Chapter: Obstetrics and Gynecology: Ovarian and Adnexal Disease

Malignant Ovarian Neoplasms

MALIGNANT OVARIAN NEOPLASMS

Ovarian

cancer is the fifth most common of all cancers in women in the United States

and the most common cause of gynecologic cancer. The mortality rate of this

disease is the highest of all the gynecologic malignancies, primarily

because of the difficultyin detecting the disease before widespread

dissemination. Of the estimated 25,000 new cases of ovarian cancer yearly,

approximately 60% will die within 5 years. Sixty-five to seventy percent are

diagnosed at an advanced state when the 5-year survival rate is 20–30%.

Risk Factors and Early Symptoms

Ovarian

cancer presents most commonly in the fifth and sixth decades of life. The

incidence of ovarian cancer in WesternEuropean countries and in the United

States is higher, with a five- to sevenfold greater incidence than age-matched

populations in East Asia. Whites are 50% more likely to develop ovarian cancer

than blacks living in the United States.

Symptoms of ovarian cancer are often

confused with benign conditions or interpreted as part of the aging process,

with the final diagnosis often delayed.

The most

common symptoms in order from highest percent-age to lowest are abdominal

fullness or distension, abdomi-nal or back pain, decreased energy or lethargy,

and urinary frequency.

Because no clinically applicable

screening test is avail-able, approximately two-thirds of patients with ovarian

cancer have advanced disease at the time of diagnosis.

The risk

of a woman developing ovarian cancer during her lifetime is approximately 1 in

70. The risk increaseswith age until approximately age

70. In addition to age, the epidemiologic factors associated with development

of ovarian cancer include nulliparity, primary infertility, and endometriosis.

Approximately 8% to 13% of cases of ovarian cancer are caused by inherited

mutations in the cancer-susceptibility genes BRCA-1 and BRCA-2.

Addition-ally, women affected with hereditary nonpolyposis colo-rectal cancer

(HNPCC; formerly called Lynch syndrome) have approximately a 13-fold greater

risk of developing ovarian cancer than the general population.

Long-term

suppression of ovulation may protect against the development of ovarian cancer,

at least for epithelial celltumors. It has been

suggested that so-called incessant ovu-lation may predispose to neoplastic

transformation of the epithelial cell surfaces of the ovary. Oral

contraceptives that prevent ovulation appear to provide significant protec-tion

against the occurrence of ovarian cancer. Five years’ cumulative use of oral

contraceptives decreases the lifetime risk by one-half. No evidence exists to

implicate the use of postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy in the

development of ovarian cancer.

Pathogenesis and Diagnosis

Malignant

ovarian epithelial cell tumors spread primarily by direct extension within the

peritoneal cavity as a result of direct cell sloughing from the ovarian

surface. This processexplains widespread peritoneal

dissemination at the time of diagnosis, even with relatively small primary

ovarian lesions. Although epithelial cell ovarian cancers also spread by

lymphatic and blood-borne routes, their direct extension into the virtually

unlimited space of the peri-toneal cavity is the primary basis for their late

clinical presentation.

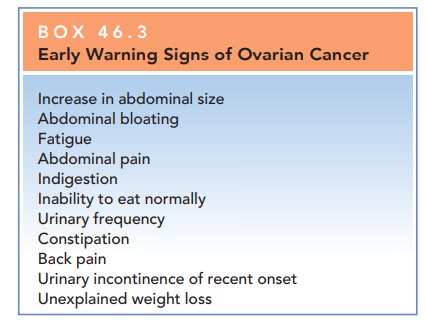

Currently, it appears that the

best way to detect early ovarian cancer is for both the patient and her

clinician to be aware of early warning signs (Box 46.3). These signs should not

be ignored in postmenopausal women (median age, approximately 60 years).

