Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Anesthetic Management: Anesthesia for Ophthalmic Surgery

General Anesthesia for Ophthalmic Surgery

General Anesthesia for Ophthalmic Surgery

The choice between general and local

anesthesia should be made jointly by the patient, anesthesiolo-gist, and

surgeon. Patients may refuse to considerlocal anesthesia due to fear of being

awake during the operation, fear of the eye block procedure, or unpleas-ant recall

of a previous eye block or local eye proce-dure. General anesthesia is

indicated in children and uncooperative patients, as even small head move-ments

can prove disastrous during microsurgery.

PREMEDICATION

Patients undergoing eye surgery may be apprehen-sive, particularly if

they have undergone multiple procedures or there is a possibility of permanent

blindness. However, premedication must be admin-istered with caution and only

after careful consider-ation of the patient’s medical status. Adult patients

are often elderly, with myriad systemic illnesses, such as hypertension,

diabetes mellitus, and coro-nary artery disease. Pediatric patients may have

associated congenital disorders.

INDUCTION

The choice of induction technique for eye

surgery usually depends more on the patient’s other medical problems than on

the patient’s eye disease or the specific operation contemplated. One exception

isthe patient with a ruptured globe. The key to inducing anesthesia in a

patient with an openeye injury is controlling intraocular pressure with a

smooth induction. Specifically, coughing during intubation must be avoided by

achieving a deep level of anesthesia and profound paralysis. The intraocu-lar

pressure response to laryngoscopy and endotra-cheal intubation can be moderated

by prior administration of intravenous lidocaine (1.5 mg/kg) or an opioid (eg,

remifentanil 0.5–1 mcg/kg or alfen-tanil 20 mcg/kg). A nondepolarizing muscle

relax-ant or succinylcholine may be used. Despite theoretical concerns,

succinylcholine has not been shown to increase the likelihood of vitreous loss

with open eye injuries. Many patients with open globe injuries have full

stomachs and require a rapid-sequence induction technique because of the risk

of aspiration (see Case Discussion below).

MONITORING & MAINTENANCE

Eye surgery necessitates positioning the

anesthesia provider away from the patient’s airway, making close monitoring of

pulse oximetry and the cap-nograph particularly important. Endotracheal tube

kinking, breathing circuit disconnection, and unin-tentional extubation may be

more likely because of the surgeon working near the airway. Kinking and

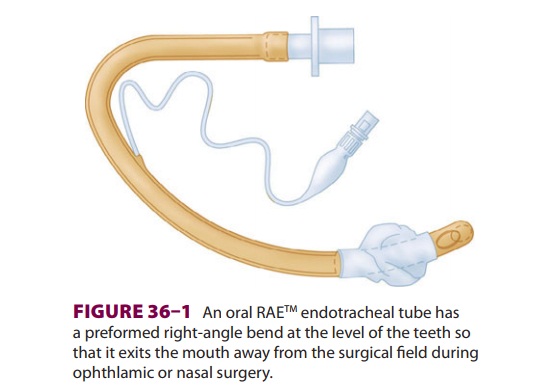

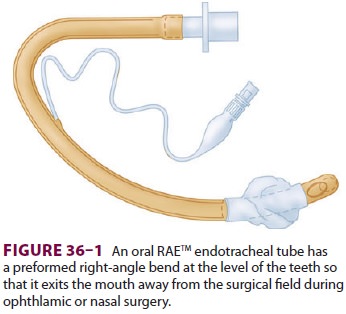

obstruction can be minimized by using a wire-rein-forced or preformed oral RAE® (Ring-Adair-Elwyn)

endotracheal tube (see Figure 36–1).

The possibil-ity of arrhythmias caused by the oculocardiac reflex increases the

importance of constantly scrutinizing the electrocardiogram (ECG) and making

sure that

the pulse tone is audible. In contrast to

most other types of pediatric surgery, infant body temperature may rise during

ophthalmic surgery because of head-to-toe draping and insignificant body

surface exposure. End-tidal CO 2 analysis helps to differenti-ate this phenomenon from malignant

hyperthermia.

The pain and stress evoked by eye surgery are considerably less than

during a major intraabdominal or intrathoracic procedure. A lighter level of

anesthe-sia would be satisfactory if the consequences of patient movement were

not so potentially catastrophic. The lack of cardiovascular stimulation

inherent in most eye procedures combined with the need for adequate anesthetic

depth can result in hypotension in elderly individuals. This problem is usually

avoided by ensur-ing adequate intravenous hydration and administer-ing small

doses of ephedrine or phenylephrine. The practice of substituting muscle

relaxation with non-depolarizing muscle relaxants for sufficient depth of

anesthesia requires constant attention to the level of neuromuscular blockade

to avoid patient movement, injury to the eye, and a malpractice claim.

Emesis caused by vagal

stimulation is a common postoperative problem following eye surgery,

partic-ularly with strabismus repair. The Valsalva effect and the increase in

central venous pressure that accom-pany vomiting can be detrimental to the

surgical result and will increase the risk of aspiration. Intraoperative

intravenous administration of a 5-HT3 antagonist (eg, ondansetron)

decreases the incidence of postopera-tive nausea and vomiting (PONV).

Dexamethasone (8–10 mg in adults) should also be considered for patients with a

strong history of PONV.

EXTUBATION & EMERGENCE

A smooth emergence from general anesthesia is

very important in order to minimize the risk of postop-erative wound dehiscence.

Coughing or gagging due to stimulus from the endotracheal tube can be minimized

by extubating the patient at a moderately deep level of anesthesia. As the end

of the surgical procedure approaches, muscle relaxation is reversed, and

spontaneous respiration is allowed to return. Anesthetic agents may be

continued during gentle suction of the airway. Nitrous oxide, if used, is then

discontinued, and intravenous lidocaine (1.5 mg/ kg) can be given to blunt

cough reflexes temporar-ily. Extubation proceeds 1–2 min after the lidocaineadministration

and during spontaneous respira-tion with 100% oxygen. Proper airway maintenance

is crucial until the patient’s cough and swallowing reflexes return. Obviously,

this technique is not appropriate in patients at increased risk of aspiration.

Severe discomfort is unusual following eye

sur-gery. Scleral buckling procedures, enucleation, and ruptured globe repair

are the most painful opera-tions. Modest incremental doses of intravenous

opi-oid (eg, fentanyl 25 mcg or hydromorphone 0.25 mg for an adult) usually

provide sufficient analgesia. The surgeon should be alerted if severe pain is

noted fol-lowing emergence from general anesthesia, as it may signal

intraocular hypertension, corneal abrasion, or other surgical complications.

Related Topics