Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Genetics Perspectives in Nursing

Genetics and Health Assessment - Applications of Genetics in Nursing Practice

GENETICS

AND HEALTH ASSESSMENT

Assessment of a person’s genetics-related health status is an on-going

process. The nurse collects information that can help identify individuals and

families who have actual or potential genetics-related health concerns or who

may benefit from further genetics information, counseling, testing, and

treatment. This process can begin before conception and continue throughout the

lifespan. Nurses evaluate family and past medical histories, in-cluding

prenatal history, childhood illnesses, developmental his-tory, adult-onset

conditions (if adult), past surgeries, treatments, and medications; this

information may relate to the genetic con-dition at hand or being considered.

The nurse also identifies the patient’s ethnic background and conducts a

physical assess-ment to gather pertinent genetics information. The assessment

also includes the patient’s culture, spiritual beliefs, and ancestry.

Genetics-related health assessment always includes determining a patient’s or

family’s understanding of actual or potential health concerns related to

genetics and understanding how these issues are communicated within a family

(ISONG, 1998; Lea, Jenkins & Francomano, 1998).

Family History Assessment

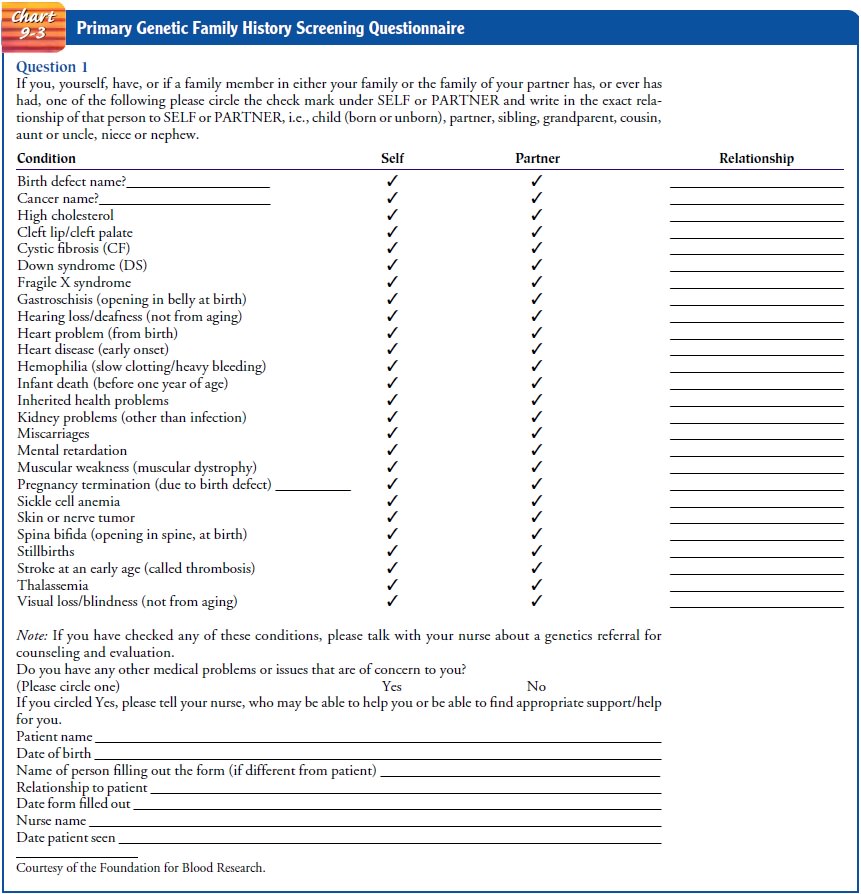

Nurses in any practice setting continuously assess genetic family

history to identify the presence of a genetic trait, inherited con-dition, or

predisposition. A questionnaire (Chart 9-3) is often used to identify genetic

conditions for which further information, ed-ucation, testing, or treatment can

be offered. In consultation and collaboration with other health care providers

and specialists, the nurse can then determine whether further genetic testing

and evaluation should be offered for the trait or condition in question. A

detailed and accurate family history provides the most com-plete genetics

health information. The family history should in-clude at least three

generations, as well as information about the current and past health status of

all family members, including the age of onset of any illnesses and cause of

death and age at death. The nurse also inquires about medical conditions known

to have a heritable component and for which genetic testing may be of-fered.

