Chapter: Software Testing : Controlling and Monitoring

Components of review plans

Components of review plans

Reviews

are development and maintenance activities that require time and resources.

They should be planned so that there is a place for them in the project

schedule. An organization should develop a review plan template that can be applied

to all software projects. The template should specify the following items for

inclusion in the review plan.

• review

goals;

• items

being reviewed;

• preconditions

for the review;

• roles,

team size, participants;

• training

requirements;

• review

steps;

checklists

and other related documents to be disturbed to participants;

• time

requirements;

• the

nature of the review log and summary report;

• rework

and follow-up.

We will

now explore each of these items in more detail.

Review Goals

As in the

test plan or any other type of plan, the review planner should specify the

goals to be accomplished by the review. Some general review goals have been

stated in Section 9.0 and include (i) identification of problem components or

components in the software artifact that need improvement, (ii) identification

of specific errors or defects in the software artifact, (iii) ensuring that the

artifact conforms to organizational standards, and (iv) communication to the

staff about the nature of the product being developed. Additional goals might

be to establish traceability with other project documents, and familiarization

with the item being reviewed. Goals for inspections and walkthroughs are

usually different; those of walkthroughs are more limited in scope and are

usually confined to identification of defects.

Pre conditions and Items to Be Reviewed

Given the

principal goals of a technical review—early defect detection, identification of

problem areas, and familiarization with software artifacts— many software items

are candidates for review. In many organizations the items selected for review

include:

• requirements

documents;

• design

documents;

• code;

• test

plans (for the multiple levels);

• user

manuals;training manuals;

• standards

documents.

Note that

many of these items represent a deliverable of a major life cycle phase. In

fact, many represent project milestones and the review serves as a progress

marker for project progress. Before each of these items are reviewed certain

preconditions usually have to be met. For example, before a code review is

held, the code may have to undergo a successful compile. The preconditions need

to be described in the review policy statement and specified in the review plan

for an item. General preconditions for a review are:

(i)

the review of an item(s) is a required activity in

the project plan. (Unplanned reviews are also possible at the request of

management, SQA or software engineers. Review policy statements should include

the conditions for holding an unplanned review.)

(ii) a

statement of objectives for the review has been developed;

(iii)

the individuals responsible for developing the

reviewed item indicate readiness for the review;

(iv) the review leader believes that

the item to be reviewed is sufficiently complete for the review to be useful [8].

The

review planner must also keep in mind that a given item to be reviewed may be

too large and complex for a single review meeting. The smart planner partitions

the review item into components that are of a size and complexity that allows

them to be reviewed in 1-2 hours. This is the time range in which most

reviewers have maximum effectiveness. For example, the design document for a

procedure-oriented system may be reviewed in parts that encompass:

(i) the

overall architectural design;

(ii)

data items and module interface design;

(iii)component

design.

If the

architectural design is complex and/or the number of components is large, then

multiple design review sessions should be scheduled for each. The project plan

should have time allocated for this.

Roles , Participants , Team Size , and Time

Requirements

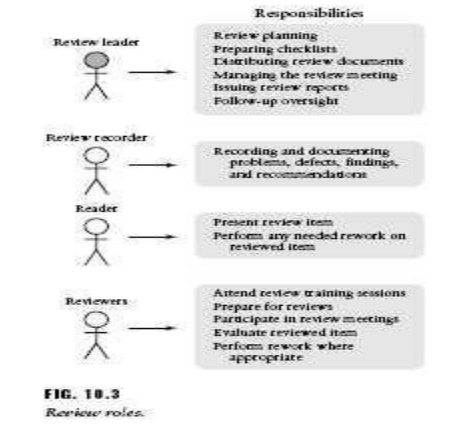

Two major

roles that need filling for a successful review are (i) a leader or moderator,

and (ii) a recorder. These are shown in Figure 10.3. Some of the

responsibilities of the moderator have been described. These include planning

the reviews, managing the review meeting, and issuing the review report.

Because of these responsibilities the moderator plays an important role; the

success of the review depends on the experience and expertise of the moderator.

Reviewing a software item is a tedious process and requires great attention to

details. The moderator needs to be sure that all are prepared for the review

and that the review meeting stays on track. Reviewers often tire and become

less effective at detecting errors if the review time period is too long and

the item is too complex for a single review meeting. The moderator/planner must

ensure that a time period is selected that is appropriate for the size and

complexity of the item under review. There is no set value for a review time

period, but a rule of thumb advises that a review session should not be longer

than 2 hours [3]. Review sessions can be scheduled over 2-hour time periods

separated by breaks. The time allocated for a review should be adequate enough

to ensure that the material under review can be adequately covered.

