Chapter: Software Testing : Controlling and Monitoring

Measurements and milestones for controlling and monitoring

Measurements and milestones for

controlling and monitoring

All

processes should have measurements (metrics) associated with them. The

measurements help to answer questions about status and quality of the process,

as well as the products that result from its implementation. Measurements in

the testing domain can help to track test progress, evaluate the quality of the

software product, manage risks, classify and prevent defects, evaluate test

effectiveness, and determine when to stop testing. Level 4 of the TMM calls for

a formal test measurement program. However, to establish a baseline process, to

put a monitoring program into place, and to evaluate improvement efforts, an

organization needs to define, collect, and use measurements starting at the

lower levels of the TMM.

To begin

the collection of meaningful measurements each organization should answer the

following questions:

• Which

measures should we collect?

• What is

their purpose (what kinds of questions can they answer)?

• Who will

collect them?

• Which

forms and tools will be used to collect the data?

• Who will

analyze the data?

• Who to

have access to reports?

When

these question have been addressed, an organization can start to collect simple

measurements beginning at TMM level 1 and continue to add measurements as their

test process evolves to support test process evaluation and improvement and

process and product quality growth. In this chapter we are mainly concerned

with monitoring and controlling of the testing process as defined in Section

9.0, so we will confine ourselves to discussing measurements that are useful

for this purpose. Chapter 11 will provide an in-depth discussion of how to

develop a full-scale measurement program applicable to testing. Readers will

learn how measurements support test process improvement and product quality

goals.

The following

sections describe a collection of measurements that support monitoring of test

over time. Each measurement is shown in italics to highlight it. It is

recommended that measurements followed by an asterisk (*) be collected by all

organizations, even those atTMMlevel 1. The reader should note that it is not

suggested that all of the measurements listed be collected by an organization.

TheTMMlevel, and the testing goals that an organization is targeting, affect

the appropriateness of these measures. As a simple example, if a certain degree

of branch coverage is not a testing objective for a organization at this time,

then this type of measurement is not relevant. However, the organization should

strive to include such goals in their test polices and plans in the future.

Readers familiar with software metrics concepts should note that most of the

measures listed in this chapter are mainly process measures; a few are product

measures. Other categories for the measures listed here are (i) explicit, those

that are measured directly from the process or product itself, and (ii)

derived, those that are a result of the combination of explicit and/or other

derived measures. Note that the ratios described are derived measures.

Now we

will address the question of how a testing process can be monitored for each

project. A test manager needs to start with a test plan. What the manager wants

to measure and evaluate is the actual work that was done and compare it to work

that was planned. To help support this goal, the test plan must contain testing

milestones as described in Chapter 7.

Milestones are tangible events that are expected to

occur at a certain time in the project’s lifetime. Managers use them to

determine project status.

Test

milestones can be used to monitor the progress of the testing efforts

associated with a software project. They serve as guideposts or goals that need

to be meet. A test manger uses current testing effort data to determine how

close the testing team is to achieving the milestone of interest. Milestones

usually appear in the scheduling component of the test plan (see Chapter 7).

Each level of testing will have its own specific milestones. Some examples of

testing milestones are:

• completion

of the master test plan;

• completion

of branch coverage for all units (unit test);

• implementation

and testing of test harnesses for needed integration of major subsystems;

• execution

of all planned system tests;

• completion

of the test summary report.

Each of

these events will be scheduled for completion during a certain time period in

the test plan. Usually a group of test team members is responsible for

achieving the milestone on time and within budget. Note that the determination

of whether a milestone has been reached depends on availability of measurement

data. For example, to make the above milestones useful and meaningful testers

would need to have measurements in place such as:

• degree of

branch coverage accomplished so far;

• number of

planned system tests currently available;

• number of

executed system tests at this date.