The nurse obtains information about the presence of birth defects, mental

retardation, familial traits, or similarly affected fam-ily members (Lashley,

1998; Lea, Jenkins & Francomano, 1998).

The nurse also considers the presence of genetic relatedness

(consanguinity) among family members when assessing the risk for genetic

conditions in couples or families. For example, when obtaining a preconception

or prenatal family history, the nurse asks whether the prospective parents have

common ancestors (ie, they are first cousins). This is important to know

because indi-viduals who share ancestors have more genes in common than those

who are unrelated, thus increasing their chance for having children with an

autosomal recessive inherited condition such as cystic fibrosis. The number of

shared genes depends upon the de-gree of relationship. A parent and child, for

example, share half of their genes, while first cousins share one in eight of

their genes. Ascertaining genetic relatedness gives the nurse the opportunity

to offer additional genetic counseling and evaluation. It may also serve as an

explanation for families who have a child or individ-ual with a rare autosomal

recessive inherited condition (Lea, Jenkins & Francomano, 1998).

When the assessment of family history reveals that the patient has been

adopted, genetics-based health assessment becomes more challenging. The nurse

and health care team should makeall efforts to help the patient obtain as much

information as pos-sible about his or her biological parents, including their

ethnic backgrounds.

Questions regarding reproductive history (eg, history of mis-carriage or

stillbirth) are included in genetic family history health assessments to

identify possible chromosomal conditions. The nurse also inquires about any

history of family members with in-herited conditions or birth defects; maternal

health conditions such as type 1 diabetes, seizure disorder, or maternal PKU,

which may increase the risk for birth defects in children; and exposure to

alcohol or other drugs during pregnancy. Maternal age is also noted: women who

are 35 years or older who are considering pregnancy and childbearing or who are

already pregnant should be offered prenatal diagnosis (eg, testing through

amniocentesis) because of the association between advancing maternal age and

chromosomal abnormalities such as Down syndrome (Lea, Jenkins & Francomano,

1998).

Ancestry and Ethnicity Assessment

Assessing ancestry and ethnicity helps identify individuals and groups

who could benefit from genetic testing for carrier identi-fication, prenatal

diagnosis, and susceptibility testing. For exam-ple, carrier testing for sickle

cell anemia is routinely offered to individuals of African-American heritage,

while carrier testing for Tay-Sachs disease and Canavan disease is offered to

individuals of Ashkenazi Jewish descent. Professional organizations such as the

American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG, 2001) recommend that

relevant racial and ethnic populations be offered carrier testing. Recently,

ACOG and the American Col-lege of Medical Genetics (ACMG) recommended that all

cou-ples, particularly those of Northern European and Ashkenazi Jewish

ancestry, be offered carrier screening for cystic fibrosis (ACOG, 2001).

Ideally, carrier testing is offered before conception to allow persons who are

carriers to make reproductive decisions. Prenatal diagnosis is offered and

discussed when both partners of a couple are found to be carriers.

Inquiring about a patient’s ethnic background is also impor-tant when

assessing for susceptibilities to adult-onset conditions such as hereditary

breast or ovarian cancer. For example, a spe-cific BRCA1 cancer-predisposing

gene mutation seems to occur more frequently in women of Ashkenazi Jewish

descent. There-fore, asking about ethnicity can help identify persons with an

in-creased risk for certain cancer gene mutations (American Medical

Association, 2001).

The nurse assesses ancestry and ethnic background to identify

individuals who may have an underlying genetic condition that may affect the

safety and efficacy of certain medications or treatments. For example,

glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PD) is a common enzyme

abnormality that affects millions of people throughout the world, especially

those of Mediterranean, Southeast Asian, African, Middle Eastern, and Near

Eastern origin. G6PD is transmitted as a gene mutation on the X chromosome.

Individuals with a severe deficiency have chronic hemolytic anemia, while

others with a milder deficiency develop hemolytic anemia upon exposure to peroxide-producing

drugs, infection, exposure to naphthalene in mothballs, or inges-tion of the

fava (broad) bean (Lashley, 1998).