The

review recorder has the responsibility for documenting defects, and recording

review findings and recommendations, Other roles may include a reader who reads

or presents the item under review. Readers are usually the authors or preparers

of the item under review. The author(

s) is

responsible for per forming any rework on the reviewed item. In a walkthrough

type of review, the author may serve as the moderator, but this is not true for

an inspection. All reviewers should be trained in the review process. The size

of the review team will vary depending type, size, and complexity of the item

under review. Again, as with time, there is no fixed size for a review team. In

most cases a size between 3 and 7 is a rule of thumb, but that depends on the

items under review and the experience level of the review team. Of special

importance is the experience of the review moderator who is responsible for

ensuring the material is covered, the review meeting stays on track, and review

outputs are produced. The minimal team size of 3 ensures that the review will

be public [6].

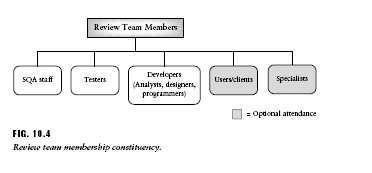

Organizational

policies guide selection of review team members. Membership may vary with the

type of review. As shown in Figure 10.4 the review team can consist of software

quality assurance staff members, testers, and developers (analysts, designers,

programmers). In some cases the size of the review team will be increased to

include a specialist in a particular area related to the reviewed item; in

other cases ―outsiders‖ may be

invited to a review to get a more unbiased evaluation of the item. These

outside members may include users/clients. Users/clients should certainly be

present at requirements, user manual, and acceptance test plan reviews. Some

recommend that users also be present at design and even code reviews.

Organizational policy should refer to this issue, keeping in mind the limited

technical knowledge of most users/clients.

In many

cases it is wise to invite review team members from groups that were involved

in the preceding and succeeding phases of the life cycle document being

reviewed. These participants could be considered to be outsiders. For example,

if a design document is under review, it would be useful to invite a

requirements team representative and a coding team member to be a review

participant since correctness, consistency, implementability, and traceability

are important issues for this review. In addition, these attendees can offer

insights and perspectives that differ from the group members that were involved

in preparing the current document under review. It is the author‘s option that

testers take part in all major milestone reviews to ensure:

• effective

test planning;

• traceability

between tests, requirements, design and code elements;

• discussion,

and support of testability issues;

• support

for software product quality issues;

• the

collection and storage of review defect data;

• support

for adequate testing of ―trouble-prone‖ areas.

Testers

need to especially interact with designers on the issue of testability. A more

testable design is the goal. For example, in an object-oriented system a tester

may request during a design review that additional methods be included in a

class to display its state variables. In this case and others, it may appear on

the surface that this type of design is more expensive to develop and

implement. However, consider that in the long run if the software is more

testable there will be two major positive effects:

(i) the

testing effort is likely to be decreased, thus lowering expenses, and

(ii) the

software is likely to be of higher quality, thus increasing customer

satisfaction.

Review Procedures

For each

type of review that an organization wishes to implement, there should be a set

of standardized steps that define the given review procedure. For example, the

steps for an inspection are shown in Figure 10.2. These are initiation,

preparation, inspection meeting, reporting results, and rework and follow-up.

For each step in the procedure the activities and tasks for all the reviewer

participants should be defined. The review plan should refer to the

standardized procedures where applicable.

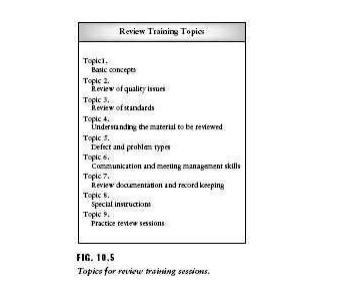

Review Training

Review

participants need training to be effective. Responsibility for reviewer

training classes usually belongs to the internal technical training staff.

Alternatively, an organization may decide to send its review trainees to

external training courses run by commercial institutions. Review participants,

and especially those who will be review leaders, need the training. Test

specialists should also receive review training. Suggested topics for a

training program are shown in Figure 10.5 and described below. Some of the

topics can be covered very briefly since it is assumed that the reviewers

(expect for possible users/clients) are all technically proficient.

