Chapter: Aquaculture Principles and Practices: Trouts and Salmons

Feeds and feeding of salmonids

Feeds and feeding of salmonids

Much of our present knowledge of fish nutrition and feed technology is

based on work carried out on salmonids.

Although there are many gaps in the basic information, a sizeable fish

feed manufacturing industry has developed as a result of this work and there is

an expanding demand for feed in trout and salmon farming, especially in Europe

and North America. Manufacturers do make separate feeds for salmon and trout,

but experience seems to suggest that they are interchangeable, although salmon

diets normally contain a higher percentage of animal protein.

Large-scale farming of trout started

in Denmark with the use of trash or industrial fish that was available at low

prices as feed. It continues to be used for both trout and salmon farming in

Scandinavian countries, even though there is now a greater use of processed

commercial feeds. The whole fish or waste left after filleting in processing

industries and fish silage are also used. Other fresh feeds, like

slaughter-house offals, have been used as feed in small-scale farming in other

parts of the world, but such material is not available in sufficient quantities

to sustain any large operations.

Species of white (non-oily) fish are preferred as salmonid feed, because

fish with a high fat content are more difficult to store and the fat soon

becomes rancid. Wet diets prepared with white fish have a low fat and high

protein content (approximately 5 per cent fat and over 80 per cent protein, dry

weight). It may therefore be necessary to add extra fat to the mixture, so that

part of the energy requirements of the fish can be met and more of the proteins

become available for growth. When species with somewhat higher fat contents are

used, it is not necessary to add extra fat. The most common industrial fish

used for salmon and trout feeding in Norway is the capelin (Mallotus villosus). Other fatty fish

used are sprats(Clupea) and sand eels

(Ammodytes). Fish of the herring

family are not used because of the presence of thiaminase which destroys

vitamin B1. It is necessary to add thiamin to the diet if the fish are fed with

raw herring or a diet containing herring meal.

Although some farmers in Norway feed the fish with whole capelin, the

general practice is to mince the fish with a binder to improve the consistency

and add vitamin and mineral mixes to ensure that there is no deficiency in the

essential trace elements. The protein content of whole fish is generally around

17–18 per cent of the wet weight. The commercially available binding meals,

which are mostly carbohydrate, contain 10 per cent or less protein and about 3

per cent fat. Meals containing 35–40 per cent protein are also available

commercially for adding to fresh food diets, which contain about 50 per cent

animal protein and about 7–10 per cent fat. Some formulations may contain the

necessary vitamins and minerals, in which case 5–10 per cent of this meal is

added; if not, only about 1 per cent is added to keep the food together and

reduce wastage. Shrimp waste is often added to give a distinctive pink colour

to the flesh of salmon and trout at the rate of 10 per cent of the diet, which

gives a concentration of about 5–6ppm of the pigment astaxanthin in the

prepared feed.

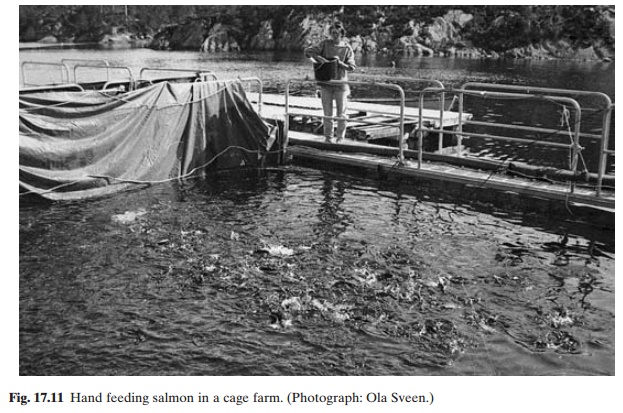

Special wet feed dispensers are available, but it is more common to feed

cage fish with wet feed by hand (fig. 17.11). If mechanical dispensers are

used, the feed should have a smoother consistency, suitable for extrusion

through a die. Most farmers feed their fish as often as possible, as they

believe that frequent feeding with small quantities, rather than occasional

feeding of large quantities, gives better growth rates. However, feeding once

or twice a day has been found to be equally satisfactory. Feed dispensers used

for wet feeds have been described. A type of feeder especially suited for

salmon and trout grown in tanks consists of a canister containing the food

mixture travelling on a track over the fish tanks. As it passes over each tank,

a piston expels a measured amount from a nozzle. Mobile dispensers have been

made from modified slurry tankers from which feed is forced out in a jet by

compressed air. Wet feed is also sometimes pumped along pipelines directly to

the race-ways or cages in large farm units. Very good wet feed mixtures give

conversion ratios of up to 5:1, but poorer qualities give only about 8:1.

Attempts have been made to reduce the percentage of animal protein in

salmonid diet. Soybean meal now forms 10–30 per cent of commercial diets, but

the quantity of fish meal is not reduced to less than 20 per cent. A choice of

pigmented or unpigmented feed is commercially available in larger pellet sizes.

Around 40–60ppm of the artificial carotenoid canthaxanthin or astaxanthin is

added to dry feed to give a darker red colour to salmonid flesh.

Pigmented feed is given for only three to six months, depending on

temperature, before the fish are harvested for slaughter. Many salmonid farmers

prefer to feed their fish with moist pellets that contain 20–50 per cent

moisture, as against 12 per cent moisture of dry pellets.

Salmon are usually fed high-energy feeds with high lipid content so the farmers can achieve a better feed conversion, but this ends in high adiposity in fishes, as is also shown in cod. Two groups of juvenile salmon whose body-fat contents were manipulated by feeding diets with differing fat contents – one having high fat content (9.4%) in the body and the other having low fat content (5.6%) – were fed simultaneously with lean (low-fat) and fatty (high-fat) content diets over a period of time. Though both groups preferred to feed on lean diet, the lean fish ate more and in course of time the fat content in the groups converged, approximating the same average body fat content, which suggests that there is a lipostatic regulation of feeding in juvenile salmon, as is also suspected in other fishes (Johansen et al., 2002).

Related Topics