Chapter: Essential Anesthesia From Science to Practice : Clinical management : General anesthesia

Early post-operative care - Anesthesia

Post-operative care

The

post-operative care of the patient can be divided into an early and a continued

phase. The early phase lasts from the moment the patient leaves the operating

room until he is discharged from the Post-Anesthesia Care Unit (PACU) or its

equi-valent. The care is then continued, a phase that can extend for days or even

weeks.

Early post-operative care

Based on

his medical condition and the planned operative procedure, we will have

classified the patient as ambulatory (also known as outpatient), as

‘post-operative admit’ (the patient comes to the hospital on the day of the

operation and is admitted to the hospital after his operation), or as an

inpatient (the patient is already in the hospital, or will be admitted for

pre-operative preparation, and will stay there post-operatively). Two

categories of patients might bypass the PACU (formerly called the Recovery

Room): (i) ambulatory patients who had a minor procedure and are expected to be

ready for discharge in a matter of minutes and (ii) patients requiring

intensive care because of serious pre-operative med-ical problems or major

operations with potential complications. Such patients are admitted directly to

the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) upon completion of the operation.

For patients coming to the PACU we consider

three factors: the patient’s pre-operative condition; the effects of the just

completed therapeutic (surgical, radio-logical, obstetrical, electroconvulsive)

or diagnostic procedure; and the effects of the anesthetic. As we turn the

patient’s care over to the PACU staff, we provide a formal “report” of his condition

including the following:

·

pre-existing medical conditions with particular emphasis on

pre-existing respiratory, cardiac, and chronic pain issues;

·

surgical disease, operative and anesthetic course, and any problems

encoun-tered;

·

fluid status including what was administered, estimated blood loss,

and urine output;

·

medications administered in the operating room. We mention

antagonists given to counteract lingering neuromuscular weakness or respiratory

depression or nausea and vomiting. Should the patient need more such

medication, the PACU physician can either continue the already initiated

treatment or, if the patient does not respond, switch to another drug;

·

concerns regarding the procedure or the patient, including the plan

for post-operative pain management;

·

issues requiring follow-up such as pending laboratory evaluations

or a chest radiograph to confirm central venous catheter placement.

Finally,

we make certain the patient is stable, record a first set of vital signs

obtained in the PACU, and ensure that all documentation is complete and

correct.

In the

PACU, we first worry about safety. We consider waning anesthetic drug effects

as they relate to adequacy of oxygenation, which in turn requires an alert

respiratory center (is there a hangover effect from CNS depressants?) and the

muscle power to breathe (is there a hangover effect from muscle relaxants or a

regional anesthetic?), an open airway (is there obstruction of the upper

airway?), and no encumbrance to breathing from dressing, position, or the

surgical proce-dure. Adequacy of oxygenation also requires adequate circulation

(is the blood pressure normal and the ECG unchanged from its preoperative

state?). The pulse oximeter will speak volumes to these questions. If the

patient is breathing roomair and his

oxygenation (as measured by pulse oximetry located peripherally) isnormal, we

can be assured of adequate breathing.

We

assess the central nervous system, recognizing that the patient usually will

have had a number of drugs with CNS effects. With modern anesthetic techniques

and drugs, we expect the patient to rally from the depressant effects of the

drugs fairly rapidly and to become responsive, if not immediately oriented. Up

to 25% of elderly patients will be delirious after a general anesthetic for a

major surgical procedure. Once a patient is not only responsive but also

oriented, we know that his brain is perfused and oxygenated.

Most

patients will arrive with an intravenous infusion. If we assume that the

patient is in a neutral fluid balance (blood pressure and urine output back to

preoperative values), in short, if his insensible losses (about 800 mL/day) and

intra-operative losses (from evaporation from exposed surfaces, e.g.,

intestines, bleeding and from edema caused by the surgical trauma (the

so-called third space or blister)) have been replaced, fluid therapy will

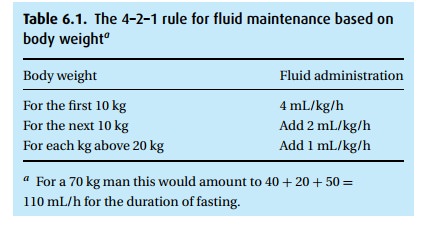

simply continue to replace insen-sible losses following the 4–2–1 rule (see

Table 6.1).

Often

enough, however, some bleeding continues – usually invisibly – into the traumatized

tissue. Fluid therapy will need to be adjusted to meet the patient’s

requirements as judged by cardiovascular signs and urine production. A

bal-anced salt solution such as normal saline or Ringer’s lactate will serve as

long as there is no need to worry about electrolytes, red blood cells, and

plasma proteins.