1 . Review of Process Concepts.

Reviewers

should understand basic process concepts, the value of process improvement, and

the role of reviews as a product and process improvement tool.

2 . Review of Quality Issues.

Reviewers

should be made familiar with quality attributes such as correctness,

testability, maintainability, usability, security, portability, and so on, and

how can these be evaluated in a review.

3 . Review of Organizational Standards for Software

Artifacts .

Reviewers

should be familiar with organizational standards for software artifacts. For

example, what items must be included in a software document; what is the

correct order and degree of coverage of topics expected; what types of

notations are permitted. Good sources for this material are IEEE standards and

guides [1,9,10].

4 . Understanding the Material to Be Reviewed.

Concepts

of understanding and how to build mental models during comprehension of code

and software-related documents should be covered. A critical issue is how fast

a reviewed document should be read/checked by an individual and by the group as

a whole. This applies to requirements,design, test plans and other documents,

as well as source code. A rate of 5-10 pages/hour or 125-150 LOC/hour for a

review group has been quoted as favorable [7]. Reading rates that are too slow

will make review meetings ineffective with respect to the number of defects

found per unit time. Readings that are too fast will allow defects and problems

to go undetected.

5 . Defect and Problem Types.

Review

trainees need to become aware of the most frequently occurring types of

problems or errors that are likely to occur during development. They need to be

aware what their causes are, how they are transformed into defects, and where

they are likely to show up in the individual deliverables. The trainees should

become familiar with the defect type categories, severity levels, and numbers

and types of defects found in past deliverables of similar systems. Review

trainees should also be made aware of certain indicators or clues that a

certain type of defect or problem has occurred [3]. The definitions of defects

categories, and maintenance of a defect data base are the responsibilities of

the testers and SQA staff.

6 . Communication and Meeting Management Skills .

These

topics are especially important for review leaders. It is their responsibility

to communicate with the review team, the preparers of the reviewed document,

management, and in some cases clients/user group members. Review leaders need

to have strong oral and written communication skills and also learn how to

conduct a review meeting. During a review meeting there are interactions and

expression of opinion from a group of technically qualified people who often

want to be heard. The review leader must ensure that all are prepared, that the

meeting stays on track, that all get a chance to express their opinions, that

the proper page/code document checking rate is achieved, and that results are

recorded. Review leaders also must trained so that they can ensure that authors

of the document or artifact being reviewed are not under the impression that

they themselves are being evaluated. The review leader needs to uphold the

organizational view that the purpose of the review is to support the authors in

improving the quality of the item they have developed. Policy statements to

this effect need to be written and explained to review trainees, especially

those who will be review leaders.

Skills in

conflict resolution are very useful, since very often reviewers will have

strong opinions and arguments can dominate a review session unless there is intervention

by the leader. There are also issues of power and control over deliverables and

aspects of deliverables and other hidden agenda that surface during a review

meeting that must be handled by the review leader. In this case people and

management skills are necessary, and sometime these cannot be taught. They come

through experience.

7 . Review Documentation and Record Keeping.

Review

leaders need to learn how to prepare checklists, agendas, and logs for review

meetings. Examples will be provided for some of these documents later in this

chapter. Other examples can be found in Freedman and Weinberg [6], Myers [11],

and Kit [12]. Checklists for inspections should be appropriate for the item

being inspected. Checklists in general should focus on the following issues:

• most

frequent errors;

• completeness

of the document;

• correctness

of the document;

• adherence

to standards.

8 . Special Instructions.

During

review training there may be some topics that need to be covered with the

review participants. For example, there may be interfaces with hardware that

involve the reviewed item, and reviewers may need some additional background

discussion to be able to evaluate those interfaces.

9 . Practice Review Sessions.

Review

trainees should participate in practice review sessions. There are very

instructive and essential. One option is for instructors to use existing

documents that have been reviewed in the past and have the trainees do a

practice review of these documents. Results can be compared to those of experienced

reviewers, and useful lessons can be learned from problems identified by the

trainees and those that were not. Instructors can discuss so-called ―false

positives‖ which

are not true defects but are identified as such. Trainees can also attend review

sessions with experienced reviewers as observers, to learn review lessons.

In

general, training material for review trainees should have adequate examples,

graphics, and homework exercises. Instructors should be provided with the media

equipment needed to properly carry out instruction. Material can be of the

self-paced type, or for group course work.

