Chapter: Basic Radiology : Musculoskeletal Imaging

Exercise: Systemic Disease

EXERCISE 6-3.

SYSTEMIC DISEASE

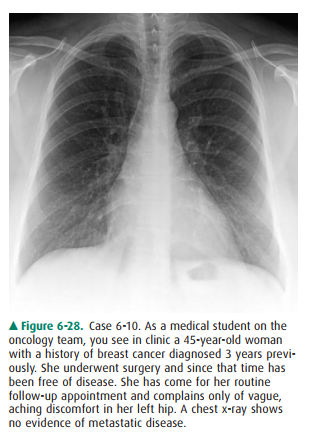

6-10. For Case 6-10

(Figure 6-28), which of the following studies would be least useful today?

A.

Chest CT

B.

Left hip x-ray

C.

Bone scan

D.

Skeletal survey

E.

Mammography

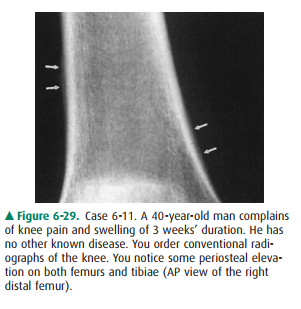

6-11. For Case 6-11

(Figure 6-29), what is the next study you should order?

A.

Bone scan

B.

MRI of the knee

C.

Hand films

D.

Chest radiograph

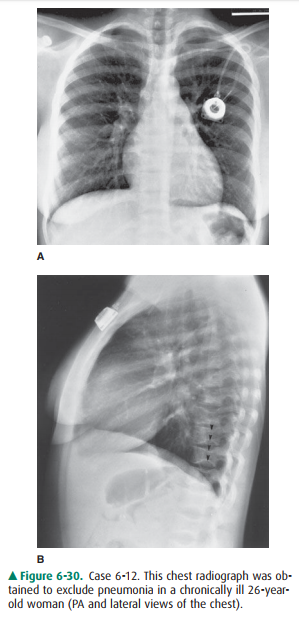

6-12. For Case 6-12

(Figure 6-30), there is no evidence of pneumonia, but there are several

abnormalities that are clues to the nature of this patient’s chronic illness.

Which finding is such a clue?

A.

The presence of a central venous line

B.

Enlargement of the pulmonary artery segment of the mediastinum

C.

Depression in the endplates of numerous vertebrae

D.

Asymmetry of the breast shadows

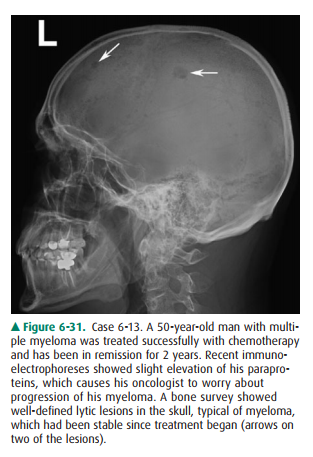

6-13. For Case 6-13

(Figure 6-31), which of the following imaging tests is most likely to help

determine if this patient has progressive myeloma?

A.

PET-CT

B.

Bone Scan

C.

Chest x-ray

D.

CT of the spine

Radiologic Findings

6-10. D is the correct

answer to Question 6-10.

6-11. A thin rim of

calcium added to the bony contour of both sides of the right femoral metaphysis

(Figure 6-29, arrows) is due to periosteal elevation. Similar findings were

present on the left femur and both tib-iae (D is the correct answer to Question

6-11).

6-12. Many vertebral

bodies, as best appreciated in the lat-eral view, are shaped like the letter H

(arrowheads), with central depressions in the superior and inferior end plates.

(Figure 6-30) (C is the correct answer to Question 6-12).

6-13. A is the correct

answer to Question 6-13.