Early Warning Signs of Ovarian Cancer

Increase in abdominal size

Abdominal bloating

Fatigue

Abdominal pain

Indigestion

Inability to eat normally

Urinary frequency

Constipation

Back pain

Urinary incontinence of recent onset

Unexplained weight loss

The early diagnosis of ovarian cancer is made even more difficult by the lack of effective screening tests. CA-125 shouldnot be routinely used to screen for ovarian cancer, but, instead, should be used to follow response to therapy and evaluate for recurrent disease. CA-125 can also be used to evaluate the presence of ovarian cancer in selected cases:

·

In premenopausal women with

symptoms, a CA-125 measurement has not been shown to be useful in most

circumstances, because elevated levels of CA-125 are associated with a variety

of common benign conditions, including uterine leiomyomata, pelvic inflammatory

disease, endometriosis, adenomyosis, pregnancy, and even menstruation.

·

In postmenopausal women with a

pelvic mass, a CA-125 measurement may be helpful in predicting a higher

likelihood of a malignant tumor than a benign tumor. However, a normal CA-125

measurement alone does not rule out ovarian cancer, because up to 50% of

early-stage cancers and 20% to 25% of advanced cancers are associated with

normal values.

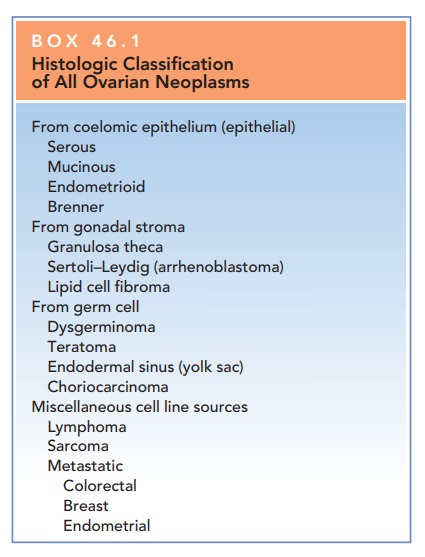

HISTOLOGIC CLASSIFICATION

The cell

type of origin, similar to their benign counterparts, usu-ally categorizes

malignant ovarian neoplasms: malignantepithelial

cell tumors, which are the most common type;malignant germ cell tumors; and malignant stromal celltumors (see Box 46.1). Most

malignant ovarian tumorshave histologically similar but benign counterparts.

The relationship between a benign ovarian neoplasm and its malignant

counterpart is clinically important. If the benign counterpart is found in a

patient, removal of both ovaries is considered, because there is a possibility

of future malig-nant transformation in the remaining ovary. The decision

regarding removal of one or both ovaries, however, must be individualized based

on age, type of tumor, desire for future fertility, genetic predisposition for

malignancy, and the patient’s concern regarding future risks.

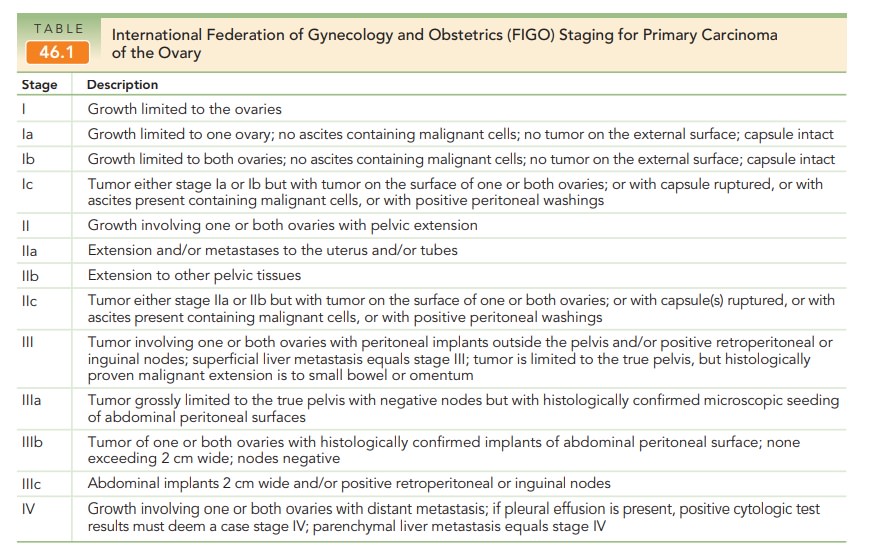

STAGING

The staging of ovarian carcinoma

is based on extent of spread of tumor and histologic evaluation of the tumor.