Review Checklists

Inspections

formally require the use of a checklist of items that serves as the focal point

for review examinations and discussions on both the individual and group

levels. As a precondition for checklist development an organization should

identify the typical types of defects made in past projects, develop a

classification scheme for those defects, and decide on impact or severity categories

for the defects. If no such defect data is available, staff members need to

search the literature, industrial reports, or the organizational archives to

retrieve this type of information.

Checklists

are very important for inspectors. They provide structure and an agenda for the

review meeting. They guide the review activities, identify focus areas for

discussion and evaluation, ensure all relevant items are covered, and help to

frame review record keeping and measurement. Reviews are really a two-step

process: (i) reviews by individuals, and (ii) reviews by the group. The

checklist plays its important role in both steps. The first step involves the

individual reviewer and the review material. Prior to the review meeting each

individual must be provided with the materials to review and the checklist of

items. It is his responsibility to do his homework and individually inspect

that document using the checklist as a guide, and to document any problems he

encounters.

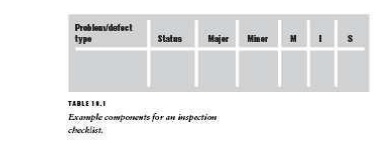

When they

attend the group meeting which is the second review step, each reviewer should

bring his or her individual list of defect/problems, and as each item on the

checklist is discussed they should comment. Finally, the reviewers need to come

to a consensus on what needs to be fixed and what remains unchanged. Each item

that undergoes a review requires a different checklist that addresses the

special issues associated with quality evaluation for that item. However each

checklist should have components similar to those shown in Table 10.1. The

first column lists all the defect types or potential problem areas that may

occur in the item under review. Sources for these defect types are usually data

from past projects. Abbreviations for detect/ problem types can be developed to

simplify the checklist forms. Status refers to coverage during the review

meeting —has the item been discussed? If so, a check mark is placed in the

column. Major or minor are the two severity or impact levels shown here. Each

organization needs to decide on the severity levels that work for them. Using

this simple severity scale, a defect or problem that is classified as major has

a large impact on product quality; it can cause failure or deviation from

specification. A minor problem has a small impact on these; in general, it

would affect a nonfunctional aspect of the software. The letters M, I, and S

indicate whether a checklist item is missing (M), incorrect (I), or superfluous

(S).

In this

section we will look at several sample checklists. These are shown in Tables

10.2-10.5. One example is the general checklist shown in Table 10.2, which is

applicable to almost all software documents. The checklist is used is to ensure

that all documents are complete, correct, consistent, clear, and concise. Table

10.2 only shows the problem/defect types component

(column)

for simplicity‘s sake. All the components as found in Table 10.1 should be

present on each checklist form. That also holds true for the checklists

illustrated in Tables 10.3-10.5. The recorder is responsible for completing the

group copy of the checklist form during the review meeting (as opposed to the

individual checklist form completed during review preparation by each

individual reviewer). The recorder should also keep track of each defect and

where in the document it occurs (line, page, etc.). The group checklist can

appear on a wallboard so that all can see what has been entered. Each

individual should bring to the review meeting his or her own version of the

checklist completed prior to the review meeting.In addition to using the widely

applicable problem/defect types shown in Table 10.2 each item undergoing review

has

specific

attributes that should be addressed on a checklist form. Some examples will be

given in the following pages of checklist items appropriate for reviewing

different types of software artifacts.

Requirements Reviews

In

addition to covering the items on the general document checklist as shown in

Table 10.2, the following items should be included in the checklist for a

requirements review.

• completeness

(have all functional and quality requirements described in the problem

statement been included?);

• correctness

(do the requirements reflect the user‘s needs? are they stated without error?);

• consistency

(do any requirements contradict each other?);

• clarity

(it is very important to identify and clarify any ambiguous requirements);

• relevance

(is the requirement pertinent to the problem area? Requirements should not be

superfluous);

•

redundancy (a requirement may be repeated; if it is

a duplicate it should be combined with an equivalent one);

• testability

(can each requirement be covered successfully with one or more test cases? can

tests determine if the requirement has been satisfied?);feasibility (are

requirements implementable given the conditions underwhich the project will

progress?).

