Chapter: Essentials of Anatomy and Physiology: Body Temperature and Metabolism

Fever - Body Temperature

FEVER

A fever is an abnormally high body temperature and may accompany infectious diseases, extensive physical trauma, cancer, or damage to the CNS. The substances that may cause a fever are called pyrogens. Pyrogens include bacteria, foreign proteins, and chemicals released during inflammation. These inflammatory chemicals are called endogenous pyro-gens. Endogenous means “generated from within.” It is believed that pyrogens chemically affect the hypo-thalamus and “raise the setting” of the hypothalamic thermostat. The hypothalamus will then stimulate responses by the body to raise body temperature to this higher setting.

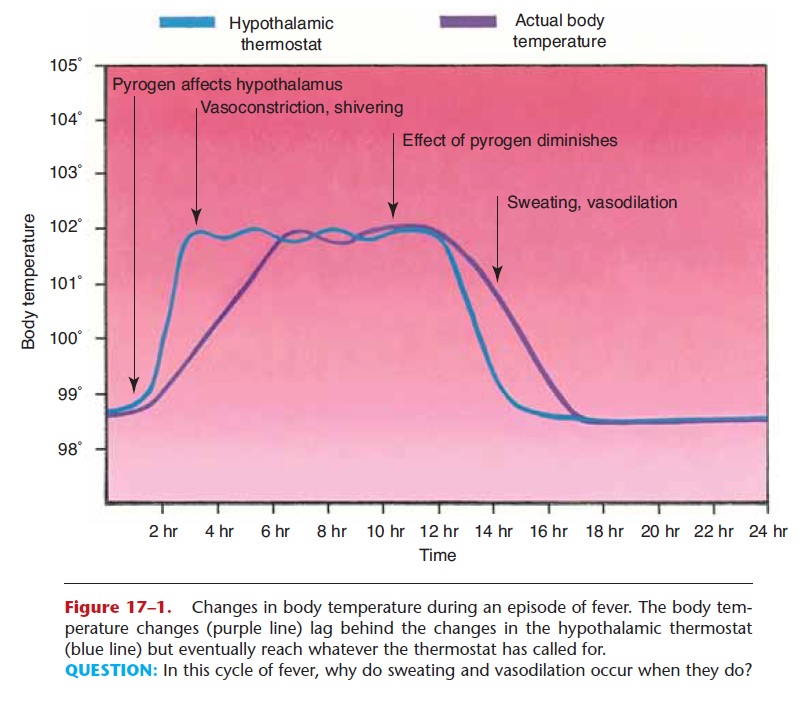

Let us use as a specific example a child who has a strep throat. The bacterial and endogenous pyrogens reset the hypothalamic thermostat upward, to 102°F. At first, the body is “colder” than the setting of the hypothalamus, and the heat conservation and produc-tion mechanisms are activated. The child feels cold and begins to shiver (chills). Eventually, sufficient heat is produced to raise the body temperature to the hypo-thalamic setting of 102°F. At this time, the child will feel neither too warm nor too cold, because the body temperature is what the hypothalamus wants.

As the effects of the pyrogens diminish, the hypo-thalamic setting decreases, perhaps close to normal again, 99°F. Now the child will feel warm, and the heat loss mechanisms will be activated. Vasodilation in the skin and sweating will occur until the body tempera-ture drops to the new hypothalamic setting. This is sometimes referred to as the “crisis,” but actually the crisis has passed, because sweating indicates that the body temperature is returning to normal. The sequence of temperature changes during a fever is shown in Fig. 17–1.

You may be wondering if a fever serves a useful pur-pose. For low fevers that are the result of infection, the answer is yes. White blood cells increase their activity at moderately elevated temperatures, and the metabo-lism of some pathogens is inhibited. Thus, a fever may be beneficial in that it may shorten the duration of an infection by accelerating the destruction of the pathogen.

