Chapter: Professional Ethics in Engineering : Engineering Ethics

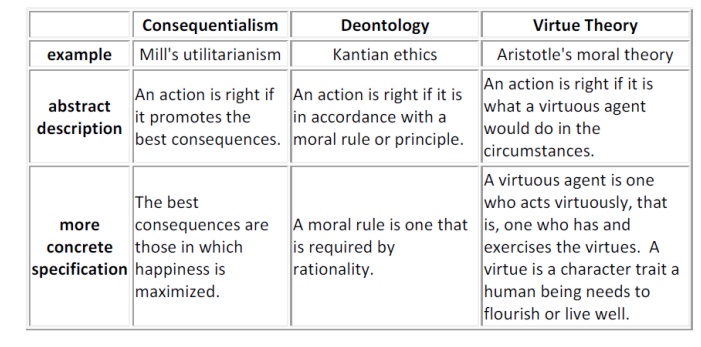

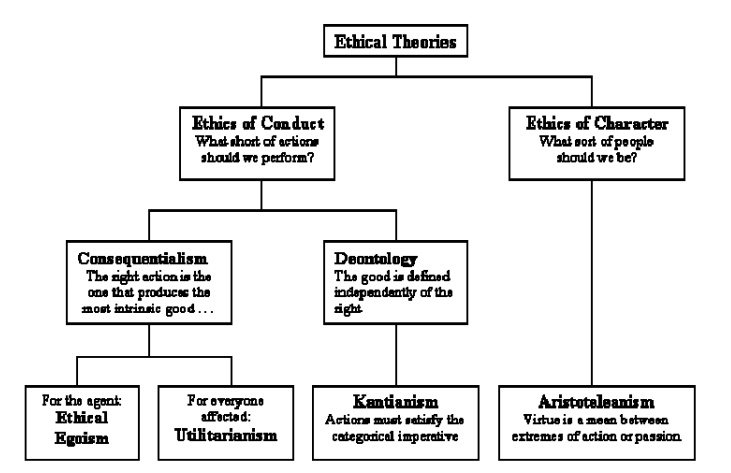

Ethical Theories

ETHICAL THEORIES:

Independently propounded ethical theories are many and are very

diverse in nature.

Philosophical point of view of ethical heories Deontology

Deontological ethics or deontology (from Greek

δέον, deon, "obligation, duty"; and - λογία, -logia) is an approach

to ethics that determines goodness or rightness from examining acts, or the

rules and duties that the person doing the act strove to fulfill. This is in

contrast to consequentialism, in which rightness is based on the consequences

of an act, and not the act by itself. In deontology, an act may be considered

right even if the act produces a bad consequence, if it follows the rule that

"one should do unto others as they would have done unto them", and

even if the person who does the act lacks virtue and had a bad intention in

doing the act. According to deontology, we have a duty to act in a way that does

those things that are inherently good as acts ("truth-telling" for

example), or follow an objectively obligatory rule (as in rule utilitarianism).

For deontologists, the ends or consequences of our actions are not important in

and of themselves, and our intentions are not important in and of themselves.

Immanuel Kant's theory of ethics is considered deontological for several

different reasons. First, Kant argues that to act in the morally right way,

people must act from duty (deon). Second, Kant argued that it was not the

consequences of actions that make them right or wrong but the motives (maxime)

of the person who carries out the action. Kant's argument that to act in the

morally right way, one must act from duty, begins with an argument that the

highest good must be both good in itself, and good without qualification.

Something is 'good in itself' when it is intrinsically good , and 'good without

qualification' when the addition of that thing never makes a situation

ethically worse. Kant then argues that those things that are usually thought to

be good, such as intelligence, perseverance and pleasure, fail to be either

intrinsically good or good without qualification. Pleasure, for example,

appears to not be good without qualification, because when people take pleasure

in watching someone suffering, this seems to make the situation ethically

worse. He concludes that there is only one thing that is truly good:

Nothing in the world—indeed nothing even beyond

the world—can possibly be conceived which could be called good without

qualification except a good will.

