Chapter: Essential Anesthesia From Science to Practice : Clinical management : General anesthesia

Continued post-operative care - Anesthesia

Continued post-operative care

The

patient will go through important changes in response to a major operation with

anesthesia. The stress of the inflicted surgical trauma will trigger a release

of adrenocorticotropic hormones, cortisol, and catecholamines. Catabolism will

overpower anabolism; the patient will be in a negative nitrogen balance.

Coagulation

changes might further thrombosis. Incisional pain and narcotic anal-gesics can

reduce pulmonary gas exchange. Narcotics inhibit the cough reflex, already

reduced in the elderly, causing patients to retain bronchial secretions, potentially

leading to atelectasis and pneumonitis. Large fluid loads given dur-ing the

operation need to be mobilized, yet antidiuretic hormone secretion will favor

water and salt retention. An ileus after intra-abdominal procedures often takes

days to resolve while nasogastric suction deflates the stomach not without

removing electrolytes. In short, many major operations will leave the patient

in a greatly debilitated state that can take several days to resolve.

If these

processes are superimposed on extensive surgical operations, for exam-ple those

affecting heart, lung or brain, the patient will be admitted to the ICU. This

will also be true for post-operative patients who come with pre-existing

disease processes involving the cardiovascular (congestive heart failure,

recent myocar-dial infarction), or respiratory (obstructive lung disease)

systems, the central ner-vous system (stroke, tumor), metabolism (diabetes),

hepatic or renal systems, or infection. The available frequency of observation,

extent of monitoring, and immediacy of care in the ICU does not match what is

available in the operating room, but greatly exceeds whatever can be offered on

the post-surgical ward.

When we

visit the patient on the post-surgical ward, we will not only consult his chart

to see the trends in vital signs (cardiovascular, respiratory and temperature)

but also assess fluid status and medications prescribed and given. We then talk

to the patient to gauge his mental status (up to 25% of elderly patients can

take up to a week to become fully oriented, and some 10% have cognitive

impairment lasting for months) and to ask about his comfort. We might have to

explain that hoarse-ness (from an endotracheal tube) or a sore throat (from an

LMA or endotracheal tube) are likely to improve in a day or two. We continue to

worry about pulmonary complications, e.g., atelectasis and pneumonitis, which

are most likely in elderly men, in smokers, and after operations that involve

the upper abdomen and the chest. Being aware that myocardial infarctions are

far more likely to occur – many of them silently – on the second post-operative

day than in the operating room, we pay special attention to the cardiovascular

system. Hypotension, hypertension (often pre-existing), and arrhythmias are not

uncommon.