Test

planners need to be sure that milestones selected are meaningful for the

project, and that completion conditions for milestone tasks are not too

ambiguous. For example, a milestone that states ―unit test is completed when

all the units are ready for integration‖ is too

vague to use for monitoring progress. How can a test manager evaluate the

condition, ―ready‖? Because

of this ambiguous completion condition, a test manager will have difficulty

determining whether the milestone has been reached. During the monitoring

process measurements are collected that relates to the status of testing tasks

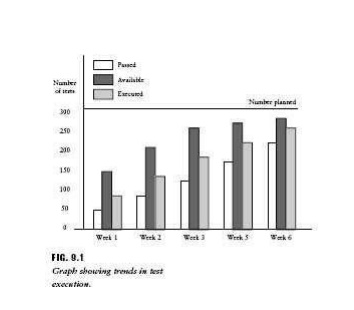

(as described in the test plan), and milestones. Graphs using test process data

are developed to show trends over a selected time period. The time period can

be days, weeks, or months depending on the activity being monitored. The graphs

can be in

the form

of a bar graph as shown in Figure 9.1 which illustrates trends for test

execution over a 6-week period. They can also be presented in the form of x,y plots where the y-axis would be the number of tests and the x-axis would be the weeks elapsed from the start of the testing

process for the project. These graphs, based on current measurements, are

presented at the weekly status meetings and/or at milestone reviews that are

used to discuss progress. At the status meetings, project and test leaders

present up-to-date measurements, graphs and plots showing the status of testing

efforts.

Testing

milestones met/not met and problems that have occurred are discussed. Test

logs, test incident reports, and other test-related documents may be examined

as needed. Managers will have questions about the progress of the test effort.

Mostly, they will want to know if testing is proceeding according to schedules

and budgets, and if not, what are the barriers. Some of the typical questions a

manager might ask at a status meeting are:

Have all

the test cases been developed that were planned for this date?

• What

percent of the requirements/features have been tested so far?

• How far

have we proceeded on achieving coverage goals: Are we ahead or behind what we

scheduled?

• How many

defects/KLOC have been detected at this time?Howmany repaired? How many are of

high severity?

• What is

the earned value so far? Is it close to what was planned (see Section 9.1.3)?

• How many

available test cases have been executed? How many of these were passed?

•

How much of the allocated testing budget has been

spent so far? Is it more or less than we estimated?

How productive

is tester X? How many test cases has she developed? How many has she run? Was

she over, or under, the planned amount?

The

measurement data collected helps to answer these questions. In fact, links

between measurements and question are described in the Goals/ Questions/Metrics

(GQM) paradigm reported by Basili [2]. In the case of testing, a major goal is to monitor and control testing

efforts (a maturity goal at TMM level 3). An organizational team

(developers/testers, SQA staff, project/test managers) constructs a set of

likely questions that test/project

managers are likely to ask in order to monitor and control the testing process.

The sample set of questions previously described is a good starting point.

Finally, the team needs to identify a set of measurements that can help to answer these questions. A sample set

of measures is provided in the following sections. Any organizational team can

use them as a starting point for selecting measures that help to answer

testrelated monitoring and controlling questions. Four key items are

recommended to test managers for monitoring and controlling the test efforts

for a project. These are:

(i) testing

status;

(ii)

tester productivity;

(iii)testing

costs;

(iv)errors, faults, and failures.

In the

next sections we will examine the measurements required to track these items.

Keep in mind that for most of these measurements the test planner should

specify a planned value for the measure in the test plan. During test the

actual value will be measured during a specific time period, and the two then

compared.

Measurements for Monitoring Testing Status

Monitoring

testing status means identifying the current state of the testing process. The

manager needs to determine if the testing tasks are being completed on time and

within budget. Given the current state of the testing effort some of the

questions under consideration by a project or test manager would be the

following:

• Which

tasks are on time?

• Which

have been completed earlier then scheduled, and by how much?

• Which are

behind schedule, and by how much?

• Have the

scheduled milestones for this date been meet?

• Which

milestones are behind schedule, and by how much?