Early post-operative pain

As we

reassure ourselves as to the patient’s safety, we begin to consider the

patient’s pain. Three points need attention: (i) surgical incisional pain will

decrease over time, (ii) analgesic effects left over from the anesthetic will

wane over time, and (iii) pain counteracts the CNS depressant (respiratory)

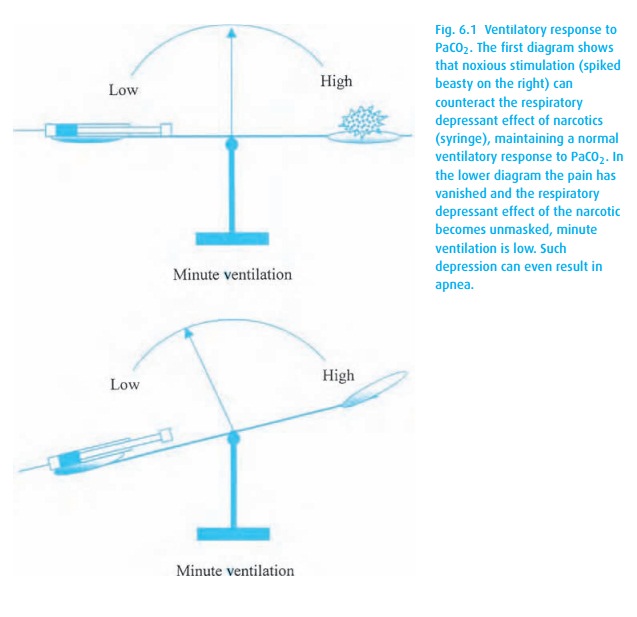

effects of narcotic analgesics (Fig. 6.1).

Thus, pain management in the PACU must seek a balance of three shifting slopes

of which we do not know the rate of change. This translates into: watch the patient and titrate drugs to

balance adequate analgesia and avoid respir-atory depression. As long as the

patient cannot take oral medication, a practical approach for the acute phase

of pain management in the PACU can make use of intravenous morphine in 2.0 mg

increments for the average adult. It takes about 5 minutes for such a dose to

show an effect. Therefore, wait at least 5 minutes before giving the next dose.

Many factors influence the patient’s response to such treatment. A patient on

chronic narcotic therapy will require more, a frail elderly person less.

Titrate! Titrate! Titrate!

After

minor surgical procedures, many patients will not require opioids at all, and

most can take oral medication. The pharmacology chapter gives drugs and

dosages.

There

would be no need for a PACU if it were not for the occasional complica-tions

that require early recognition and prompt treatment. Here is a quick review of

potential problems encountered in the PACU.

Complications

Desaturation

Differential diagnosis

·

Hypoventilation Always first assist ventilation

to establish normal SpO2 and PaCO2! Then consider causes and their treatment.

Residual neuromuscular blockadeSuspected when the patient shows anabnormal

respiratory pattern, particularly the tracheal tug, i.e., downward motion of

the larynx with inspiration. Test with the twitch monitor. Treat with reversal

agents.

– Residual sedationConsider reversal of benzodiazepines with

flumazenil.

– NarcosisTypically a slow, deep respiratory pattern;

consider cautious reversalof opioids with naloxone.

– Bronchospasm (wheezing)Intubation is a strong stimulant for

bronchospasm;treat with bronchodilators.

– Laryngospasm (stridor)If related to the operation, e.g., neck

operation withpossible hematoma formation, it becomes a surgical emergency. Try

continu-ous positive airway pressure, letting the patient exhale against

resistance (5 to 10 cmH2O) and maintaining that pressure throughout

the respiratory cycle.

– PainParticularly with a subcostal incision where

deep breathing is painful.

·

Ventilation/Perfusion mismatch

– AtelectasisProbably the most common cause of

post-operative hypoxemia.

– Aspiration of gastric

contentsParticularly

in high-risk patients, or if intubationrequired multiple attempts.

– PneumothoraxEspecially after central venous access. Obtain

a chest radio-graph, but be prepared to relieve the pneumothorax by puncture

(2nd inter-costal space, mid-clavicular line) should a tension pneumothorax

develop in the meantime.

– Pulmonary embolismThromboembolism is the most common. May needV/Q

or CT scanning. Most surgical patients require some form of prophylaxis against

deep vein thrombosis (DVT).

– Pneumonia

– Mainstem intubation

·

Diffusion block

– Pulmonary edema

·

Inadequate FiO2

Management

(i)Airway

Chin

lift, neck extension; continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) often helps.

For this, use a bag and mask system (Mapleson – see The anesthesia machine)

with a high flow (15 L/min) of oxygen. Apply the face mask tightly, letting the

patient exhale against resistance (5 to 10 cmH2O) and maintain that

pressure throughout the respiratory cycle.

(ii) Breathing

·

Supplemental oxygen

– Via nasal cannula, but with oxygen flows of 2 L/min the inspired O2only

increases by about 6%.

– Via

standard tent face mask for an inspired O2of up to 50%

– Via partial rebreathing face mask for an inspired O2of

up to 80%

– Via non-rebreathing face mask for an inspired O2of up to

95%

·

Encouragement – “take a breath!” often effective with narcotic

depression

·

Bag–Mask – use with self-inflating bag or Mapleson

·

Check ventilator settings, O2 supply and end-tidal CO2

if the patient is intubated.

