Chapter: Surgical Pathology Dissection : The Urinary Tract and Male Genital System

Kidney : Surgical Pathology Dissection

Kidney

General Comments

The

gross examination plays an important role in the evaluation of kidney

specimens. Macroscopic features often provide important clues to the underlying

pathologic process. For example, the accurate pathologic staging of renal neoplasms

can usually be accomplished simply by noting relationships between the tumor

and certain anatomic landmarks. As with other tissues, no kidney specimen

should be dissected without prior knowledge of the patient’s clinical history.

This fundamental rule is especially important when handling kidney specimens in

which the evaluation of glomerular disease relies on im-munofluorescence and

ultrastructural analysis. Thus, before processing even the smallest kid-ney

biopsy, determine from the clinical history whether fresh tissue should be

submitted for these special studies.

Biopsies

Electron

microscopy and immunofluorescence studies are central to the diagnostic

evaluation of kidney biopsies for non-neoplastic disease. Even small specimens

must be properly oriented because glomeruli should be included in the tissue

submitted for each of these tests. The goal of orienting kidney biopsies is to

distinguish cortex from medulla. While this distinction is usually quite simple

with the larger wedge biop-sies, the identification of cortex and medulla in

small-needle biopsies often requires the use of a magnifying lens or dissection

microscope. Under magnification, the cortex can be recognized byits red

sunburst pattern corresponding to the vascular tufts of the glomeruli. In

contrast, the straight vessels of the medulla are seen as thin red streaks

coursing through tan/white tissue. From the tips of the cortical end, freeze a

1-mm section for immunofluorescence, and submit an adjacent 1-mm section in

glutaraldehyde for elec-tron microscopy. If multiple cores are received, do the

same for each core. If you cannot confi-dently identify an end with cortex, do

not guess. Rather, submit 1-mm sections from both ends of the core. For larger

wedge biopsies, freeze a full-thickness section of cortex for

immunofluores-cence, and submit 1-mm3 cubes

from the cortex in glutaraldehyde for electron microscopy. Sub-mit the

remainder of the tissue in fixative for routine histologic processing.