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obste-trics (FIGO)

classification of ovarian cancer is presented in Table 46.1.

Borderline Ovarian Tumors

Approximately

10% of seemingly benign epithelial cell tumors may contain histologic evidence

of intraepithelial neoplasia, com-monly referred to as borderline malignancies,

or “tumors of low malignant potential.” These

tumors generally remain con-fined to the ovary, are more common in

premenopausal women (30 to 50 years of age), and have good prognoses. About 20%

of such tumors show spread beyond the ovary. They require carefully

individualized therapy following the initial surgical resection of the primary

tumor. If frozen section pathology demonstrates borderline histology,

uni-lateral oophorectomy with a staging procedure and follow-up is appropriate,

assuming the woman wishes to retain ovarian function and/or fertility and

understands the risks of such conservative management.

Epithelial Cell Ovarian Carcinoma

Approximately

90% of all ovarian malignancies are of the epithelial cell type, derived from

mesothelial cells. The ovarycontains these cells as

part of an ovarian capsule just over-lying the actual stroma of the ovary. When

these meso-thelial cell elements are situated over developing follicles, they

go through metaplastic transformation whenever ovulation occurs. Repeated

ovulation is, therefore, associ-ated with the histologic change in these cells

derived from coelomic epithelium.

Malignant

epithelial serous tumors (serous cyst-adenocarcinoma) are

the most common malignant epithe-lial cell tumors. Approximately 50% of these

cancers are thought to be derived from their benign precursors (serous

cystadenoma), and as many as 30% of these tumors are bilateral at the time of

clinical presentation. They are typi-cally multiloculated and often have

external excrescences on an otherwise smooth capsular surface. Calcified,

laminated structures, psammoma bodies,

are found in more than one-half of serous carcinomas.

Another epithelial cell variant

that contains cells rem-iniscent of endocervical glandular mucous-secreting

cells is the malignant mucinous

epithelial tumor (mucinouscystadenocarcinoma). They make up

approximatelyone-third of all epithelial tumors, the majority of which are

benign or of low malignant potential; only 5% are can-cerous. These tumors have

a lower rate of bilaterality and can be among the largest of ovarian tumors,

often measur-ing more than 20 cm. They may be associated with wide-spread

peritoneal extension with thick, mucinous ascites, termed pseudomyxomatous peritonei.

Although most epithelial

carcinomas occur sporadi-cally, a small percentage (5% to 10%) occurs in

familial or hereditary patterns involving first- or second-degree

Having a first-degree relative (i.e., mother,

sister, daughter) with an epithelial carcinoma gives a 5% lifetime risk for

ovarian cancer, whereas having two first-degree relatives increases this risk

to 20% to 30%. Such hereditary ovarian cancers generally occur earlier than

nonhereditary tumors.

Women with breast/ovarian familial cancer syn-drome, a combination of

epithelial ovarian and breast can-cers in first- and second-degree family members,

are at two to three times the risk of these cancers as the general pop-ulation.

Women with this syndrome have an increased risk of bilaterality of breast

cancer and developing ovarian tumors at a younger age. This syndrome has been

associ-ated with the BRCA-1 gene.

Women with this gene muta-tion have a cumulative lifetime risk of 85% to 90%

for breast cancer and 50% for ovarian cancer. Women of Ashkenazi Jewish

ancestry have a 1% chance of carrying this gene, a 10-fold risk over the

general population.

HNPCC occurs in

families with first- and second-degree members with combinations of colon,

ovarian, endometrial, and breast cancers. Women in families with this syndrome

may have a threefold increased risk of cancer over the general population.