The

following set of measures will help to answer these questions. The test status

measures are partitioned into four categories as shown in Figure 9.2. A test

plan must be in place that describes, for example, planned coverage goals, the

number of planned test cases, the number of requirements to be tested, and so

on, to allow the manager to compare actual measured values to those expected

for a given time period.

1. Coverage Measures

As test

efforts progress, the test manager will want to determine how much coverage has

been actually achieved during execution of the tests, and how does it compare

to planned coverage. Depending on coverage goals for white box testing, a

combination of the following are recommended.

Degree of statement, branch, data

flow, basis path, etc., coverage (planned, actual)* Tools can support the gathering of this

data. Testers can also use ratios such as:

Actual degree of coverage/planned degree of

coverage to monitor coverage to date. For black

box coverage the following measures can be useful:

Number of requirements or features to be tested* Number of equivalence classes identified

Number of equivalence classes actually covered

Number or degree of requirements or features

actually covered*

Testers

can also set up ratios during testing such as:

Number of features actually covered/total number of

features*

This will

give indication of the work completed to this date and the work that still

needs to be done.

Test Case Development

The

following measures are useful to monitor the progress of test case development,

and can be applied to all levels of testing. Note that some are explicit and

some are derived. The number of

estimated

test cases described in the master test plan is:

Number of planned test cases

The

number of test cases that are complete and are ready for execution is:

Number of available test cases

In many

cases new test cases may have to be developed in addition to those that are

planned. For example, when coverage goals are not meet by the current tests,

additional tests will have to be designed. If mutation testing is used, then

results of this type of testing may require additional tests to kill the

mutants. Changes in requirements could add new test cases to those that were

planned. The measure relevant here is:

Number of unplanned test cases

In place

of, or in addition to, test cases, a measure of the number planned, available,

and unplanned test procedures is often used by many organizations to monitor

test status.

Test Execution

As

testers carry out test executions, the test manager will want to determine if

the execution

process is

going occurring to

plan. This next

group of measures

is appropriate.

Number of available test cases executed*

Number of available tests cases executed and passed*

Number of unplanned test cases executed

Number of unplanned test cases executed and passed.

For a new

release where there is going to be regression testing then these are useful:

Number of planned regression tests executed

Number of planned regression tests executed and

passed

Testers

can also set up ratios to help with monitoring test execution. For example:

Number of available test cases executed/number of

available test cases

Number of available test cases executed/number of

available test cases executed and passed

These

would be derived measures.

Test Harness Development

It is

important for the test manager to monitor the progress of the development of

the test harness code needed for unit and integration test so that these

progress in a timely manner according to the test schedule. Some useful

measurements are:

Lines of Code (LOC) for the test harnesses (planned,

available)*

Size is a

measure that is usually applied by managers to help estimate the amount of

effort needed to develop a software system. Size is measured in many different

ways, for example, lines of code, function points, and feature points. Whatever

the size measure an organization uses to measure its code, it can be also be

applied to measure the size of the test harness, and to estimate the effort

required to develop it. We use lines of code in the measurements listed above

as it is the most common size metric and can be easily applied to estimating

the size of a test harness. Ratios such as:

Available LOC for the test harness code/planned LOC

for the test harnesses are useful to monitor the test harness development effort over time.

Measurements to Monitor Tester Productivity

Managers

have an interest in learning about the productivity of their staff, and how it

changes as the project progresses. Measuring productivity in the software

development domain is a difficult task since developers are involved in many

activities, many of which are complex, and not all are readily measured. In the

past the measure LOC/hour has been used to evaluate productivity for

developers. But since most developers engage in a variety of activities, the

use of this measure for productivity is often not credible. Productivity

measures for testers have been sparsely reported. The following represent some

useful and basic measures to collect for support in test planning and

monitoring the activities of testers throughout the project. They can help a

test manger learn how a tester distributes his time over various testing

activities. For each developer/tester, where relevant, we measure both planned

and actual:

