Chapter: Medicine and surgery: Cardiovascular system

Heart failure - Cardiac failure

Cardiac failure

Heart failure

Definition

Heart failure is a complex syndrome that can result from any cardiac disorder (structural or functional) resulting in a failure to maintain sufficient cardiac output to meet the demands of the body. The clinical syndrome of heart failure is characterised by breathlessness, fatigue and fluid retention.

Prevalence/incidence

900,000 cases in the United Kingdom; 1ŌĆō4 cases per 1000 population per annum.

Age

Average age at diagnosis 76 years.

Aetiology

The most common cause of heart failure in the United Kingdom is coronary artery disease (65%). Causes include

┬Ę myocardial dysfunction, e.g. ischaemic or hypertensive heart disease, cardiomyopathy.

┬Ę inadequate cardiac outflow, e.g. valvular regurgitation or aortic stenosis.

┬Ę cardiac arrhythmias, e.g. atrial fibrillation.

┬Ę inadequate ventricular filling, e.g. constrictive pericarditis, cardiac tamponade, tachycardias.

┬Ę increased demand, e.g. anaemia, thyrotoxicosis, PagetŌĆÖs disease, beriberi.

Pathophysiology

The mechanism by which the heart fails to deliver a sufficient cardiac output is dependent on the underlying cause.

In myocardial dysfunction there is an inability of the normal compensatory mechanisms to maintain cardiac output. These mechanisms include

┬Ę FrankŌĆōStarling mechanism in which increased preload results in an increase in contractility and hence cardiac output.

┬Ę myocardial hypertrophy with or without cardiac chamber dilatation, which increases the amount of contractile tissue.

┬Ę release of noradrenaline, which increases myocardial contractility and causes peripheral vasoconstriction.

activation of the reninŌĆōangiotensinŌĆōaldosterone system causes sodium and water retention resulting in increased the blood volume and venous return to the heart (preload).

Other causes of heart failure including valvular heart disease and cardiac arrhythmias may cause heart failure in the absence of myocardial dysfunction, conversely a patient may have objective evidence of ventricular dysfunction with no clinical evidence of cardiac failure.

Chronic pulmonary oedema results from increased left atrial pressure, leading to increased interstitial fluid accumulation in the lungs and therefore reduced gas ex-change, lung compliance and dyspnoea. It can be acutely symptomatic when lying flat (orthopnea) or at night (paroxysmal nocturnal dysnoea) due to redistribution of blood volume and resorption of dependent oedema.

Clinical features

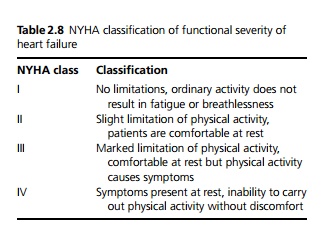

Clinically it is usual to divide cardiac failure into symptoms and signs of left and right ventricular failure, although it is rare to see isolated right-sided heart failure except in chronic lung disease. Grading of the severity of symptoms of heart failure is by the New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification (see Table 2.8).

Left-sided heart failure

Causes include myocardial infarction, systemic hyper-tension, aortic stenosis/regurgitation, mitral regurgitation, cardiomyopathy.

Symptoms: Fatigue, exertional dyspnoea, orthopnoea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea.

Signs: Late inspiratory fine crepitations at lung bases, third heart sound due to rapid ventricular filling and cardiomegaly at a late stage.

Right-sided heart failure

Causes include myocardial infarction, chronic lung disease (cor pulmonale), pulmonary embolism, pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary stenosis/regurgitation, tricuspid regurgitation and left-sided heart failure with resultant increase in pulmonary venous pressure.

Symptoms: Fatigue, breathlessness, anorexia, nausea, ankle swelling.

Signs: Raised jugular venous pressure, liver congestion causing hepatomegaly, pitting oedema of the ankles (or sacrum if patient is confined to bed).

Congestive cardiac failure is the term for a combination of the above, although it is often arbitrarily used for any symptomatic heart failure.

Investigations

Chest X-ray may show cardiomegaly. Chronic pulmonary oedema results in dilation of the pulmonary veins particularly those draining the upper lobes (up-per lobe vein diversion), pleural effusions and Kerley B lines (engorged pulmonary lymphatics). There may also be evidence of acute pulmonary oedema with ŌĆśbat wingŌĆÖ alveolar or ground glass shadowing.

ECG may demonstrate strain patterns or hypertrophy and underlying pathology such as a previous myocardial infarct. Cardiac arrhythmias may be present.

Echocardiography is used to assess ventricular function. It can demonstrate regional wall motion abnormalities, global dysfunction and overall left ventricular ejection fraction. Echocardiography can also show any underlying valvular lesions as well as demonstrating the presence of cardiomyopathy.

Other investigations that may be useful include radionuclide ventriculography and measurement of B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP).

Management

Patients require correction or control of underlying causes or contributing factors where possible, such as anaemia, pulmonary disease, thyrotoxicosis, hypertension, cardiac arrhythmias and infection. Ischaemic or valve disease often requires specific treatment.

Patients should be advised to stop smoking and reduce alcohol and salt intake. Weight loss and regular aerobic exercise should be encouraged. Patients with evidence of fluid overload should restrict their fluid intake to 1.5ŌĆō2 L/day.

Patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction have been shown to benefit from

┬Ę angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, which should be given to all patients even if asymptomatic. These should be used in conjunction with a diuretic if there is any evidence of peripheral oedema. Angiotensin II receptor antagonists may be used in place of ACE inhibitors in intolerant patients. They can also be used in addition to a combination of ACE inhibitors, ╬▓-blockers and diuretics in patients who remain symptomatic.

┬Ę ╬▓-blockers (bisoprolol, carvedilol or metoprolol) have been shown to reduce mortality in all patients with heart failure. They should be started at low dose and increased gradually.

┬Ę low-dose spironolactone, which improves prognosis in patients with moderate to severe heart failure (NYHA class III and IV). Patients require careful monitoring of renal function and potassium levels.

┬Ę digoxin, which is currently recommended for patients who remain symptomatic despite maximal treatment with other agents; however, in patients without atrial fibrillation there is no evidence of improved prognosis.

┬Ę other treatments including high-dose diuretics, biventricular pacing, left ventricular assist devices and cardiac transplantation. Anticoagulation should be considered in atrial fibrillation or with left ventricular thrombus. Automatic implantable cardiac defibrillator (AICD) have been shown to improve survival in patients with severe left ventricular dysfunction secondary to ischaemic heart disease. Statin lipid lowering drugs may be of benefit even in patients without ischaemic heart disease.

Patients with right ventricular dysfunction are treated symptomatically with diuretics and may benefit from ACE inhibitors.

Prognosis

Overall mortality is 40% in the first year after diagnosis, thereafter it falls to 10% per year.

Related Topics