Women in families with these syndromes should have more frequent screening

tests and may benefit from risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy.

ENDOMETRIOID TUMORS

Most endometrioid tumors are malignant. These tumors contain histologic

features similar to those of endometrial carcinoma, and are commonly found in

association with endometriosis or are coincident with endometrial cancer of the

uterus.

OTHER EPITHELIAL CELL OVARIAN CARCINOMAS

Of the remaining epithelial cell

carcinomas of the ovary, clear cell carcinomas are thought to arise from

mesonephric elements, and Brenner tumors are thought to arise rarely from their

benign counterpart. Brenner tumors may occur in the same ovary that contains

mucinous cystadenoma; the reason for this is unclear.

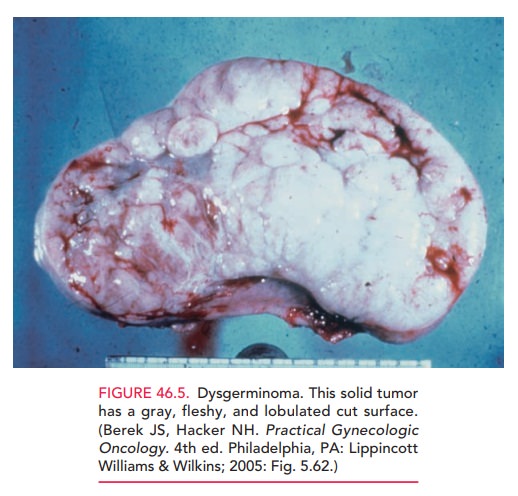

Germ Cell Tumors

Germ cell tumors are the most common ovarian

cancers inwomen younger than 20 years of age. Germ cell

tumors may befunctional, producing hCG or α-fetoprotein (AFP), both of which

can be used as tumor markers. The most common germ cell malignancies are dysgerminoma

and immatureteratoma. Other tumors are recognized as mixed germ cell tumors,

endodermal sinus tumors, and embryonal tumors. Improved chemotherapeutic and

radiation protocols have resulted in greatly improved 5-year survival rates.

Dysgerminomas are usually unilateral and are

the mostcommon type of germ cell tumor seen in patients with gonadal dysgenesis

(Fig. 46.5). These tumors often arise in

benigncounterparts, called the gonadoblastoma. The tumors are particularly

radiosensitive and chemosensitive.

Because of the young age of

patients with dysgermino-mas, removing only the involved ovary while preserving

the uterus and contralateral tube and ovary may be considered if the tumor is

less than approximately 10 cm and if no evi-dence of extraovarian spread is

found. Unlike the epithelial cell tumors, these malignancies are more likely to

spread by lymphatic channels, and therefore the pelvic and periaortic lymph

nodes must be sampled at the time of surgery. If dis-ease has spread outside

the ovaries, conventional hysterec-tomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy are

necessary, usually followed by cisplatin-based chemotherapy that is used in

combination with bleomycin and etoposide. The prognosis of these tumors is

generally excellent. The over-all 5-year survival rate for patients with

dysgerminoma is 90% to 95% when the disease is limited to one ovary.

Immature teratomas are the malignant counterpart ofbenign cystic teratomas (dermoids). These tumors are the sec-ond most common germ cell cancer and are most often found in women younger than 25 years of age. They are usually uni-lateral, although on occasion a benign counterpart may be found in the contralateral ovary. Because these tumors are rapidly growing, they may produce painful symptomatology relatively early, due to hemorrhage and necrosis. The dis-ease is therefore diagnosed when it is limited to one ovary in two-thirds of patients. As with dysgerminoma, if an imma-ture teratoma is limited to one ovary, unilateral oophorec-tomy is sufficient. Treatment with chemotherapeutic agents provides a good prognosis.

