Chapter: Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing : Psychosocial Theories and Therapy

Interpersonal Theories

Interpersonal Theories

Harry Stack Sullivan: Interpersonal Relationships and Milieu Therapy

Harry Stack Sullivan (1892–1949) was an American psy-chiatrist who

extended the theory of personalitydevelopment to include the significance of

interpersonal relationships. Sullivan believed that one’s personality involves

more than individual characteristics, particularly how one interacts with

others. He thought that inadequate or nonsatisfying relationships produce

anxiety, which he saw as the basis for all emotional problems (Sullivan, 1953).

The importance and significance of interpersonal relationships in one’s life is

probably Sullivan’s greatest contribution to the field of mental health.

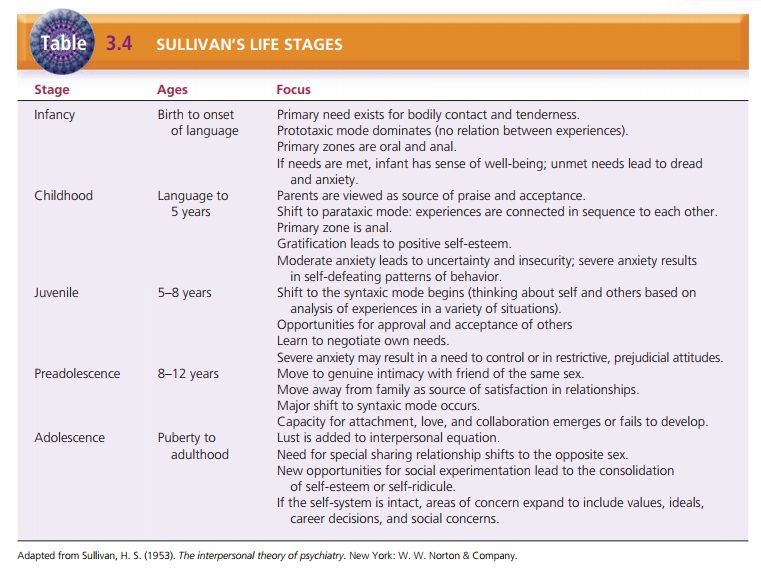

Five Life Stages. Sullivan established five

life stages of development—infancy, childhood, juvenile,

preadoles-cence, and adolescence, each focusing on various interper-sonal

relationships (Table 3.4). He also described three developmental cognitive

modes of experience and believed that mental disorders are related to the

persistence of one of the early modes. The prototaxic

mode, characteristic of infancy and childhood, involves brief, unconnected

experi-ences that have no relationship to one another. Adults with

schizophrenia exhibit persistent prototaxic experiences. The parataxic mode begins in early

childhood as the child begins to connect experiences in sequence. The child

maynot make logical sense of the experiences and may see them as coincidence or

chance events. The child seeks to relieve anxiety by repeating familiar

experiences, although he or she may not understand what he or she is doing.

Sullivan explained paranoid ideas and slips of the tongue as a per-son

operating in the parataxic mode. In the syntaxic

mode, which begins to appear in school-aged children and be-comes more

predominant in preadolescence, the person begins to perceive himself or herself

and the world within the context of the environment and can analyze

experi-ences in a variety of settings. Maturity may be defined as predominance

of the syntaxic mode (Sullivan, 1953).

Therapeutic Community or Milieu. Sullivan envisioned the goal of treatment as the establishment of satisfying inter-personal relationships. The therapist provides a corrective interpersonal relationship for the client. Sullivan coined the term participant observer for the therapist’s role, meaning that the therapist both participates in and ob-serves the progress of the relationship.

Sullivan is also credited with developing the first therapeutic community or milieu with

young men withschizophrenia in 1929 (although the term therapeutic com-munity was not used extensively until Maxwell Jones

pub-lished The Therapeutic Community

in 1953). In the concept of therapeutic community or milieu, the interaction

among clients is seen as beneficial, and treatment emphasizes the role of this

client-to-client interaction. Until this time, it was believed that the

interaction between the client and the psychiatrist was the one essential

component to the client’s treatment. Sullivan and later Jones observed that

interactions among clients in a safe, therapeutic setting provided great

benefits to clients. The concept of milieu

therapy, originally developed by

Sullivan, involved clients’ interactions

with one another, including practicing inter-personal relationship skills,

giving one another feedback about behavior, and working cooperatively as a

group to solve day-to-day problems.

Milieu therapy was one of the primary modes of treat-ment in the

acute hospital setting. In today’s health-care environment, however, inpatient

hospital stays are often too short for clients to develop meaningful

relationships with one another. Therefore, the concept of milieu therapy

receives little attention. Management of the milieu, or environment, is still a

primary role for the nurse in terms of providing safety and protection for all

clients and pro-moting social interaction.

