Chapter: Pharmaceutical Drug Analysis: Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy

Important Aspects of Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy

IMPORTANT ASPECTS OF ATOMIC ABSORPTION SPECTROSCOPY

The following three

important aspects of atomic absorption spectroscopy shall be discussed here

briefly, namely :

(i) Analytical

Techniques,

(ii) Detection

Limit and Sensitivity, and

(iii)

Interferences.

1. ANALYTICAL TECHNIQUES

In atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) the technique

using calibration curves and the standard addition method are both equally suitable for the quantitative

determinations of elements.

1.1. Calibration Curves

Theoretically, the absorbance must be proportional to

concentrations, however, deviations from lin-earity usually take place.

Therefore, it is necessary to prepare an empirical

calibration curve (ECC). For this, the standard solutions of the element(s)

to be determined are employed to plot the ECC from which the contents in the ‘test solutions’ may be measured

conveniently.

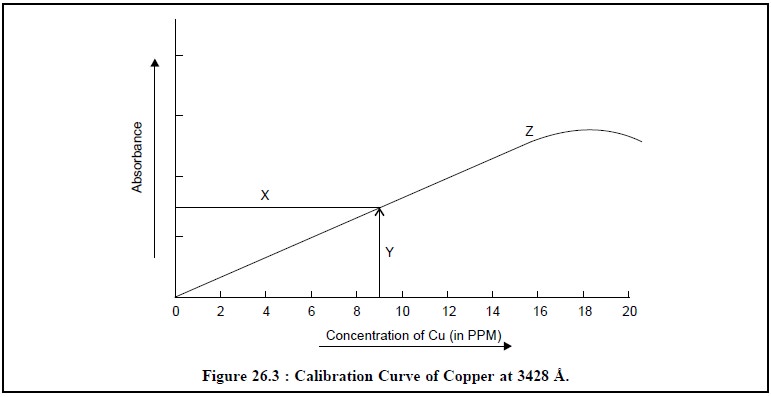

Figure 26.3, represents the typical calibration curves of

copper at 3428 Å, where :

X = Sample absorption reading,

Y = Sample concentration reading, and

Z = Calibration curve.

It is quite evident from the calibration curve (Z) in

Figure 26.3, that the linearity between the concen-tration of Cu (in ppm) and

absorbance prevails over the range 2.0 to 10.0 ppm specifically, whereas at

higher concentrations the said relationship does not hold good anymore. Hence,

it is pertinent to mention here that whenever the quantitative analysis of an

element is to be carried out, the absorbance is preferably measured almost

under the same experimental parameters whereby the calibration curve was

initially constructed.

1.2. Standard Addition Method

The standard

addition method is widely employed in AAS. In this case, two more aliquots

of the sample are transferred to volumetric flasks. The first, is diluted to

volume, and the absorbance of the solution is measured. The second, receives a

known quantity of analyte, whose absorbance is also measured after dilution to

the same volume. Likewise, data for other standard additions may also be

obtained.

If a plot between absorbance and concentration reveals a

linear relationship, which may be accom-plished by several stepwise standard

additions, the following expressions hold good, namely :

AX = k

CX …………………………(a)

AT = k

(CS + CX) …………………………(b)

where, CX = Analyte concentration in the diluted sample,

CS = Contribution of the added standard to the

concentration, and

AX and AT = Measured absorbances of

CX and CS.

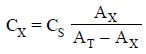

Combining Eqs. (a)

and (b) we have :

..........................(c)

..........................(c)

When a number of stepwise additions are performed, AT

can be plotted against CX. Thus, the resulting straight line may be

extrapolated to AT = 0. By substituting this value in Eq. (c) we may have at the intercept :

...........................(d)

...........................(d)

Advantage : The major plus points of the

standard addition method is that it tends to compensate for variations caused by physical and chemical interferences in the

sample solution.

2. DETECTION LIMIT AND SENSITIVITY

Detection Limit : It may be defined as the

concentration (meg ml–1) of an element that gives rise in the shifting of absorbance signal to

an amount which equals to the peak-to-peak noise of the base-line.

Sensitivity : It may be defined as the

concentration of element present in the sample solution that produces 1% absorption.

From the above definition it is quite evident that the

sensitivity takes no cognizance of the noise-level of the base-line, therefore,

it is more or less of no use as a definite guide to the least quantity of an

element which may be estimated. However, the sensitivity of a 1% absorption-is

a pure theoretical number only that would undergo a change solely depending on

the efficiency of the lamp (hollow-cathode-lamp), atomizer, flame-system

employed, monochromator (prism, grating used), and finally the photomultiplier

used.

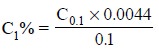

The sensitivity for 1% absorbance is determined by the

help of the expression given below :

where,

C1% = Concentration that yields 1% absorption,

and

C0.1 = Concentration that yields an absorption

of 0.1

Sensitivity is usually expressed in terms of mcg ml–1

for 1% absorbance.

It is an usual practice to perform an actual-test-run

over a sufficiently large range by employing the necessary prevailing expansion

facility so as to ascertain fully whether or not the atomic absorption

tech-nique is reasonably applicable to a specific low-level estimation. Such a

data may ultimately reveal the exact and true detection limit which is normally

equals to twice the noise level.

3. INTERFERENCES

In general, atomic absorption methods are subject to three types of interferences, namely :

(i) Spectral

Interferences,

(ii) Chemical

Interferences, and

(iii)

Ionisation Interferences.