Rare Germ Cell Tumors

Endodermal

sinus tumors and

embryonal cell carcino-mas are uncommon malignant ovarian tumors that havehad

a remarkable improvement in cure rate. Until about 10 years ago, these tumors

were almost uniformly fatal. New chemotherapeutic protocols have resulted in an

over-all 5-year survival rate of more than 60%. These tumors typically occur in

childhood and adolescence, with the pri-mary treatment being surgical resection

of the involved ovary followed by combination chemotherapy. The endo-dermal

sinus tumor produces AFP, whereas the embryonal cell carcinoma produces both

AFP and β-hCG.

Gonadal Stromal Cell Tumors

The gonadal stromal cell tumors

make up an unusual group of tumors characterized by hormone production; hence,

these tumors are called functioning

tumors. The hormonal output from these tumors is usually in the form of

female or male sex steroids, or on occasion, adrenal steroid hormones.

The granulosa cell tumor is the most common in this group. These tumors

occur in all ages, although in older patients they are more likely to be

benign. Granulosa celltumors may secrete

large amounts of estrogen, which in some older women may cause endometrial

hyperplasia or endometrial carci-noma. Thus, endometrial sampling is

especially importantwhen ovarian tumors such as the granulosa tumor are

estrogen-producing. Surgical treatment should include removal of the uterus and

both ovaries in postmenopausal women as well as in women of reproductive age

who no longer wish to remain fertile. In a young woman with the lesion limited

to one ovary with an intact capsule, unilat-eral oophorectomy with careful

surgical staging may be adequate. This tumor may demonstrate recurrences up to

10 years later. This is especially true with large tumors, which have a 20% to

30% chance of late recurrence.

Sertoli–Leydig

cell tumors (arrhenoblastoma) are the rare, testosterone-secreting counterparts

to granulosa cell tumors. They usually occur in older

patients and should be sus-pected in the differential diagnosis of

perimenopausal or postmenopausal patients with hirsutism or virilization and an

adnexal mass. Treatment of these tumors is similar to that for other ovarian

malignancies in this age group, and is based on extirpation of uterus and

ovaries.

Other stromal cell tumors include

fibromas and thecomas, which rarely demonstrate malignant potential,and their

malignant counterparts, the fibrosarcoma

and malignant thecoma.

Other Ovarian Cancers

Rarely, the ovary may be the site

of initial manifestation of lymphoma. These tumors are usually found in

associ-ation with lymphoma elsewhere, although cases have been reported of

primary ovarian lymphoma. Once diag-nosed, their management is similar to that

for lymphoma of other origin.

Malignant

mesodermal sarcomas (carcinosarcomas)are another rare

type of ovarian tumor that usually show aggressive behavior and are diagnosed

at late stages. The survival rate is poor, and clinical experience with these

tumors is limited.

Cancer Metastatic to the Ovary

Classically, the term Krukenberg tumor describes an ovarian

tumor that is metastatic from other sites such as the gastrointestinal tract and

breast. Between 5% and 10% of women thought to have a primary ovarian

malignancy ultimately will receive the diagnosis of a nongenital tract

malignancy. Most of these tumors are characterized as infiltrative, mucinous

carcinoma of predominantly signet-ring cell type and as bilateral and

associated with wide-spread metastatic disease. On occasion, these tumors are

associated with abnormal uterine bleeding or virilization, leading to the

supposition that some may produce estro-gens or androgens. Breast cancer

metastatic to the ovary is common, with autopsy data suggesting ovarian

metastasis in one quarter of cases.

In approximately 10% of patients

with cancer metasta-tic to the ovary, an extraovarian primary site cannot be

demonstrated. In this regard, it is important to consider ovarian preservation

versus prophylactic oophorectomy at the time of hysterectomy in patients who

have a strong family history (first-degree relatives) of epithelial ovarian

cancer, primary gastrointestinal tract cancer, or breast can-cer. In patients

previously treated for breast or gastrointesti-nal cancer, consideration should

be given to the incidental removal of the ovaries at the time of hysterectomy,

because these patients have a high predilection for development of ovarian cancer.

The prognosis for most patients with carci-noma metastatic to the ovary is

generally poor.

Related Topics