Chapter: Obstetrics and Gynecology: Maternal-Fetal Physiology

Maternal Physiology: Cardiovascular System

MATERNAL PHYSIOLOGY

Cardiovascular System

The

earliest and most dramatic changes in maternal physiology are cardiovascular. These

changes improve fetal oxygena-tion and nutrition.

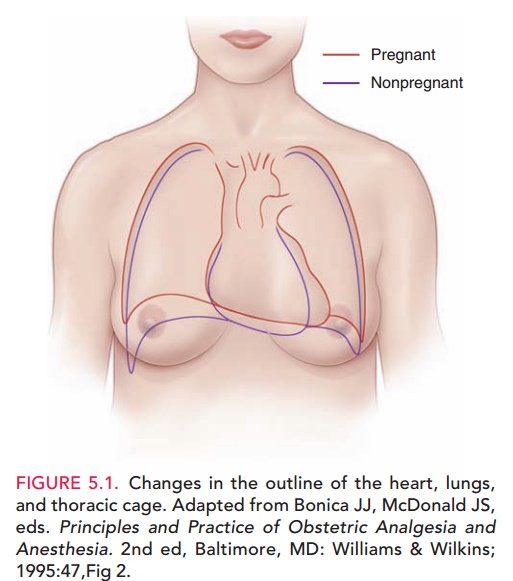

ANATOMIC CHANGES

During pregnancy, the heart is

displaced upward and to the left and assumes a more horizontal position as its

apex is moved laterally (Fig. 5.1). These position changes are the result of

diaphragmatic elevation caused by displace-ment of abdominal viscera by the

enlarging uterus. In addition, ventricular muscle mass increases and both the

left ventricle and atrium increase in size parallel with an increase in

circulating blood volume.

FUNCTIONAL CHANGES

The

primary functional change in the cardiovascular system in pregnancy is a marked

increase in cardiac output.

Overall, cardiac output increases

30% to 50%, with 50% of that increase occurring by 8 weeks’ gestation. In the

first half of pregnancy, cardiac output rises as a result of increased stroke

volume, and in the latter half of preg-nancy, as a result of increased maternal

heart rate while the stroke volume returns to near-normal, nonpregnant levels.

These changes in stroke volume are due to alter-ations in circulating blood

volume and systemic vascular resistance. Circulating blood volume begins

increasing by 6 to 8 weeks’ gestation and reaches a peak increase of 45% by 32

weeks’ gestation. Systemic vascular resistance decreases because of a

combination of the smooth muscle-relaxing effect of progesterone, increased

production of vasodilatory substances (prostaglandins, nitric oxide, atrial

natriuretic peptide), and arteriovenous shunting to the uteroplacental

circulation.

However, late in pregnancy,

cardiac output may decrease when venous return to the heart is impeded because

of vena caval obstruction by the enlarging gravid uterus. At times, in term

pregnancy, nearly complete occlu-sion of the inferior vena cava occurs,

especially in the supine position, with venous return from the lower

extremities shunted primarily through the dilated paravertebral collat-eral

circulation.

The distribution of the enhanced

cardiac output varies during pregnancy. The uterus receives about 2% of the

cardiac output in the first trimester, increasing to up to 20% at term, mainly

by means of a relative reduction of the fraction of cardiac output that goes to

the splanchnic bed and skeletal muscle. However, the absolute blood flow to

these areas does not change, because of the increase in cardiac output that

occurs in late pregnancy.

During pregnancy, arterial blood

pressure follows a typical pattern. When measured in the sitting or stand-ing

position, diastolic blood pressure decreases begin-ning in the 7th week of

gestation and reaches a maximal decline of 10 mm Hg from 24 to 32 weeks. Blood

pres-sure then gradually returns to nonpregnant values by term. Resting

maternal pulse increases as pregnancy pro-gresses, increasing by 10–18 beats

per minute over the nonpregnant value by term.

During labor, at the time of

uterine contraction, car-diac output increases approximately 40% above that in

late pregnancy, and mean arterial pressure increases by approx-imately 10 mm

Hg. A decline in these parameters follow-ing administration of an epidural

anesthetic suggests that many of these changes are the result of pain and

apprehen-sion. Cardiac output increases significantly immediately after

delivery, because venous return to the heart is no longer blocked by the gravid

uterus impinging on the vena cava and because extracellular fluid is quickly

mobilized.

SYMPTOMS

Although most women do not become

overtly hypoten-sive when lying supine, perhaps one in 10 have symptoms that

include dizziness, light-headedness,

and syncope. These symptoms, often

termed the inferior vena cava syn-drome, may be related to ineffective shunting

via the paravertebral circulation when the gravid uterus occludes the inferior

vena cava.

PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The cardiovascular system is in a

hyperdynamic state dur-ing pregnancy. Normal

physical findings on cardiovascularexamination include an increased second heart sound splitwith inspiration, distended neck

veins, and low-grade sys-tolic

ejection murmurs, which are presumably associated withincreased blood flow

across the aortic and pulmonic valves. Manynormal pregnant women have an S3

gallop, or third heart sound, after midpregnancy. Diastolic murmurs should not

be considered normal in pregnancy.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

Serial

blood pressure assessment is an essential component of each prenatal care

visit.

Blood pressure recordings during

pregnancy are influ-enced by maternal position; therefore, a consistent

position should be used during prenatal care, facilitating the recog-nition of

trends in blood pressure during pregnancy and their documentation. Measured blood pressure is highest whena

pregnant woman is seated, somewhat lower when supine, and lowest while lying on

the side. In the lateral recumbent posi-tion, the measured pressure in the

superior arm is about 10 mm Hg lower than that simultaneously measured in the

inferior arm. Blood pressures higher than the nonpregnant values for a

particular patient should be presumed abnor-mal pending evaluation.

The normal anatomic changes of

the maternal heart in pregnancy can produce subtle, but insignificant, changes

in chest radiographs and electrocardiograms. In chest radio-graphs, the cardiac

silhouette can appear enlarged, causing a misinterpretation of cardiomegaly. In

electrocardiograms, a slight left axis deviation may be apparent.

Related Topics