Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Terrorism, Mass Casualty, and Disaster Nursing

Emergency Preparedness

EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS

Federal, State, and Local Responses

There are many resources

available at the federal, state and local levels to assist in the management of

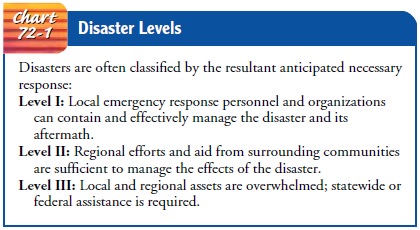

disasters and emergencies. Disasters are often assigned levels, which indicate

the anticipatedlevel of response (Chart 72-1). A list of the local resources

with specific instructions about how and when to contact them should be readily

available and frequently reviewed for needed updates. The following are a few

of the resources that may be of assistance during a mass casualty incident (MCI) or a disaster.

FEDERAL AGENCIES

There are many federal

resources that can be accessed through a process of requests. The state

authorities must request the feder-alization of resources through the proper

channels. This request for federal resources generally is made when local

resources have become or are in the process of becoming depleted.

Federal resources

include organizations such as Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS)

and the Department of Justice (DOJ). Each of these federal departments oversees

hundreds of agencies that may respond to MCIs. For example, the Federal Bureau

of Investigations (FBI) (under the DOJ) may be used for scene control and

collection of forensic evidence. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)

can acti-vate teams such as the Urban Search and Rescue Teams (USRTs). The DHSS

administers the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the

National Disaster Medical System (NDMS). The NDMS has many medical support

teams, such as Disaster Medical Assistance Teams (DMATs), Disaster Mortu-ary

Response Teams (DMORTs), Veterinary Medical Assistance Teams (VMATs), and

National Medical Response Teams for Weapons of Mass Destruction (NMRTs).

The DMAT provides medical personnel who can set up and

staff a field hospital; there are many DMATs located across the country. There

are only four NMRTs: the mobile California, North Carolina, and Colorado teams

and the Washington, DC team, which is stationary. These specialty teams were

developed to respond to situations involving WMDs. They consist of spe-cially

trained medical and technical personnel. The National Guard is also a resource,

with some guard units functioning as Civil Strike Teams (CSTs).

Also included in federal resources are the teams from the

CDC. This is the lead federal agency for disease prevention and control

activities and provides backup support to state and local health departments.

An additional support is available from the American Red Cross, which provides

many support systems and shelter as needed.

STATE AND LOCAL AGENCIES

Some of the state and local agencies may be the same agencies already listed (eg, local CDC and FBI agencies). Other state and local resources may include the American Red Cross, poison control centers, and other local volunteer organizations.

The Metro Medical Response Teams Systems (MMRS) are local teams that are

located in cities deemed to be possible terrorist targets and are funded for

specialty response to WMDs. Many state and federal task forces have been

developed to assist in the development and improvement of civilian medical

response to chemical and bio-logical terrorism.

Most cities and all

states have an Office of Emergency Man-agement (OEM). The OEM coordinates the

disaster relief efforts at the state and local levels. The OEM is responsible

for providing interagency coordination during an emergency. It maintains a

corps of emergency management personnel, including respon-ders, planners, and

administrative and support staff.

THE INCIDENT COMMAND SYSTEM

The Incident Command

System (ICS) is a management tool for organizing personnel, facilities,

equipment, and communication for any emergency situation. The federal

government mandates that the ICS be used during emergencies. Under this

structure, one person is designated as incident commander. This person must be

continuously informed of all activities and informed about any deviation from

the established plan (Currance & Bronstein, 1999; Lewis & Aghababian,

1996; Londorf, 1995). Whereas the ICS is primarily a field structure and process,

aspects of it are used at the level of an individual hospital’s emergency

response plan as well.

Hospital Emergency Preparedness Plans

Every facility is required by the Joint Commission on

Accredita-tion of Healthcare Organizations ( JCAHO) to create a plan for

emergency preparedness and to practice this plan twice a year (Burgess, Kirk,

Burron, & Cisek, 1999; JCAHO, 2000). Gener-ally these plans are developed

under the Environment of Care Committee or Safety Committee and are overseen by

an admin-istrative liaison.