Discussion

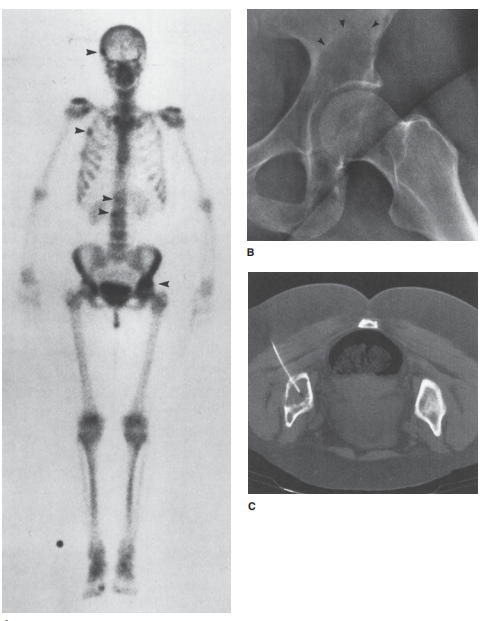

Case 6-10: Option E, mammography,

is a reasonable screen-ing examination. This would be a good test to order for

this patient even without new symptoms. Indeed, mammogra-phy should be obtained

in any woman of 45 years every year for screening purposes, irrespective of her

history. Bone scans are also often ordered as screens for metastatic diseasein

asymptomatic breast cancer patients, particularly for the first 2 to 3 years

after diagnosis. Because this patient is com-plaining of skeletal pain, both a

bone scan (Figure 6-32 A) and conventional radiographs of the affected area

(Figure 6-32 B) are indicated. A chest CT can be helpful to find small

pulmonary metastases that may not be apparent on a conventional chest radiograph.

Whether to order it for this woman may depend in part on the preferences of the

attend-ing oncologist and on risk factors such as the size of the orig-inal

tumor and nodal status at the time of diagnosis. Option D, a skeletal survey,

is inappropriate. Bone surveys are gener-ally utilized in breast cancer only

for follow-up of patients with widespread osseous metastatic disease.

In this patient’s case, a bone

scan revealed multiple areas of abnormally increased accumulation of

radionuclide, includ-ing the left acetabulum (Figure 6-32 A,B). The

multiplicity of lesions, together with the history of breast cancer (which

often metastasizes to bone and may do so after a disease-free inter-val of many

years), is very suggestive of metastatic disease. Some oncologists would choose

to treat the patient for pre-sumed metastatic disease on the basis of the bone

scan, his-tory, and current symptoms. Others would prefer a biopsy before

proceeding to further treatment. This patient under-went a CT-guided needle aspiration

of the acetabular lesion, which revealed metastatic tumor (Figure 6-32 C). To

evaluate for possible impending pathologic fracture (Figure 6-33), most

oncologists would also request conventional radi-ographs of areas demonstrating

increased activity on the bone scan, particularly those in weight-bearing

bones.

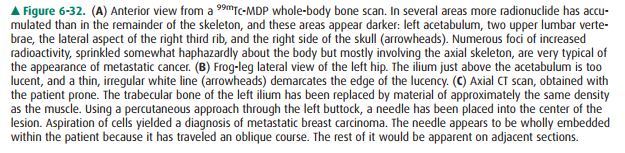

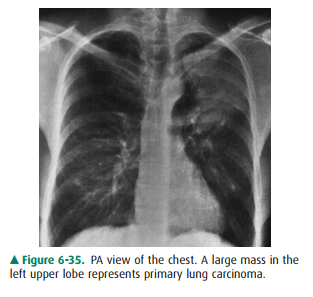

Case 6-11: Periosteal elevation

is a nonspecific finding that occurs with local disorders such as fracture,

bone tu-mors, and osteomyelitis and also with systemic or multifocal disorders

such as bone infarction (Figure 6-34), venous sta-sis, and secondary

hypertrophic osteoarthropathy. Because this finding is bilateral, it is more

likely due to a systemic or multifocal disorder than to a local one.

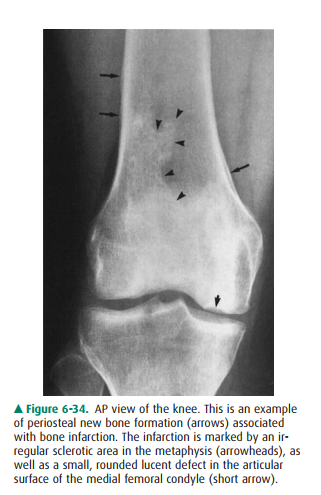

Of all systemic disorders that

may be associated with pe-riosteal new bone formation, secondary hypertrophic

os-teoarthropathy is the most important to exclude. At one time it was called

hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy be-cause it is usually caused by

pulmonary disease. The designa-tion secondary hypertrophic osteoarthropathy

reflects current understanding that this disorder may also be due to

nonpulmonary diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease or congenital cardiac

anomalies. Nonetheless, pulmonary disease, specifically lung cancer, remains

the most common cause. This patient, in fact, had lung cancer (Figure 6-35).

