Chapter: Medical Microbiology: An Introduction to Infectious Diseases: Flagellates

Leishmania - Parasitology

Leishmania

PARASITOLOGY

Leishmania species are obligate intracellular parasites of mammals. Several strains caninfect humans; they are all morphologically similar, resulting in some confusion over their proper speciation. Definitive identification of these strains requires isoenzyme analy-sis, monoclonal antibodies, kinetoplast DNA buoyant densities, DNA hybridization, and DNA restriction endonuclease fragment analysis or chromosomal karyotyping using pulse-field electrophoresis. The many strains can be more simply placed in four major groups based on their serologic, biochemical, cultural, nosologic, and behavioral charac-teristics. For the sake of clarity, these groups will be discussed as individual species. Each, however, contains a variety of strains that have been accorded separate species or subspecies status by some authorities. The organisms can be propagated in hamsters and in a variety of commercially available liquid media.

DISEASE TRANSMISSION

It is estimated that over 20 million people worldwide suffer from leishmaniasis and 1 to 2 million additional individuals acquire the infection annually. Leishmania tropicain the Old World and L. mexicana in the New World produce a localized cutaneous lesion or ulcer, known popularly as oriental sore and chiclero ulcer; L. braziliensis is the cause of American mucocutaneous leishmaniasis (espundia); and L. donovani is the etiologic agent of kala azar, a disseminated visceral disease.

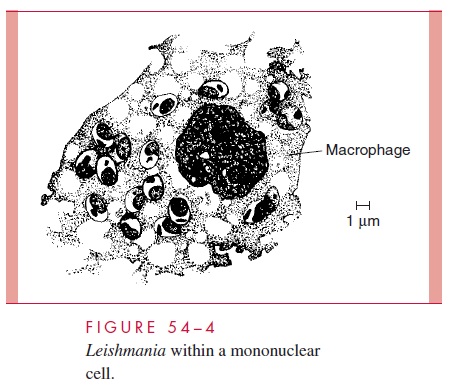

All four are transmitted by phlebotomine sandflies. These small, delicate, short-lived insects are found in animal burrows and crevices throughout the tropics and subtropics. At night, they feed on a wide range of mammalian hosts. Amastigotes ingested in the course of a meal assume the flagellated promastigote form, multiply within the gut, and eventually migrate to the buccal cavity. When the fly next feeds on a human or animal host, the buccal promastigotes are injected into the skin of the new host together with salivary peptides capable of inactivating host macrophages. Here, they activate comple-ment by the classic (L. donovani) or alternative pathway and are opsonized with C3, which mediates attachment to the CR1 and CR3 complement receptors of macrophages. Following phagocytosis, the promastigotes lose their flagella and multiply as the rounded amastigote form within the phagolysosome. In stained smears, the parasites take on a dis-tinctive appearance and have been termed Leishman – Donovan bodies. Intracellular sur-vival is mediated by a surface lipophosphoglycan and an abundance of membrane-bound acid phosphatase, which inhibit the macrophage’s oxidative burst and/or inactivate lyso-somal enzymes. Continued multiplication leads to the rupture of the phagocyte and re-lease of the daughter cells. Some may be taken up by a feeding sandfly; most invade neighboring mononuclear cells (Fig 54 – 4).

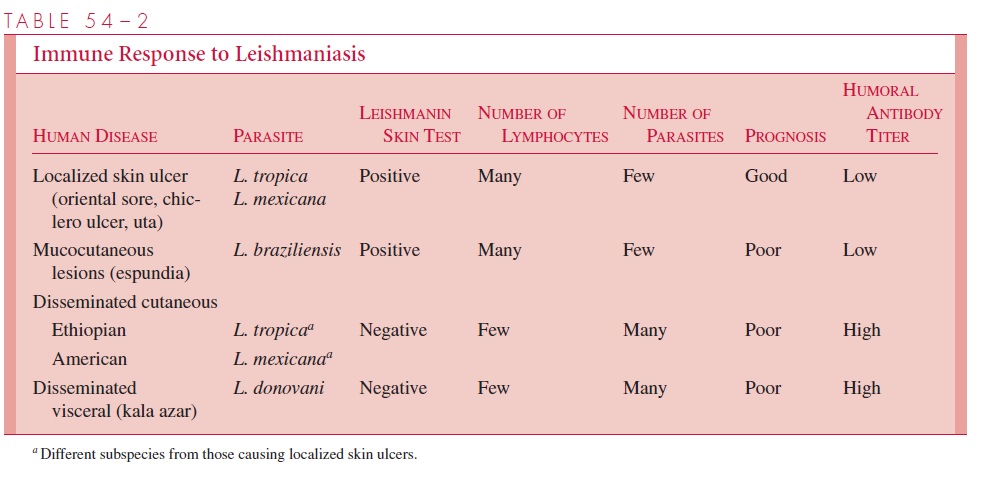

Continuation of this cycle results in extensive histiocytic proliferation. The course of the disease at this point is determined by the species of parasite and the response of the host’s T cells. CD4+ T cells of the TH1 type secrete interferon- γ in response to leishma-nial antigens. This, in turn, activates macrophages to kill intracellular amastigotes by the production of toxic nitric oxide. In the localized cutaneous forms of leishmaniasis, this immune response results in the development of a positive delayed skin (leishmanin) reaction, lymphocytic infiltration, reduction in the number of parasites, and, eventually, spontaneous disappearance of the primary skin lesion.

In infections with L. braziliensis, this sequence may be followed weeks to months later by mucocutaneous metastases. These secondary lesions are highly destructive, presumably as a result of the host’s hyper-sensitivity to parasitic antigens.

Some strains of L. tropica and L. mexicana fail to elicit an effective intracellular im-mune response in certain hosts. Such patients appear to have a selective suppressor T lymphocyte – mediated anergy to leishmanial antigens. Consequently, there is no infiltra-tion of lymphocytes or decrease in the number of parasites. The skin test remains nega-tive, and the skin lesions disseminate and become chronic (diffuse cutaneous leishmania-sis). In infections with L. donovani, there is a more dramatic inhibition of the TH1 response. The leishmanial organisms are able to disseminate through the bloodstream to the visceral organs, possibly because of a relative resistance of L. donovani to the natural microbicidal properties of normal serum, and/or their ability to better survive at 37°C than strains of Leishmania, causing cutaneous lesions. Although dissemination is associ-ated with the development of circulating antibodies, they do not appear to serve a protec-tive function and may, via the production of immune complexes, be responsible for the development of glomerulonephritis. A simplified outline of the immune responses in dif-ferent forms of leishmaniasis is presented in Table 54 – 2.

Related Topics