Assessment of ancestry and ethnic background is also impor-tant when considering drug metabolism. The ability to metabolize and eliminate certain medications depends upon acetylation in the liver by the enzyme N-acetyltransferase. Many different versions (polymorphisms) of the gene that codes for N-acetyltransferase exist, and these polymorphisms vary among ethnic groups. This is an important consideration, for example, when isoniazid (INH) is prescribed for the treatment of tuberculosis. Patients who are rapid or ultra-rapid metabolizers have a significantly higher risk for developing isoniazid-induced hepatitis; this is especially true for persons of Chinese and Japanese descent (Lashley, 1998).

Physical Assessment

Physical assessment may provide clues that a particular genetic

condition is present in an individual and family. Family history assessment may

offer initial guidance regarding the particular area for physical assessment.

For example, a family history of familial hypercholesterolemia would alert the

nurse to assess family members for symptoms of hyperlipidemias (xanthomas,

corneal arcus, abdominal pain of unexplained origin). As an-other example, a

family history of neurofibromatosis type I, an inherited condition involving

tumors of the central nervous system, would prompt the nurse to carry out a

detailed assess-ment of closely related family members. Skin findings such as

café-au-lait spots, axillary freckling, or tumors of the skin (neuro-fibromas)

would warrant referral for further evaluation, including genetic evaluation and

counseling (Lea, Jenkins & Francomano, 1998).

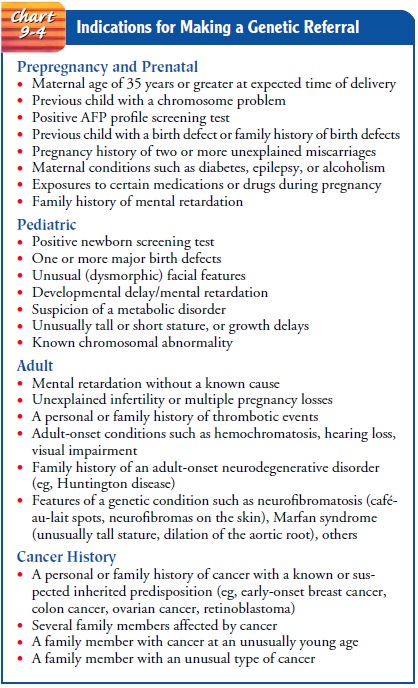

When a genetic condition

is suspected as a result of a family history or physical assessment, the nurse,

in collaboration with the health care team, may initiate further discussion and

evaluation. Providing genetics information, offering and discussing genetic

tests, and suggesting a referral to a geneticist may be performed (Chart 9-4).

Cultural, Social, and Spiritual Assessment

When collecting and discussing genetics information, the nurse needs to assess the patient’s and family’s cultural, social, and spir-itual orientations. The nurse also needs to consider the patient’s views about the significance of a genetic condition and its effect on self-concept, as well as the patient’s perception of the role of genetics in health and illness, reproduction, and disability. Pa-tients’ social and cultural backgrounds determine their interpre-tations and values about information obtained from genetic testing and evaluation and thus influence their perceptions of health, illness, and risk. Family structure and decision-making and educational background contribute in the same way (Lea, Jenkins & Francomano, 1998).

Assessing a patient’s beliefs, values, and expectations regard-ing genetic testing and information helps the nurse to provide appropriate information

about the specific genetics topic. In some cultures, for example, individuals

believe that health means the absence of symptoms and that the cause of illness

is supernatural. Patients with these beliefs may initially reject suggestions

for presymptomatic or carrier testing. However, by including re-sources such as

family, cultural, and religious community leaders when providing

genetics-related health care, the nurse can help ensure that patients receive

information in a way that tran-scends social, cultural, and economic barriers

(Lea, Jenkins & Francomano, 1998).

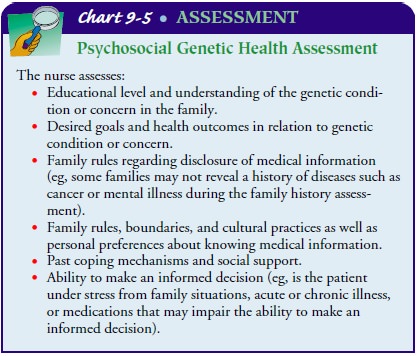

Psychosocial Assessment

Psychosocial assessment is an essential nursing component of the

genetics health assessment (Chart 9-5). After conducting an ini-tial

psychosocial assessment, the nurse will be aware of the po-tential impact of

new genetic information on the patient and family and how they may cope with

this information.

Related Topics