Time spent in test planning

Time spent in test case design* Time spent in test

execution* Time spent in test reporting Number of test cases developed*

Number of test cases executed*

Productivity

for a tester could be estimated by a combination of:

Number of test cases developed/unit time* Number of

tests executed/unit time*

Number of LOC test harness developed/unit time*

Number of defects detected in testing/unit time

The last

item could be viewed as an indication of testing efficiency. This measure could

be partitioned for defects found/hour in each of the testing phases to enable a

manager to evaluate the efficiency of defect detection for each tester in each

of these activities. For example:

Number of defects detected in unit test/hour

Number of defects detected in integration

test/hour, etc.

The relative

effectiveness of a tester in each of these testing activities could be

determined by using ratios of these measurements. Marks suggests as a tester

productivity measure [3]:

Number of test cases produced/week

All of

the above could be monitored over the duration of the testing effort for each

tester. Managers should use these values with caution because a good measure of

testing productivity has yet to be identified. Two other comments about these

measures are:

1.

Testers perform a variety of tasks in addition to designing and running test

cases and developing test harnesses. Other activities such as test planning,

completing documents, working on quality and process issues also consume their

time, and those must be taken into account when productivity is being

considered.

2.

Testers should be aware that measurements are being gathered based on their

work, and they should know what the measurements will be used for. This is one

of the cardinal issues in implementing a measurement program. All involved

parties must understand the purpose of collecting the data and its ultimate

use.

Measurements for

Monitoring Testing Costs

Besides

tracking project schedules, recall that managers also monitor costs to see if

they are being held within budget. One good technique that project managers use

for budget and resource monitoring is called earned value tracking. This

technique can also be applied to monitor the use of resources in testing. Test

planners must first estimate the total number of hours or budget dollar amount

to be devoted to testing. Each testing task is then assigned a value based on

its estimated percentage of the total time or budgeted dollars. This gives a

relative value to each testing task, with respect to the entire testing effort.

That value is credited only when the task is completed. For example, if the

testing effort is estimated to require 200 hours, a 20-hour testing task is

given a value of 20/200*100 or 10%. When that task is completed it contributes

10% to the cumulative earned value of the total testing effort. Partially

completed tasks are not given any credit. Earned values are usual presented in

a tabular format or as a graph. An example will be given in the next section of

this chapter. The graphs and tables are useful to present at weekly test status

meetings.

To

calculate planned earned values we need the following measurement data:

Total estimated time or budget for the overall

testing effort

Estimated time or budget for each testing task

Earned

values can be calculated separately for each level of testing. This would

facilitate monitoring the budget/resource usage for each individual testing

phase (unit, integration, etc.). We want to compare the above measures to:

Actual cost/time for each testing task*

We also

want to calculate:

Earned value for testing tasks to date

and

compare that to the planned earned value for a specific date. Section 9.2 shows

an earned value tracking form and contains a discussion of how to apply earned

values to test tracking. Other measures useful for monitoring costs such as the

number of planned/actual test procedures (test cases) are also useful for

tracking costs if the planner has a good handle on the relationship

between

these numbers and costs (see Chapter 7). Finally, the ratio of:

Estimated costs for testing/Actual costs for

testing can be applied to a series of releases or related projects to evaluate and promote more accurate test cost

estimation and higher test cost effectiveness through test process improvement.

Measurements for Monitoring Errors , Faults , and Failures

Monitoring

errors, faults, and failures is very useful for:

• evaluating

product quality;

• evaluating

testing effectiveness; making stop-test decisions;

defect

casual analysis;

• defect

prevention;

• test

process improvement;

• development

process improvement.