(iii)

Studies to consider

·

Chest radiograph if abnormal breath sounds (pneumonia, atelectasis,

pneumothorax, +/− aspiration). Keep in mind, however, that a

portable film may not provide the highest quality and consolidation takes some

time to manifest radiographically.

·

Arterial blood gas

·

Twitch monitor if patient appears to be partially paralyzed.

Hypotension

Differential diagnosis

·

Inadequate preload

– Inadequate fluid resuscitation

– Continued hemorrhage

– Venodilation due to medications or sympathetic blockade

– Pericardial tamponade

– Pulmonary embolism

– Increased intra-abdominal pressure, e.g., big uterus pressing on

vena cava

– Increased intra-thoracic pressure, e.g., tension pneumothorax

·

Poor contractility

– Residual anesthetics

– Myocardial ischemia

– Fluid overload (“far-side” of the Starling Curve)

– Pre-existing cardiac dysfunction

– Electrolyte disturbance

– Hypothermia

·

Inadequate afterload

– Sepsis

– Vasodilation due to medications or sympathetic blockade, e.g.,

neuraxialanesthetic

– Anaphylaxis

·

Arrhythmias

– Bradycardia

– Loss of atrial kick

Atrial

fibrillation/flutter AV dissociation

– Electrolyte disturbance

Management

·

Physical examination (especially chest auscultation)

·

ECG (at least 5-lead strip) to detect arrhythmias and ischemia ACLS

protocol if abnormal rhythm

·

Hemoglobin level

·

Intravascular fluid resuscitation +/− blood transfusion Supplemental oxygen

·

Elevate legs to enhance venous return Consider transthoracic echo

·

Consider chest radiograph

·

Consider invasive monitoring

·

Check electrolytes, especially Ca2+ for inotropy and K+ , Mg2+ for arrhythmias

Hypertension

Differential diagnosis

·

Pain

·

Pre-existing hypertension Bladder distension

·

Rebound hypertension (especially with chronic clonidine) Endocrine

problem (thyroid storm, pheochromocytoma) Malignant hyperthermia

·

Delirium tremens

·

Increased intracranial pressure

Management

·

Treat pain or anxiety if present.

·

Review for pre-existing hypertension and reinstitute

anti-hypertensive therapy where appropriate.

·

Check ECG.

·

Look for additional signs of malignant hyperthermia.

·

Check for high bladder dome. If Foley catheter in place, check

patency, or per-form in-and-out catheterization.

We hope

that none of these problems arose or that they have been dealt with

successfully, at which point we are ready to discharge the patient from the

PACU.

PACU discharge

A

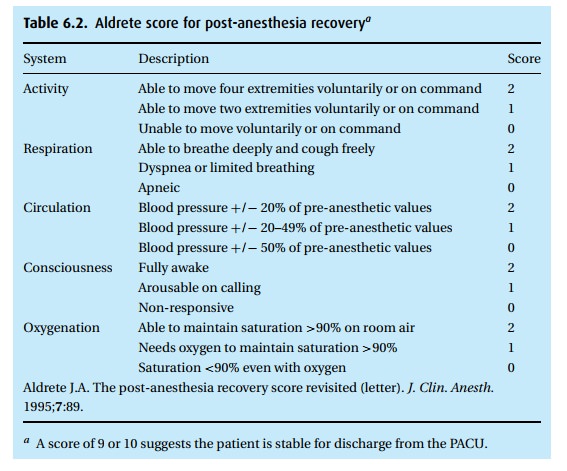

frequently used checklist is the Aldrete Recovery Score (see Table 6.2). If the sum of points reaches 9 or 10, we can

discharge the patient from the PACU.

Outpatients

After

outpatient procedures under local or peripheral nerve block anesthe-sia,

perhaps with parenterally administered CNS depressants, e.g., midazolam

(Versed®), propofol or opioids, the patient may bypass the PACU unless a

med-ical condition would call for observation. It may be necessary to prescribe

an oral analgesic that might include a mild opioid.

If no CNS depressant drug was used during the procedure and if the peripheral nerve block is behaving as expected (surgical anesthesia wearing off, but perhaps analgesia continuing), the patient can be discharged. We still insist that a relative or friend accompany them home because the patient will have been exposed to the stress of an operation – however minor – and will have been fasting and thus be at risk of swooning or even fainting and not being at the height of his reflex responses.

For

those patients who required CNS depressants for a short operative proce-dure in

which no severe post-operative pain is expected, e.g., a sigmoidoscopy under

propofol sedation or a cataract removal under local anesthesia preceded by a

small (0.5 to 0.75 mg/kg) dose of methohexital (Brevital®) to minimize the

discomfort of the retrobulbar block, the recovery process can be completed in a

matter of minutes to an hour, at which point the patient can be discharged into

the care of a relative or friend for transportation home. We always assume that

drug effects and hormonal disturbances will linger for a matter of several

hours to a day, so that upon discharge, the patient cannot be considered ready

to drive an automobile or ride a bicycle or even cross the street by himself.

For

those patients who remain in the hospital following their operation, PACU

discharge signals the phase of continued post-operative care.

Related Topics