A bone scan could be useful if

you did not notice the pe-riosteal new bone or were not sure of its presence.

Hand films could demonstrate clubbing, which may be seen with some of the same

disorders that cause hypertrophic osteoarthropathy, but simple physical

inspection of the patient’s hands would accomplish the same thing. MRI of the

knees will not be helpful in this case.

Case 6-12: This patient (see

Figure 6-30) has sickle cell disease. The peculiar shape of multiple vertebral

bodies is very characteristic of sickle cell anemia, though it may

occa-sionally be seen in other diseases affecting the marrow cavity, particularly

Gaucher’s disease. It may be caused by infarction of bone beneath the

endplates, with remodeling of the cortex to produce the H-shape.

When red cells sickle, they clump

together and may block blood vessels. In bone this leads to avascular necrosis,

which may be widespread, involving many bones simultaneously. The mottled

appearance of this patient’s humeral heads is due to avascular necrosis and is

a common finding in patients with sickle cell anemia.

Though they were not included

among the possible answers to the question, there are other findings on this

examination that are clues to the diagnosis. The gas-filled splenic flexure of

the colon occupies too much of the left upper quadrant on the frontal view.

There is no room for a spleen of normal size. In sickle cell patients, the

spleen is often infarcted so that by any time they reach adulthood, it has

shrunk to a small fraction of normal size. People with sickle cell disease are

prone to early de-velopment of calcium bilirubinate gallstones (cholelithiasis).

Modest enlargement of the

pulmonary artery, as seen in this patient, is so common in young women that it

is consid-ered normal in that population. The central line may be seen in many

patients with a variety of disorders requiring chronic intravenous therapy.

Case 6-13: Multiple myeloma is a

disease that can never really be considered cured. The goals of therapy are

control ofsymptoms and, if possible, induction of remission. Remis-sion may

last months or even years, and during remission the patient is monitored for

any signs that the disease has re-turned and is progressing. In this patient’s

case, the oncolo-gists are looking for any imaging-based evidence of disease

progression to back up a fairly weak clinical indicator.

A challenge is that the patient

is already known to have lytic bone disease. Even though the myeloma has been

in re-mission, the lytic lesions will not have gone away. Therefore, imaging

studies that rely primarily on anatomy will only be helpful if they

unequivocally show evidence of new lytic le-sions. The bone survey has already

been asserted to be un-changed, so no other conventional radiographs are likely

to be helpful, either. Therefore, a chest x-ray will not be a good choice. CT

scans are also anatomically based tests and can be expected to show lytic

lesions without necessarily helping to determine if the lesions are old and

quiescent or if they are actively growing.

What is needed is a test that

will assess the metabolic ac-tivity of this patient’s multiple myeloma,

preferably with some associated anatomic information. MRI may be helpful in

such situations. It is a good anatomic test, and if contrast is given, it also

demonstrates areas of hyperemia. MRI, how-ever, was not one of the answer

choices. Bone scans are meta-bolic tests, but myeloma is a notorious source of

false negative bone scans.

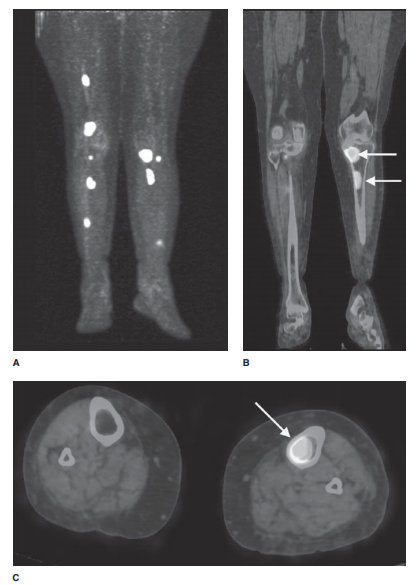

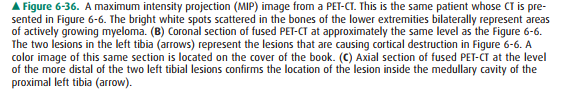

PET-CT may be quite useful for

differentiating quies-cent from metabolically active, growing lesions of

myeloma (Figure 6-36).

Related Topics