Test

logs, test incident reports, and problem reports provide test managers with

some of the raw data for this type of tracking. Test managers usually want to

track defects discovered as the testing process continues over time to address

the second and third items above. The other items are useful to SQA staff,

process engineers, and project managers. At higher levels of the TMM where

defect data has been carefully stored and classified, mangers can use past defect

records from similar projects or past releases to compare the current project

defect discovery rate with those of the past. This is useful information for a

stop-test decision (see Section 9.3). To strengthen the value of defect/failure

information, defects should be classified by type, and severity levels should

be established depending on the impact of the defect/failure on the user. If a

failure makes a system inoperable it has a higher level of severity than one

that is just annoying. A example of a severity level rating hierarchy is shown

in Figure 9.3.

Some

useful measures for defect tracking are:

Total number of incident reports (for a

unit, subsystem, system)*

Number of incident reports resolved/unresolved (for

all levels of test)* Number of

defects found of each given type*

Number of defects causing failures of severity

level greater than X found (where X is an appropriate integer value)

Number of defects/KLOC (This is called the defect

volume. The division by KLOC normalizes the defect count)*

Number of failures*

Number of failures over severity level Y (where Y

is an appropriate integer value) Number of defects repaired*

Estimated number of defects (from historical data)

Other

failure-related data that are useful for tracking product reliability will be

discussed in later chapters.

Monitoring Test Effectiveness

To

complete the discussion of test controlling and monitoring and the role of test

measurements we need to address what is called test effectiveness. Test

effectiveness measurements will allow managers to determine if test resources

have been used wisely and productively to remove defects and evaluate product

quality. Test effectiveness evaluations allow managers to learn which testing

activities are or are not productive. For those areas that need improvement,

responsible staff should be assigned to implement and monitor the changes. At

higher levels of the TMM members of a process improvement group can play this

role. The goal is to make process changes that result in improvements to the

weak areas. There are several different views of test effectiveness. One of

these views is based on use of the number of defects detected. For example, we

can say that our testing process was effective if we have successfully revealed

all defects that have a major impact on the users. We can make such an

evaluation in several ways, both before and after release.

1. Before release. Compare the numbers of

defects found in testing for this software product to the number expected from

historical data. The ratio is:

Number of defects found during test/number of

defects estimated

This will

give some measure of how well we have done in testing the current software as

compared to previous similar products. Did we find more or fewer errors given

the test resources and time period? This is not the best measure of

effectiveness since we can never be sure that the current release contains the

same types and distribution of defects as the historical example.

2. After release. Continue to collect

defect data after the software has been released in the field. In this case the

users will prepare problem reports that can be monitored. Marks suggests we use

measures such as ―field fault density‖ as a

measure of test effectiveness. This is equal to:

Number of defects found/thousand lines of new and

changed code. This measure is applied to new releases of the

software. Another measure suggested

is a ratio of:

Pre-ship fault density/Post-ship fault density .

This

ratio, sometimes called the ―defect removal efficiency,‖ gives an indication of how many

defects remain in the software when it is released. As the testing process

becomes more effective, the number of predelivery defects found should increase

and postdelivery defects found should fall. The value of the postship fault

density (number of faults/KLOC) is calculated from the problem reports returned

to the development organization, so testers need to wait until after shipment

to calculate this ratio. Testers must examine the problem reports in detail

when using the data.

There may

be duplicate reports especially if the software is released to several

customers. Some problem reports are due to misunderstandings; others may be

requests for changes not covered in the requirements. All of these should be

eliminated from the count. Other measurements for test effectiveness have been

proposed. For example,:

Number of defects detected in a given test

phase/total number of defects found in testing.

For

example, if unit test revealed 35 defects and the entire testing effort

revealed 100 defects, then it could be said that unit testing was 35%

effective. If this same software was sent out to the customer and 25 additional

defects were detected, then the effectiveness of unit test would then be

25/125, or 20%. Testers can also use this measure to evaluate test

effectiveness in terms of the severity of the failures caused by the defects.