Hildegard Peplau: Therapeutic Nurse–Patient Relationship

Hildegard Peplau (1909–1999; Figure 3.2) was a nursing the-orist

and clinician who built on Sullivan’s interpersonal theories and also saw the

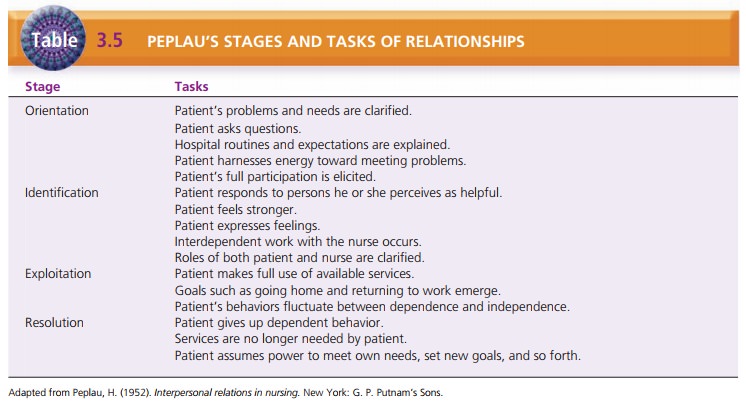

role of the nurse as a participant observer. Peplau developed the concept of

the therapeutic nurse–patient relationship, which includes four phases: orientation, identification,

exploitation, and resolution (Table 3.5).

During these phases, the client accomplishes certain tasks and

makes relationship changes that help the healing process (Peplau, 1952).

·

The orientation phase is

directed by the nurse and in-volves engaging the client in treatment, providing

ex-planations and information, and answering questions.

·

The identification phase

begins when the client works interdependently with the nurse, expresses

feelings, and begins to feel stronger.

·

In the exploitation phase,

the client makes full use of the services offered.

In the resolution phase,

the client no longer needs pro-fessional services and gives up dependent

behavior. The relationship ends.

Peplau’s concept of the nurse–client relationship, with tasks and

behaviors characteristic of each stage, has been modified but remains in use

today .

Roles of the Nurse in the Therapeutic

Relationship. Peplau also wrote about the roles of the nurse in the

therapeutic relationship and how these roles help meet the client’s needs. The

primary roles she identified are as follows:

·

Stranger––offering the client the same

acceptance and courtesy that the

nurse would to any stranger;

·

Resource person––providing specific answers to

ques-tions within a larger context;

·

Teacher––helping the client to learn

formally or informally;

·

Leader––offering direction to the

client or group;

·

Surrogate––serving as a substitute for

another such as a parent or sibling;

·

Counselor––promoting experiences leading

to health for the client such as

expression of feelings.

Peplau also believed that the nurse could take on many other roles,

including consultant, tutor, safety agent, medi-ator, administrator, observer,

and researcher. These were not defined in detail but were “left to the

intelligence and imagination of the readers” (Peplau, 1952, p. 70).

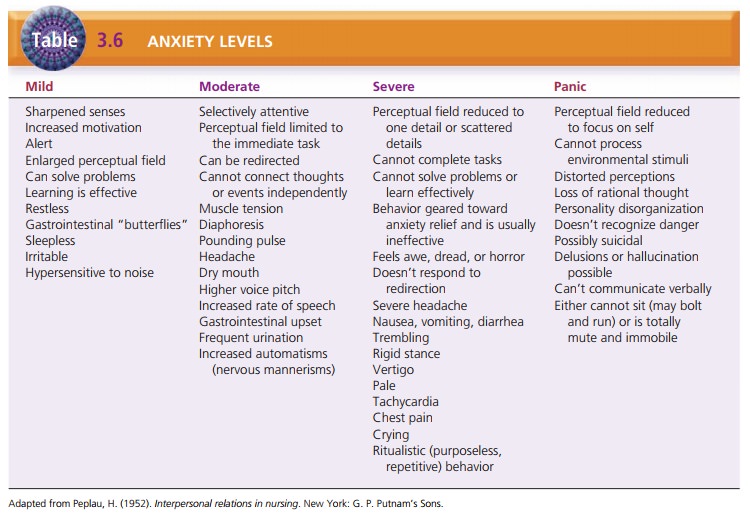

Four Levels of Anxiety. Peplau defined anxiety as the

ini-tial response to a psychic threat. She described four levels of anxiety:

mild, moderate, severe, and panic (Table 3.6). These serve as the foundation

for working with clients with anxiety in a variety of contexts .

1.

Mild anxiety is a positive state of

heightened awareness and sharpened

senses, allowing the person to learn new behaviors and solve problems. The

person can take in all available stimuli (perceptual field).

2.

Moderate anxiety involves a decreased

perceptual field (focus on immediate

task only); the person can learn new behavior or solve problems only with

assistance. Another person can redirect the person to the task.

3. Severe anxiety involves feelings of dread or terror. The person cannot be redirected to a task; he or she focuses only on scattered details and has physiological symptoms of tachycardia, diaphoresis, and chest pain. A person with severe anxiety may go to an emergency department, believing he or she is having a heart attack.

4. Panic anxiety can involve loss of rational thought, delu-sions, hallucinations,

and complete physical immobil-ity and muteness. The person may bolt and run

aimlessly, often exposing himself or herself to injury.

Related Topics