Pain management

As

anesthesiologists, we are particularly attentive to the patient’s pain and its

management. We now use a widely employed standardized method of assessing pain

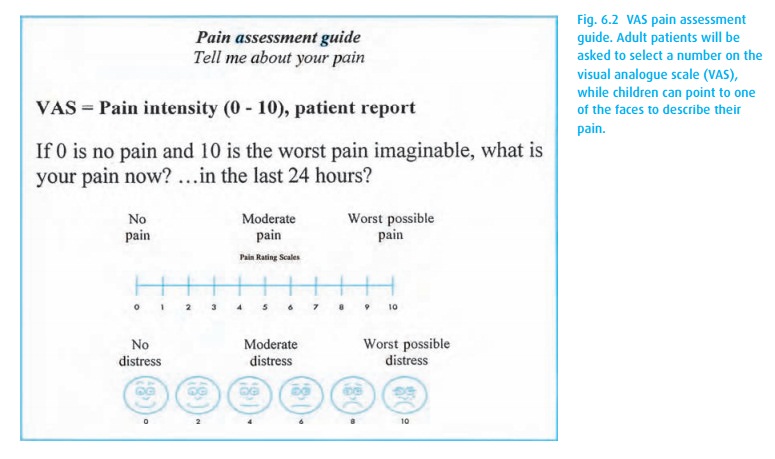

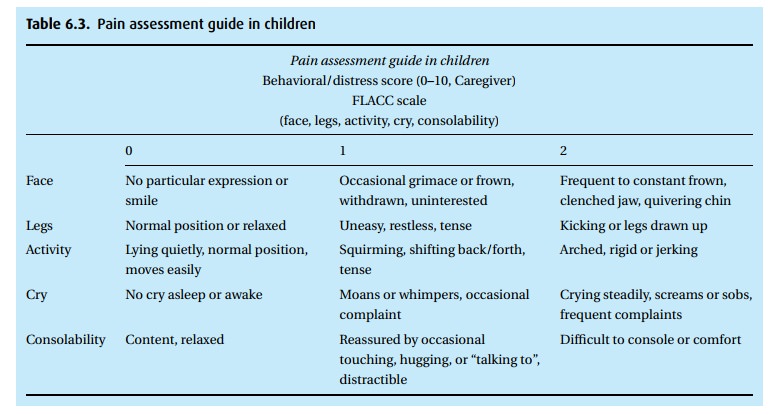

in adults and children (Fig. 6.2). In

children incapable of relating their pain, physical signs can help (Table 6.3). The treatment of pain will be influenced by

its severity.

If the patient is unable to take oral medication, we can institute patient-controlled intravenous opioid administration (PCA), a system that enables the patient to trigger an intravenous injection of a predetermined amount of a nar-cotic.

The PCA pumps can be programmed to deliver a specific volume, then to lock the

system for a predetermined period. When the patient pushes a button, a typical

program might deliver (into a running intravenous drip) a 1 mL bolus containing

1.0 mg morphine. The pump then goes into a lockout mode, making an additional

injection impossible for a preprogrammed period of, for example, 5 minutes. The

pump can be programmed to limit the hourly injection to, for example, no more

than 12 mg/h. Even that amount will be excessive if the patient were to

self-administer the maximum, hour after hour. The dose and the lock-out period

have to be tailored for the individual patient. While morphine is the

stan-dard, several drugs are available, among them hydromorphone (Dilaudid®)

and fentanyl. In addition, for patients who pre-operatively have become

tolerant to opioids, a background infusion of the narcotic may be required.

Depending

on the operation (some cause much more severe and protracted pain than others;

some limit oral intake for a longer period) and the patient (some are much more

sensitive than others), a PCA pump might be available to the patient for a day

or a week or more. Once narcotics are no longer needed, or the patient can

tolerate p.o. intake, oral medications take over. A great variety of drugs are

available (see Pharmacology).

Some

patients will still have an epidural catheter in place that had served the

anesthetic management during a thoracic, abdominal or lower extremity

oper-ation and can now be used for pain management. Typically, we infuse a low

concentration of local anesthetic combined with a narcotic through the

catheter. By combining these drugs, we minimize the amount of motor block

(paralysis) from the local anesthetic while limiting narcotic side effects

(nausea, itching, and urinary retention) associated with larger doses of

opioids. Once we establish a level of analgesia with a bolus injection, an

infusion is begun and the patient might regulate the administration of

additional drug with a PCA pump (PCEA: patient controlled epidural analgesia).

Dose and concentration of local anes-thetic and lock-out period will have to be

adjusted for the individual patient and drugs infused. A typical arrangement

might deliver 0.2 mg of morphine in 1.0 mL fluid containing 0.25% bupivacaine

and a lock-out period of 10 minutes. Other approaches use a continuous epidural

infusion alone.

The

post-operative recovery will progress slowly. Every day, if all is going well,

we can see improvements. Indeed, we can often see the moment when the patient

‘turns the corner’ from negative to positive nitrogen balance. He will start

shaving, she will do her hair and even put on lipstick. The patient will begin

to eat, and we can switch from parenteral to oral medication. Many patients

will be discharged from the hospital with prescriptions for oral analgesics.

See the Pharmacology chapter for a list of commonly used drugs, dosages and

duration of effect.

Related Topics