Nephrectomies for Neoplastic Disease

The purpose

of evaluating kidneys resected for neoplasms is to determine the type of tumor,

its extent, and the completeness of the resection. This can easily be achieved

if you approach the nephrectomy as if it were made up of three individual

compartments: the kidney, the renal hilum, and the perinephric fat. Describe

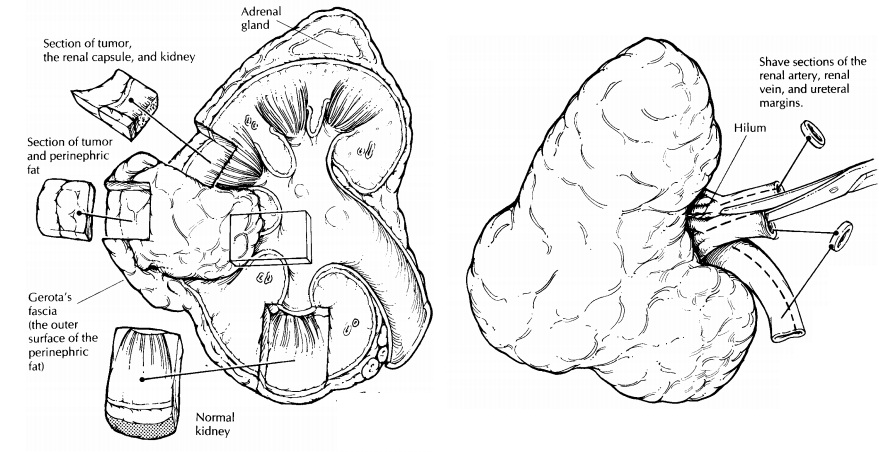

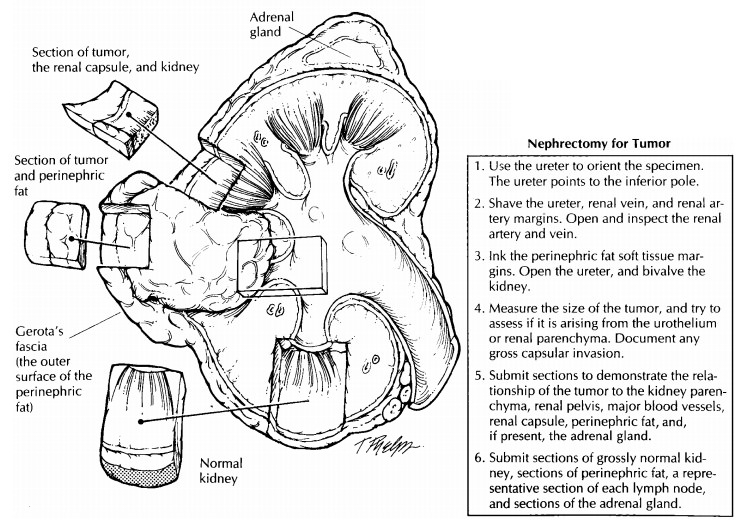

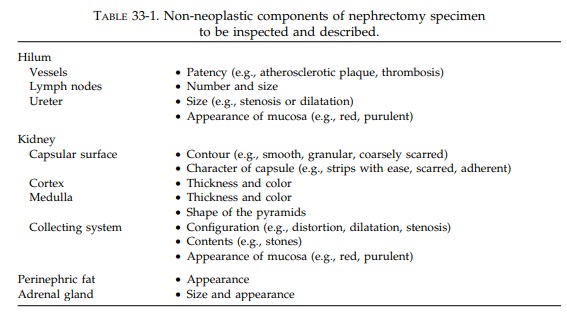

each component of the kidney individually and sys-tematically (Table 33-1).

First, weigh and measure the entire specimen. The renal capsule and the perinephric fat should not be stripped from the kidney until after their relationships to the tumor are established. Anat-omically orient the specimen. The ureter will provide a useful landmark: the downward course of the ureter points to the inferior pole of the kidney. By knowing whether the kidney is from the right or left side, you can easily iden-tify its anterior and posterior surfaces.

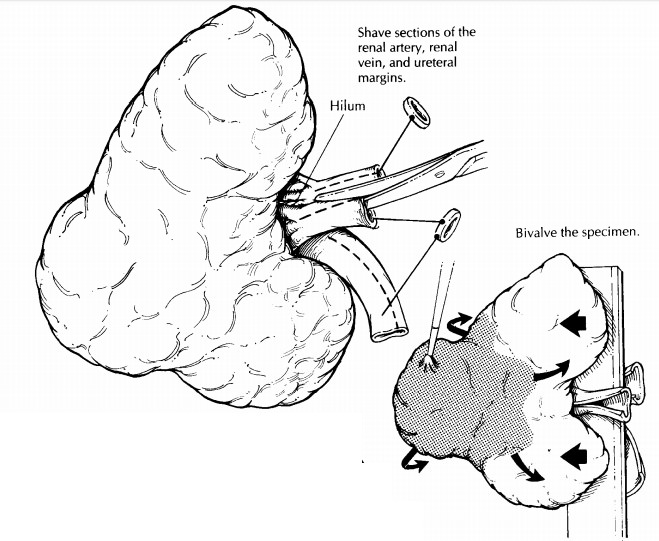

Begin

the dissection at the kidney hilum. Iden-tify the ureter, renal artery, and

renal vein. Shave the margin from each, and then open each with a small pair of

scissors to the point at which they enter the kidney. Look for the presence of

vas-cular invasion, atherosclerosis, and thrombosis. Carefully inspect the mucosa

and wall of the ureter. Is the ureter dilated or strictured? Are any masses

present? Occasionally, lymph nodes will be present in the soft tissues of the

hilum, and these should be individually measured and sam-pled. Other lymph node

groups are usually sub-mitted separately by the surgeon.

Next,

ink the soft tissue margins and direct your attention to the dissection of the

kidney itself. The objective of the initial section is to bivalve the kidney so

that the relationship of the tumor to the kidney can be easily visualized. The

plane of this initial section may vary de-pending on the location of the tumor,

but in gen-eral it will be a sagittal cut that begins at the hilum and exits

laterally through the perinephric fat. It may be helpful to insert probes into

the calyces of the upper and lower poles of the kid-ney to guide the knife

through the renal pelvis. Once the tumor is exposed, obtain fresh tissue for

special studies such as electron microscopy, immunofluorescence, and

cytogenetics, as is in-dicated. Describe the size, shape, color, and

con-sistency of the tumor. Does the tumor appearto be centered in the cortex,

medulla, or pelvis? Measure the distance of the tumor to the nearest margin,

and note its relationship to the peri-nephric fat, renal pelvis, renal vein,

ureter, and adrenal gland. Photograph the bivalved speci-men. At this point you

may choose to complete the dissection of the kidney in its fresh state, or you

may want to submerge the specimen in formalin until it is well fixed.