Kantian ethics:

Kantian ethics are deontological, revolving

entirely around duty rather than emotions or end goals. All actions are

performed in accordance with some underlying maxim or principle, which are

deeply different from each other; it is according to this that the moral worth

of any action is judged. Kant's ethics are founded on his view of rationality

as the ultimate good and his belief that all people are fundamentally rational

beings. This led to the most important part of Kant's ethics, the formulation

of the categorical imperative, which is the criterion for whether a maxim is

good or bad. Simply put, this criterion amounts to a thought experiment: to

attempt to universalize the maxim (by imagining a world where all people

necessarily acted in this way in the relevant circumstances) and then see if

the maxim and its associated action would still be conceivable in such a world.

For instance, holding the maxim kill anyone who annoys you and applying it

universally would result in a world which would soon be devoid of people and

without anyone left to kill. Thus holding this maxim is irrational as it ends

up being impossible to hold it. Universalizing a maxim (statement) leads to it

being valid, or to one of two contradictions — a contradiction in conception

(where the maxim, when universalized, is no longer a viable means to the end)

or a contradiction in will (where the will of a person contradicts what the

universalization of the maxim implies).

The first type leads to a "perfect

duty", and the second leads to an "imperfect duty." Kant's

ethics focus then only on the maxim that underlies actions and judges these to

be good or bad solely on how they conform to reason. Kant showed that many of

our common sense views of what is good or bad conform to his system but denied

that any action performed for reasons other than rational actions can be good

(saving someone who is drowning simply out of a great pity for them is not a

morally good act). Kant also denied that the consequences of an act in any way

contribute to the moral worth of that act, his reasoning being (highly

simplified for brevity) that the physical world is outside our full control and

thus we cannot be held accountable for the events that occur in it.

Virtue ethics

Virtue ethics describes the character of a

moral agent as a driving force for ethical behavior, and is used to describe

the ethics of Socrates, Aristotle, and other early Greek philosophers. Socrates

(469 BC – 399 BC) was one of the first Greek philosophers to encourage both

scholars and the common citizen to turn their attention from the outside world

to the condition of humankind. In this view, knowledge having a bearing on

human life was placed highest, all other knowledge being secondary.

Self-knowledge was considered necessary for success and inherently an essential

good. A self-aware person will act completely within his capabilities to his

pinnacle, while an ignorant person will flounder and encounter difficulty. To

Socrates, a person must become aware of every fact (and its context) relevant

to his existence, if he wishes to attain self-knowledge. He posited that people

will naturally do what is good, if they know what is right. Evil or bad actions

are the result of ignorance. If a criminal was truly aware of the mental and

spiritual consequences of his actions, he would neither commit nor even

consider committing those actions. Any person who knows what is truly right

will automatically do it, according to Socrates. While he correlated knowledge

with virtue, he similarly equated virtue with happiness. The truly wise man

will know what is right, do what is good, and therefore be happy.

Philosophers have found ethical theories useful

because they help us decide why various actions are right and wrong. If it is

generally wrong to punch someone then it is wrong to kick them for the same

reason.

We can then generalize that it is wrong to

―harm‖ people to help understand why punching and kicking tend to both be

wrong, which helps us decide whether or not various other actions and

institutions are wrong, such as capital punishment, abortion, homosexuality,

atheism, and so forth. All of the ethical theories have various strengths and

it is possible that more than one of them is true (or at least accurate). Not

all moral theories are necessarily incompatible. Imagine that utilitarianism,

the categorical imperative, and Stoic virtue ethics are all true. In that case

true evaluative beliefs (e.g. human life is preferable) would tell us which

values to promote (e.g. human life), and we would be more likely to have an

emotional response that would motivate us to actually promote the value. We

would feel more satisfied about human life being promoted (e.g. through a cure

to cancer) and dissatisfied about human life being destroyed (e.g. through

war). Finally, what is right for one person would be right for everyone else in

a sufficiently similar situation because the same reasons will justify the same

actions.

Related Topics