively related to the length of time elapsed after resolution of NMS. There

is some evidence to suggest that clozapine may have relatively little

propensity to induce NMS. Clozapine, therefore, may represent one option for

the patient who has experienced NMS with a con-ventional agent. It is likely

but not yet known definitively that atypical antipsychotics will prove to have

a lower frequency of NMS. In general, it is recommended to switch to an agent

in a different chemical class and with a lower D2 affinity compared

with the causal agent.

Related Topics