The

outer surface of the fat represents Gerota’s fascia. Ink this surface where it

overlies the tumor, and submit perpendicular sections to show the relationship

of the tumor to the soft tissue margin. Then carefully peel back the

peri-nephric fat from the kidney, examine the capsular surface, and look for

tumor extension through the renal capsule. Keep in mind that when renal tumors

invade through the capsule, they tend to bulge from the surface of the kidney.

Note any bulges, and document any disruption of the normal contour of the

kidney surface by submit-ting sections that include the tumor, the adja-cent

non-neoplastic kidney, and the overlaying capsule. Make additional sections

through the tumor and surrounding kidney. Look for any satellite tumors.

Submit

at least four sections of tumor (or more if necessary) to demonstrate the

relation-ship of the tumor to the kidney parenchyma, renal pelvis, major blood

vessels, renal capsule, and perinephric fat. Because some renal neo-plasms are

multifocal, section through the re-mainder of the kidney, looking for smaller

tumors. Do not forget to describe the cortex, medulla, and collecting system of

the non-neoplastic kidney. Also, submit one or two sec-tions of the

non-neoplastic kidney for histology. Finally, dissect the fibrofatty tissue

enveloping the kidney, and submit one or two sections of the fat to assess

infiltration by tumor.

Nephrectomy

specimens often will include the adrenal gland. Be sure to look for it in the

superior perinephric fat; if it is present, weigh it, measure it, and submit a

section. Keep in mind that the lymph nodes will be found in the soft tissues at

the kidney hilum. A misdirected search for lymph nodes in the perinephric fat

outside of the hilum will be a waste of your time.

Important Issues to Address in Your Surgical Pathology Report on Nephrectomies for Tumor

· What

procedure was performed, and what structures/organs are present?

· Is a

neoplasm present?

· Where is

the tumor located?

· How

large is the tumor?

· Does the

tumor invade the renal capsule, Gerota’s fascia, major veins, or the adrenal

gland?

· What are

the histologic type and grade of the neoplasm?

· What is

the status of each of the margins (ureter, renal vein, soft tissue)?

· Are

metastases identified? Record the number of nodes involved and the number

examined.

· Does the

non-neoplastic portion of the kidney show any pathology?

Partial Nephrectomies

Occasionally,

you may receive a partial nephrec-tomy—that is, a tumor removed with only a

small portion of surrounding renal parenchyma. Take the same approach as you

would for a total nephrectomy, only remember to sample the renal parenchymal

margins. Ink these margins, and submit perpendicular sections to demon-strate

the distance of the tumor’s edge to the margin. Given the much more limited extent

of these resections, you will often not be able toassess the relationship of

the tumor to the peri-nephric fat, renal vein, ureter, or other impor-tant

structures.

Nephrectomies for Non-neoplastic Disease

Dissection

of the nephrectomy specimen is essen-tially the same for neoplastic and

non-neoplastic diseases. Before beginning the dissection, try to establish from

the patient’s clinical history whether fresh cortical tissue should be taken

for immunofluorescence studies or electron micros-copy. Evaluate the kidney,

the hilum, and the perinephric fat as three separate compartments, using the

guidelines of dissection given earlier. When the specimen shows some

modification (e.g., the absence of a perinephric soft tissue compartment),

simply alter the dissection ac-cordingly. Some pathologists may prefer to

evaluate the texture of the cortical surface by stripping the capsule from the

fresh specimen, and this can be done before the kidney is sec-tioned and fixed.

If

calculi are identified during the dissection, submit some for chemical analysis

if indicated. Because the macroscopic findings often provide crucial clues to

the pathologic process involv-ing the kidney, describe each component of the

kidney individually and systematically (see Table 33-1).

Cystic Kidneys

Sometimes

kidneys are resected for congenital or acquired non-neoplastic cystic disease.

Even for massively enlarged and distorted kidneys, the dissection should follow

the same guidelines given above, only remember to pay particular attention to

the following points: (1) Probe the ureters before opening them to check for

patency.

•

Note the location of the cysts in terms of

their relationship to the cortex and medulla. (3) Docu-ment the size and

contents of the cysts. (4) Last, because cystic kidneys can harbor unsuspected

neoplasms, thoroughly section and inspect the kidney. Submit sections of any

suspicious areas, including solid foci, cysts with thickened walls, and cysts

with a papillary lining.

Related Topics