In the unit test example, perhaps it was only 20% effective in finding defects

that caused severe failures. The fault seeding technique as described in

Section 9.3 could also be applied to evaluate test effectiveness. If you know

the number of seeded faults injected and the number of seeded faults you have

already found, you can use the ratio to estimate how effective you have been in

using your test resources to date. Another useful measure, called the ―detect

removal leverage (DRL)‖

described in Chapter 10 as a review measurement, can be applied to measure the

relative effectiveness of: reviews versus test phases, and test phases with

respect to one another. The DRL sets up ratios of defects found. The ratio

denominator is the base line for comparison. For example, one can compare:

DRL

(integration/unit test) _ Number of defects found integration test Number of

defects found in unit test

Section

10.7 gives more details on the application of this metric. The costs of each

testing phase relative to its defect detecting ability can be expressed as:

Number of

defects detected in testing phase X Costs of testing in testing phase X

Instead

of actual dollar amounts, tester hours, or any other indicator of test resource

units could also be used in the denominator. These ratios could calculated for

all test phases to compare their relative effectiveness. Comparisons could lead

to test process changes and improvements. An additional approach to measuring

testing effectiveness is described by Chernak [8]. The main objectives of

Chernak‘s research are (i) to show how to determine if a set of test cases (a

test suite) is sufficiently effective in revealing defects, and (ii) to show

how effectiveness measures can lead to process changes and improvements. The

effectiveness metric called the TCE is defined as follows:

Number of

defects found by the test cases TCE _Total number of defects _ 100

The total

number of defects in this equation is the sum of the defects found by the test

cases, plus the defects found by what Chernak calls side effects. Side effect

are based on so-called ―testescapes.‖ These

are software defects that a test suite does not detect but are found by chance

in the testing cycle.

Test

escapes occur because of deficiencies in the testing process. They are

identified when testers find defects by executing some steps or conditions that

are not described in a test case specification. This happens by accident or

because the tester gets a new idea while performing the assigned testing tasks.

Under these conditions a tester may find additional defects which are the

test-escapes. These need to be recorded, and a casual analysis needs to be done

to develop corrective actions. The use of Chernak‘s metric depends on finding

and recording these types of defects. Not all types of projects are candidates

for this type of analysis. From his experience, Chernak suggests that

client-server business applications may be appropriate projects. He also

suggests that a baseline value be selected for the TCE and be assigned for each

project.

When the

TCE value is at or above the baseline then the conclusion is that the test

cases have been effective for this test cycle, and the testers can have some

confidence that the product will satisfy the uses needs. All test case escapes,

especially in the case of a TCE below the specified baseline, should be studied

using Pareto analysis and Fishbone diagram techniques (described in Chapter

13), so that test design can be improved, and test process deficiencies be

removed. Chernak illustrates his method with a case study (a client-server

application) using the baseline TCE to evaluate test effectiveness and make

test process improvements. When the TCE in the study was found to be below the

baseline value (_ 75 for this case), the organization analyzed all the

test-escapes, classified them by cause, and built a Pareto diagram to describe

the distribution of causes.

Incomplete

test design and incomplete functional specifications were found to be the main

causes of test-escapes. The test group then addressed these process issues,

adding both reviews to their process and sets of more ―negative‖ test cases to improve the

defect-detecting ability of their test suites.The TMM level number determined

for an organization is also a metric that can be used to monitor the testing

process. It can be viewed as a high-level measure of test process

effectiveness, proficiency, and overall maturity. A mature, testing process is

one that is effective. The TMM level number that results from a TMM assessment

is a measurement that gives an organization information about the state of its

testing process. A lower score on theTMMlevel number scale indicates a less

mature, less proficient, less effective testing process state then a

higher-level score. The usefulness of the TMM level number as a measurement of

testing process strength, proficiency, and effectiveness is derived not only

from its relative value on the TMM maturity scale, but also from the process

profile that accompanies the level number showing strong and weak testing

areas. In addition, the maturity goals hierarchy give structure and direction

to improvement efforts so that the test process can become more effective.

Related Topics