Users/clients

or their representatives should be present at a requirements review to ensure

that the requirements truly reflect their needs, and that the requirements are

expressed clearly and completely. It is also very important for testers to be

present at the requirements review. One of their major responsibilities it to

ensure that the requirements are testable. Very often the master or early

versions of the system and acceptance test plans are included in the

requirements review. Here the reviewers/testers can use a traceability matrix

to ensure that each requirement can be covered by one or more tests. If

requirements are not clear, proposing test cases can be of help in focusing

attention on these areas, quantifying imprecise requirements, and providing

general information to help resolve problems.

Although

not on the list above, requirements reviews should also ensure that the

requirements are free of design detail. Requirements focus on what the system

should do, not on how to implement it.

Design Reviews

Designs

are often reviewed in one or more stages. It is useful to review the high level

architectural design at first and later review the detailed design. At each

level of design it is important to check that the design is consistent with the

requirements and that it covers all the requirements. Again the general

checklist is applicable with respect to clarity, completeness, correctness and

so on. Some specific items that should be checked for at a design review are:

• a

description of the design technique used;

• an

explanation of the design notation used;

•

evaluation of design alternatives (it is important

to establish that design alternatives have been evaluated, and to determine why

this particular approach was selected);

• quality

of the high-level architectural model (all modules and their relationships

should be defined; this includes newly developed modules, revised modules, COTS

components, and any

other

reused modules; module coupling and cohesion should be evaluated.);

• description

of module interfaces;

• quality

of the user interface;

• quality

of the user help facilities;

• identification

of execution criteria and operational sequences;

• clear

description of interfaces between this system and other software and hardware

systems;

• coverage

of all functional requirements by design elements; coverage of al l quality

requirements, for example, ease of use, portability, maintainability, security,

readability, adaptability, performance requirements (storage, response time) by

design elements;

• reusability

of design components;

• testability

(how will the modules, and their interfaces be tested? How will they be

integrated and tested as a complete system?).

For

reviewing detailed design the following focus areas should also be revisited:

• encapsulation,

information hiding and inheritance;

• module

cohesion and coupling;

• quality

of module interface description;

• module

reuse.

Both

levels of design reviews should cover testability issues as described above. In

addition, measures that are now available such as module complexity, which

gives an indication of testing effort, can be used to estimate the extent of

the testing effort. Reviewers should also check traceability from tests to

design elements and to requirements. Some organizations may re-examine system

and integration test plans in the context of the design elements under review.

Preliminary unit test plans can also be examined along with the design

documents to ensure traceability, consistency, and complete coverage. Other

issues to be discussed include language issues and the appropriateness of the

proposed language to implement the design.

Code Reviews

Code

reviews are useful tools for detecting defects and for evaluating code quality.

Some organizations require a clean compile as a precondition for a code review.

The argument is that it is more effective to use an automated tool to identify

syntax errors than to use human experts to perform this task. Other

organizations will argue that a clean compile makes rediligent in checking for

defects since they will assume the compiler has detected many of them.

Code

review checklists can have both general and language-specific components. The

general code review checklist can be used to review code written in any

programming language. There are common quality features that should be checked

no matter what implementation language is selected. Table 10.3 shows a list of

items that should be included in a general code checklist. The general

checklist is followed by a sample checklist that can be used for a code review

for programs written in the C programming language. The problem/defect types

are shown in Table

10.4.

When developing your own checklist documents be sure to include the other

columns as shown in Table 10.1. The reader should note that since the

languagespecific checklist addresses programming-language-specific issues, a

different checklist is required for each language used in the organization.

Test Plan Reviews

Test

plans are also items that can be reviewed. Some organizations will review them

along with other related documents. For example, a master test plan and an

acceptance test plan could be reviewed with the requirements document, the

integration and system test plans reviewed with the design documents, and unit

test plans reviewed with detailed design documents [2]. Other organizations,

for example, those that use the Extended/ Modified V-model, may have separate

review meetings for each of the test plans. In Chapter 7 the components of a

test plan were discussed, and the review should insure that all these

components are present and that they are correct, clear, and complete. The

general document checklist can be applied to test plans, and a more specific

checklist can be developed for test-specific issues. An example test plan

checklist is shown in Table 10.4. The test plan checklist is applicable to all

levels of test plans.

Other

testing products such as test design specifications, test procedures, and test

cases can also be reviewed. These reviews can be held in conjunction with

reviews of other test-related items or other software items.

Related Topics