The different interferences shall be discussed briefly

below :

3.1 Spectral Interferences

This type of interference normally takes place when the

absorption of an interfering species either overlaps or lies very near to the

analyte absorption, with the result that resolution by the monochromator almost

becomes impossible, Hollow-cathode-source invariably give rise to extremely

narrow emission-lines, hence interference caused due to overlap of atomic

spectral lines is rather rare.

A few typical examples of spectral interferences are

given below :

(a) Spectral

interferences caused either by the combustion products which show broad-band

absorp-tion or the particulate products which scatter radiation. In fact, both

these products distinctly lower the power of the transmitted beam of light and

ultimately give rise to positive analytical errors.

Remedy

(a) When the

source of the combustion or particulate products is the full and oxidant

mixture alone, then a blank is aspirated into the flame and the necessary

corrections are effected from the observed absorbances.

(b) Spectral

interferences may be produced due to an emission line of another element,

radical or molecule and also by unresolved band spectra. Here, the lines are

read together proportionately to the extent of overlap if the spectral band

after passing through the monochromator allows the undersired radiation to

reach the photoreceptor finally.

For instance : Manganese triplet (at 4031°,

4033° and 4035° A) : potassium doublet (at 4044° and 4047° A) and the gallium line (at 4033° A).

Remedy : The overlapping of this nature

may be eliminated either by prior chemical separation or by selection other spectral lines.

(c) Sample Matrix : A relatively more

complex and troublesome problem is usually faced when the source of scattering

originates right in the sample matrix itself. In such a situation, it has been

noticed that the power of the transmitted beam-designated as P, is reduced by

the nonanalyte components, whereas the incident beam power-designated as Po, is

not ; thereby resulting in a positive error in absorbance and hence in

concentration.

Example : Determination of Barium in

alkaline-earth mixtures affords a potential matrix interference due to absorption. It has been

observed that an intense and useful absorption line for barium atoms, occurring

at 553.6 nm, lies in the centre of a broad absorption band for Ca (OH)2,

that extends from 540 to 560 nm.

Remedy : (1) The effect due to sample

matrix is quickly and effectively eliminated by replacing nitrous oxide for air as the oxidant for the acetylene, whereby

the higher temperature completely decomposes the Ca (OH)2 and

eliminates the absorption band.

(2) If the source of interference is known, an excess of

the interfering substance may be added to the sample as well as the standards ;

provided the ‘excess’ is sufficient enough with respect to the concentration

from the sample matrix, the concentration of the latter will thus become

insignificant. Such an added sub-stance is sometimes referred to as a radiation

buffer.

3.2. CHEMICAL INTERFERENCES

In usual practice, the chemical interferences are found

to be more common than the spectral interfer-ence. However, their effects may

very often be minimized by appropriate choice of experimental parameters.

Examples : (i) Chemical Interferences

due to Anion (PO43–) : Phosphate ions have been found

to interfere with determination of

Mg and Ca by AAS. The absorption due to Mg and Ca are appreciably weaker in the

presence of PO43– ions than in their absence. This is

evidently on account of the formation of fairly stable phosphates of Mg and Ca

which do not readily split-up into the respective atoms in the mantle of a

flame.

Remedy : The addition of an excess of

strontium (Sr), or lanthanum (La), or thorium (Th) ion remark-ably minimizes

the interference of PO43– ion in the determination of Mg,

and Ca by replacing the analyte in the analyte in the compound formed with the

respective interfering species. In short, these ions do combine preferentially

with PO43– ions.

(ii) Chemical Interference due to Cations :

In certain specific cases cations also interfere in atomic absorption

measurements, for instance : Boron interferes with Mg and Ca ; whereas

aluminium interferes with alkaline earth elements.

Protective Agents : These agents are found to

inhibit the interferences by virture of their ability to form relatively stable but volatile species with the respective

analyte. There are three reagents

that are em-ployed commonly for this purpose, namely :

(a)

Ethylenediaminetetra-acetic acid (EDTA).

(b)

8-Hydroxyquinoline, and

(c) Ammonium

salt of 1-pyrrolidinecarbodithioic acid (APDC). EDTA helps to eliminate the

inter-ferences of Al3, Si4+, PO43–

and SO42– in the determination of Ca.

3.3. Ionization Interferences

It has been observed that the ionization of atoms or

molecules is comparatively very small in magni-tude in combustion mixtures

which essentially involve air as the oxidant and, therefore, may be ignored and

neglected. Consequently, the substitution of air with either oxygen or nitrous

oxide, however, gives rise to temperatures which are high enough to cause

appreciable ionization., Hence, as a consequence of the at-tained equilibrium-a

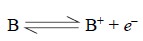

fairly significant concentration of electron exists as shown below :

where, M = Neutral atom or molecule,

M+ = Its corresponding ion, and

e– = An electron

Hence, if the medium has the species B in addition to

species M, and if the former ionizes according to the following equation :

then the extent of ionization of the latter will be

minimized substantially be the Law of

Mass Action of the electrons originated from the former species (i.e., B).

Example : The intensity of atomic

absorption lines for the alkali metals, such as : potassium (K) ; rubidium (Rb) ; and caesium (Cs), is

found to be affected by temperature in a complex way. Under certain

experimental parameters a noticeable decrease in absorption may be observed in

hotter flames. Hence, lower excitation temperatures are invariably recommended

for the analysis of alkali metals.

Remedy : The resulting effects of

shifts in ionization equilibrium may be eliminated effectively by the addition of an ionization

suppressor, that promptly gives a comparatively high concentration of electrons

to the flame. This ultimately results in the suppression of ionization by the

respective analyte.

Related Topics