Chapter: Biochemical Pharmacology : Pharmacodynamics

Drug dose-effect relationships in biochemical cascades

Drug dose-effect relationships in biochemical cascades

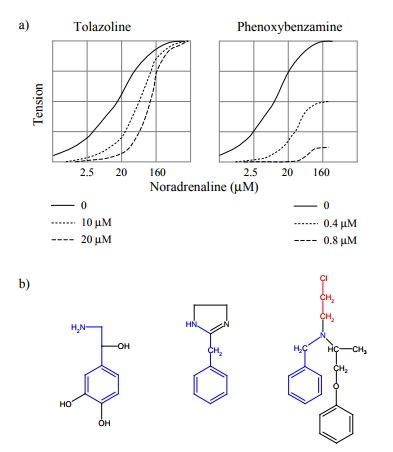

We noted the

similarity of empirical dose-effect relationships with theoretical plots

(Figures 3.5a, 3.3, 3.4). This needs to be qualified in two ways:

1. While the theoretical plots modeled receptor

saturation, the experiment measured muscle tension.

2. This similarity is by no means perfect.

The two statements are in

fact related. In our example, a perfect similarity of theoretical and

experimental plots could only be expected if there were a linear relationship

between receptor saturation with norepinephrine and mus-cle contraction. Considering

that muscle contraction is trig-gered quite a bit downstream of receptor

activation, there are numerous possible factors that will `distort' this

lineari-ty, and in reality no linear relationship will ever be observed if drug

target and drug effect are separated by intervening biochemical cascades. It

thus turns out that the shape of a dose-effect relationship will depend very

much on the func-tional proximity of the drug receptor molecule and the

ob-served parameter.

If we can directly observe

the function of the receptor, which thus at the same time is the effector,

there will indeed be a linear relationship between the receptor interaction of

a drug and its effect on function, respectively. As examples, we could name:

• Enzymes – observed function: enzyme catalysis;

• Ion channels – observed function: ion

conductivity.

On the other hand, very often

the observed effect is mea-sured a long way downstream of the drug receptor, as

in our example of smoth muscle contraction and α-adrenergic blockers. Other such examples are

• The inhibition of cyclooxygenase by

acetylsalicylic acid, which results in a decrease in prostaglandin syn-thesis,

with perceived pain relief as the functional read-out;

• The activation or inhibition of nuclear hormone

recep-tors by synthetic androgens, with a readout (way) down-stream of

transcriptional regulation such as muscle growth or inhibition of sperm

production (a highly edu-cational example, isn't it).

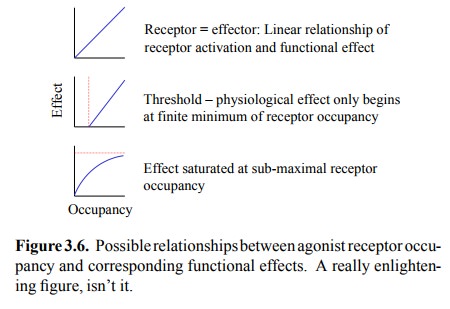

In cases like these, there

will be numerous possible reasons for deviations from linearity in the

dose-effect relationship. The deviations from linearity may of course take any

shape; two typical effects are illustrated in Figure 3.6.

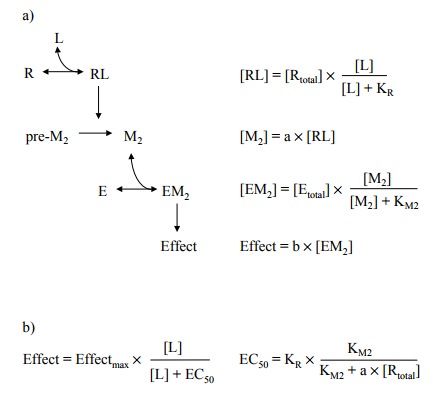

A hormone receptor typically

triggers a biochemical cas-cade with multiple steps that need to occur before a

func-tional effect is accomplished. This indirect coupling has surprising

consequences for the relationship between the saturation of the receptor and

that of the functional effect. We will consider the effect of cascading

mediators in a very simple model6, containing the following

assumptions (Fig-ure 3.7a):

1. The primary agonist (L) binds to the receptor

(R) accord-ing to the law of mass action.

2. The ligand-bound receptor promotes the

formation of a second messenger (M2), so that the concentration of M2 is at all

times proportional to the receptor occupancy, with a as their ratio. (This condition would be fulfilled if the rate of

M2's formation were proportional to [RL], and M2's decay

a first order process.)

3. The second messenger (M2) saturably

binds to the effec-tor, and the observed effect is proportional to the extent

of effector saturation with M2.

From these fairly

straightforward assumptions, the relation-ships summarized in Figure 3.7b and

3.7c can be derived.

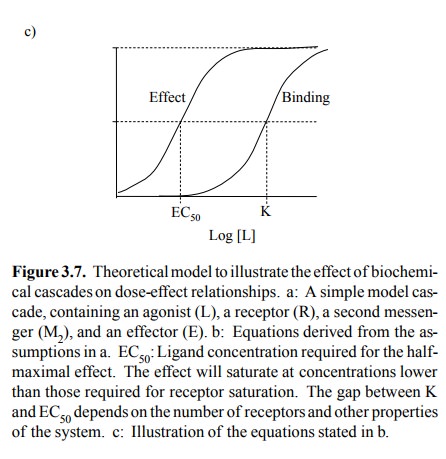

You can see that the relation

between effect ligand concen-tration has the same shape as receptor occupancy.

Howev er, the EC50 – meaning the ligand concentration required for

50% of the maximum effect – is rather smaller than K R, the

equilibrium constant of receptor binding. Thus, sim-ply because receptor and

effector are indirectly connected by means of a second messenger, the

functional response of the system saturates at ligand concentrations that may

be substantially lower than those required for saturating the receptor.

Importantly, the gap between EC50 and KR will widen with

increasing numbers of receptors. Thus, an in-crease in the number of receptors

will always increase the sensitivity of the overall cascade to the ligand, even

if all the components downstream of the receptor remain the same.

As an example of this effect,

we may consider the stimula-tion of the heart by epinephrine, which acts on β-adrener-gic receptors. Half-maximal increase of heart muscle

con-tractility (i.e., EC50) is observed at 2% receptor saturation.

Interestingly, β-receptors are subject to regulation by both

covalent modification (phosphorylation) and reversible removal from the cell

surface. Either process would re-duce the sensitivity of the system to

epinephrine but leave the maximum response observed at receptor saturation

unchanged.

Related Topics