Before the basic

emergency operations plan (EOP) can be de-veloped, the planning committee of

the facility first evaluates the community to anticipate the types of natural

and manmade dis-asters that might occur. This is not a difficult task and should

be a responsibility of the local facility, safety committee, safety of-ficer,

or emergency department (ED) manager. This information can be gathered by

questioning local law enforcement and fire de-partments and assessing the

amount of air or train traffic, auto-mobile traffic, and flood, earthquake,

tornado, or hurricane activity. Consideration is given to special situations

such as proximity to chemical plants, nuclear facilities, or military bases

that may en-hance the community’s potential for manmade disasters. Federal,

judicial, or financial buildings, schools, and any places where large groups of

people gather can be considered high-risk areas.The planning committee must

have a realistic understanding of its resources. It must determine, for example,

whether the fa-cility has a pharmaceutical stockpile available to treat

specific chemical or biological agents (Anteau, 1997; Stopford, 2000). Another

scenario that might be anticipated, the dispersal of a pul-monary intoxicant or

choking agent, requires that emergency op-erations planners find out how many

ventilators would be available in the facility and in the community. The

committee might also outline how staff would triage and assign priority to

patients when the number of ventilators is limited. Multiple fac-tors influence

a facility’s ability to respond effectively to a sudden influx of injured

patients, and the committee must anticipate var-ious scenarios to improve its

preparedness.

COMPONENTS OF EMERGENCY OPERATIONS PLAN

Once the initial assessment is complete, the facility

develops the

EOP. Essential components of the plan are as follows:

·

An

activation response: The EOP activation response of

ahealth care facility should define where, how, and when the response is

initiated.

·

An

internal/external communication plan: Communicationis critical

for all parties involved, including communication to and from the prehospital

arena (Heightman, 1999; Lewis & Aghababian, 1996; Mickelson, Burno, &

Schario, 1999).

·

A

plan for coordinated patient care: A response is planned

forcoordinated patient care into and out of the facility, in-cluding transfers

to other facilities. The site of the disaster can determine where the greater

number of patients may self-refer.

·

Security

plans: A coordinated security plan involving facilityand

community agencies is key to the control of an other-wise chaotic situation.

·

Identification

of external resources: External resources

areidentified, including local, state, and federal resources and information

about how to activate these resources.

·

A

plan for people management and traffic flow: “People man-agement”

includes strategies to manage the patients, the public, the media, and

personnel. Specific areas are assigned, and a designated person is delegated to

manage each of these areas (Anteau, 1997; Lewis & Aghababian, 1996).

·

A

data management strategy: A data management plan

forevery aspect of the disaster will save time at every step. A backup system

for charting, tracking, and staffing is devel-oped if the facility has a computer

system.

·

Deactivation

response: Deactivation of the response is as im-portant as

activation; resources should not be overused. The person who decides when the

facility is able to go from the disaster response back to daily activities is

clearly identified. Any possible residual effects of a disaster must be

considered before this decision is made (Anteau, 1997).

·

A

post-incident response: Often facilities see increased

volumesof patients up to 3 months after an incident. Post-incident response

must include a critique and a debriefing for all parties involved, immediately

and again at a later date.

·

A

plan for practice drills: Practice drills that include

com-munity participation allow for troubleshooting any issues before a

real-life incident occurs.

·

Anticipated

resources: Food and water must be available forstaff, families, and

others who may be at the facility for an extended period.

·

Mass

casualty incident planning: MCI planning includessuch

issues as mass fatality and morgue readiness.

·

An

educational plan for all of the above: A strong educationalplan

for all personnel regarding each step of the plan allows for improved readiness

and additional input for fine-tuning of the EOP (Howard, 2001; Kotzmann, 1999;

Anteau, 1997; Burgess et al., 1999; Lewis & Aghababian, 1996; Heightman,

2000; Levitin & Siegelson, 1996).

The EOP should also

include a structure that defines roles for all employees in each emergency

situation. The most common structure is the ICS described earlier, but applied

at the level of the hospital itself instead of at the site of the disaster. For

exam-ple, an administrator, possibly the nurse executive, will act as In-cident

Commander within the hospital and coordinate all aspects of the implementation

of the plan. Other personnel will be des-ignated to perform key roles, such as

resource manager or patient disposition coordinator. Such a predetermined

organization is es-sential to minimize confusion, ensure that all key

operations are directed, and promote a well-coordinated response.

Related Topics