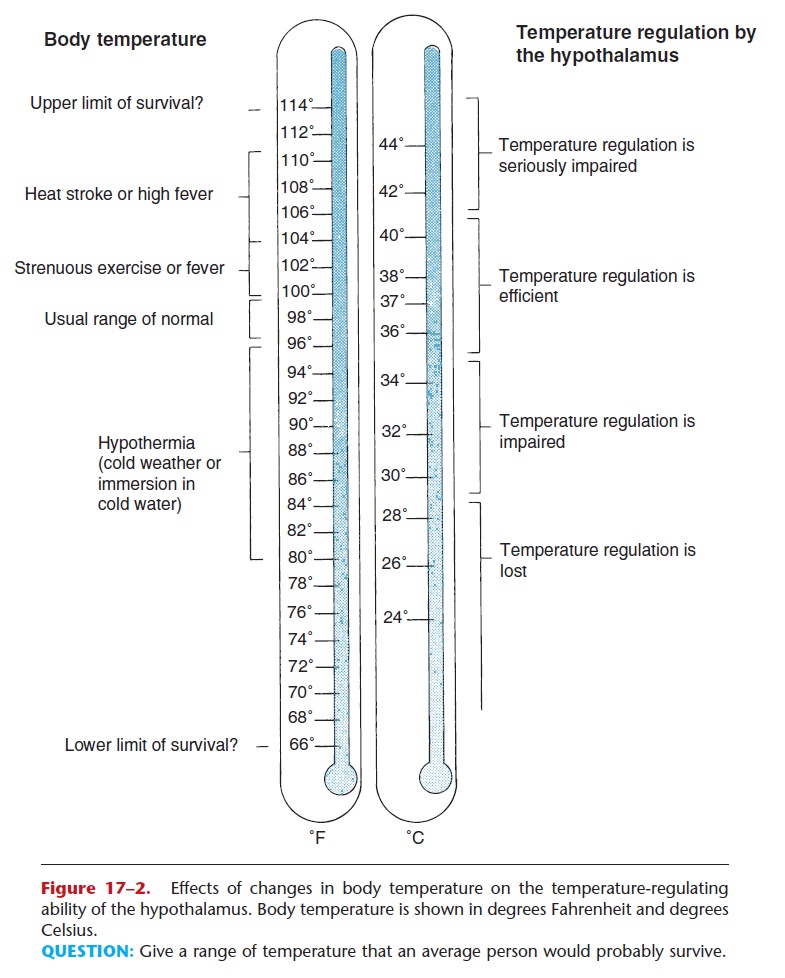

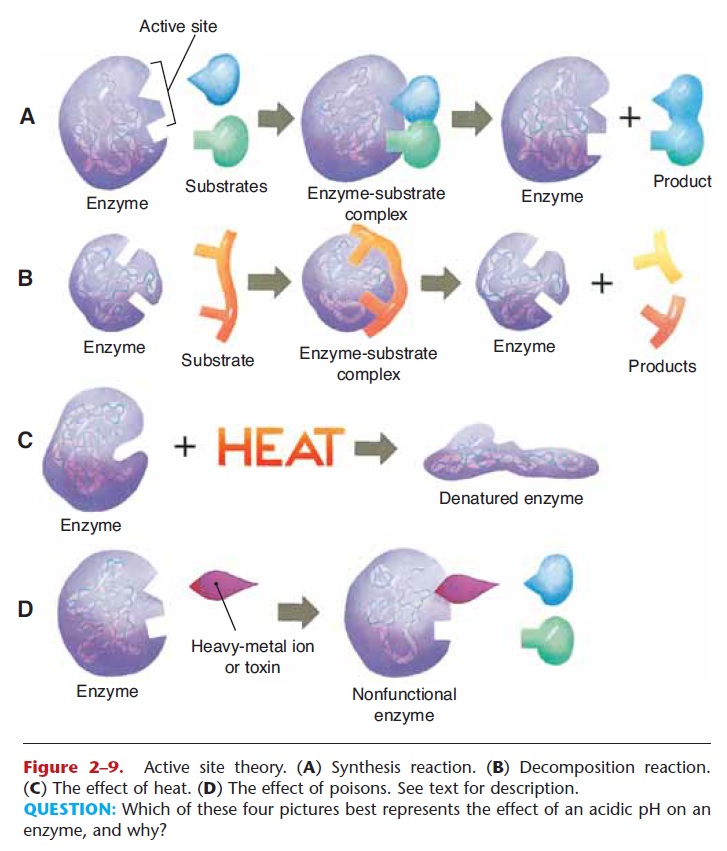

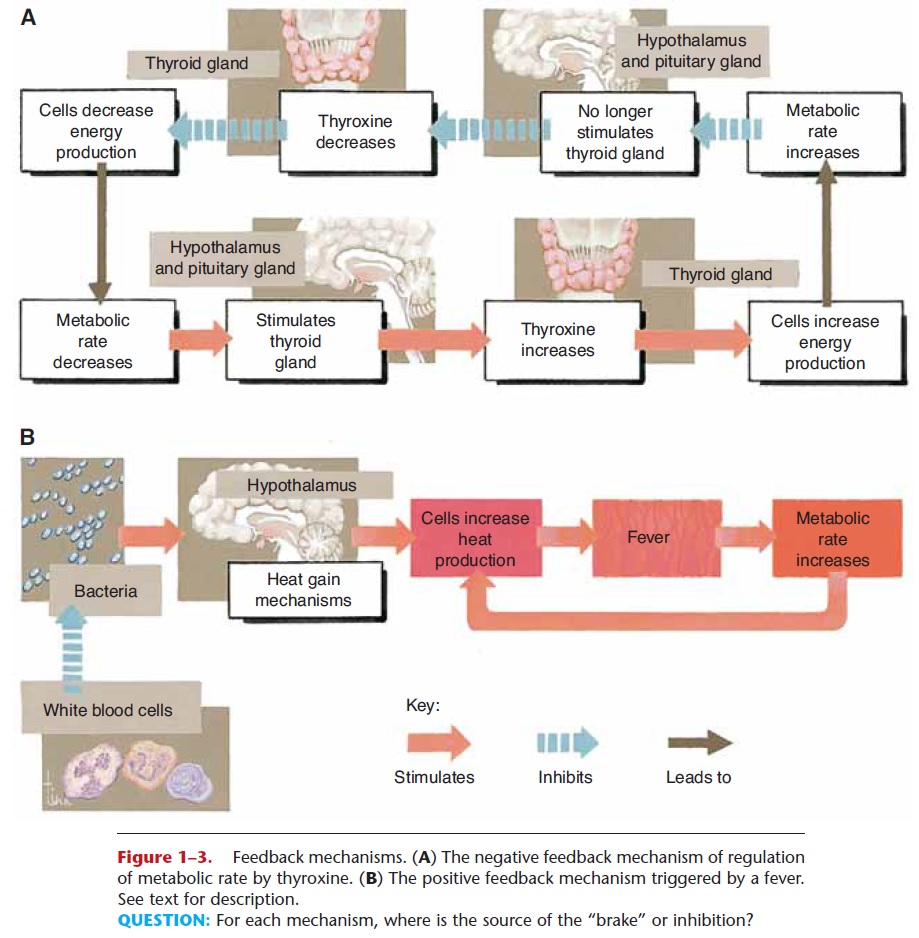

High fevers, however, may have serious conse-quences. A fever increases the metabolic rate, which increases heat production, which in turn raises body temperature even more. This is a positive feedback mechanism that will continue until an external event (such as aspirin or death of the pathogens) acts as a brake (see Fig. 1–3). When the body temperature rises above 106°F, the hypothalamus begins to lose its abil-ity to regulate temperature. The proteins of cells, especially the enzymes, are also damaged by such high temperatures. Enzymes become denatured, that is, lose their shape and do not catalyze the reactions nec-essary within cells (see Fig. 2–9). As a result, cells begin to die. This is most serious in the brain, because neurons cannot be replaced, and cellular death is the cause of brain damage that may follow a prolonged high fever. The effects of changes in body temperature on the hypothalamus are shown in Fig. 17–2.

A medication such as aspirin is called an anti-pyretic because it lowers a fever, probably by affecting the hypothalamic thermostat. To help lower a high fever, the body may be cooled by sponging it with cool water. The excessive body heat will cause this external water to evaporate, thus reducing temperature. A very high fever requires medical attention.

Related Topics