Chapter: Essential Microbiology: Protista

Diatoms - Structural characteristics of algal protists

Diatoms

The diatoms, which belong to the division Chrysophyta

(the golden-brown algae), make up the majority of phytoplankton in marine food

chains, and as such are the most important group of algal protists in terms of

photosynthetic production. Over 10 000 species of diatom are recognised, but

some experts feel that the real number is many times greater than this.

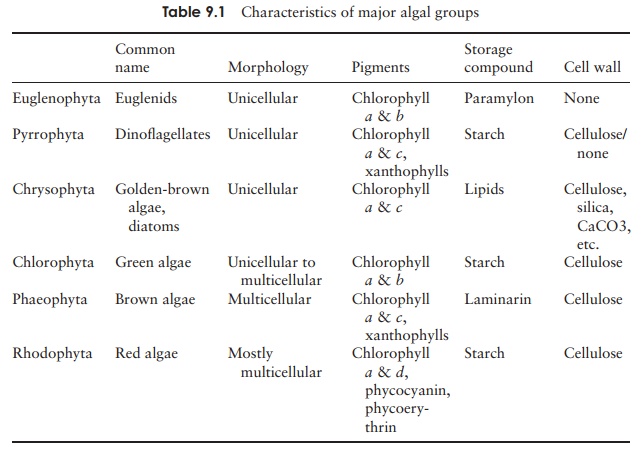

As with the dinoflagellates, chlorophylls a and c are present, but not chlorophyll b. Their colour is due to carotenoids and xanthophylls

(particularly fucoxanthin) masking the chlorophyll.

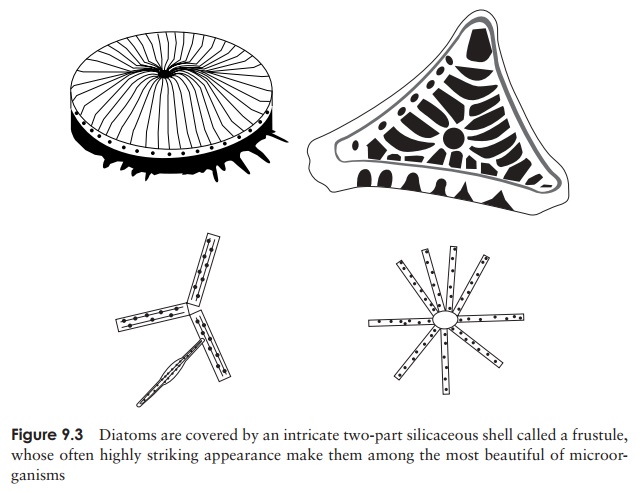

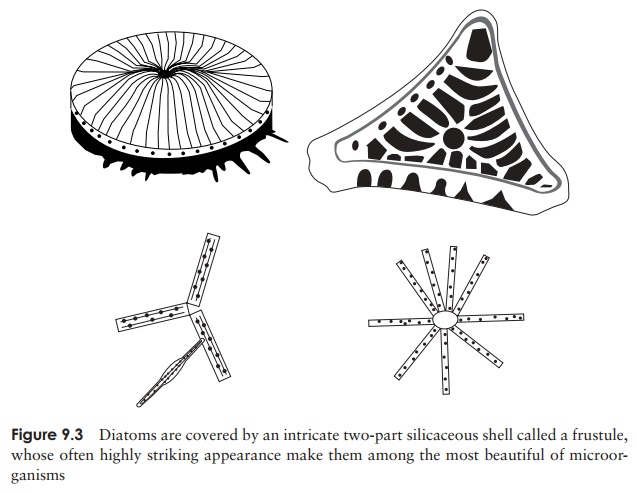

Diatoms have their cells surrounded by a silica-based

shell known as a frustule, composed

of two overlapping halves (the epitheca and the hypotheca). Microbiologists are

rarely able to resist the temptation to liken this structure to that of a petri

dish, and with good reason. With the electron microscope it can be seen that

the frustule is perforated with numerous tiny pores that connect the protoplast

of the cell with the outside environment. Diatom classification is based almost

entirely on the shape and pattern of these shells, which are uniform for a particular

species, and often have a very striking appearance (Figure 9.3). When diatoms

die, their shells fall to the bottom of the sea, and can accumulate in thick

layers where they represent a valuable mineral resource. This fine, light

material (diatomaceous earth) has a number of applications, for example in

filtration systems, and also as a light abrasive in products such as silver

polish or toothpaste.

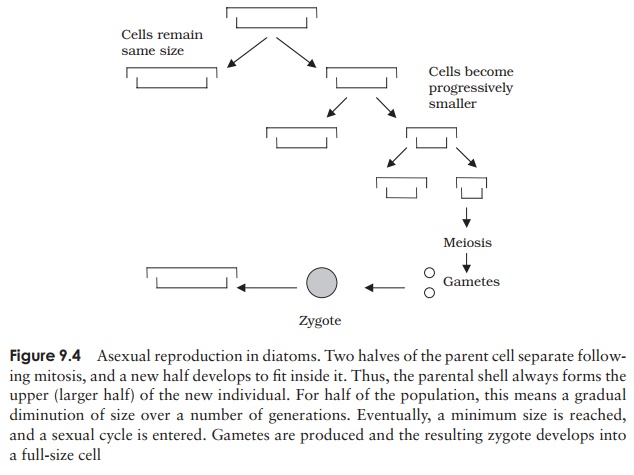

Reproduction is usually asexual by binary fission,

but a sexual phase with the produc-tion of haploid gametes can occur.

Chrysophytes are unusual among the three primitive groups of algae in that they

are diploid. In diatoms, asexual reproduction involves mi-totic cell division,

with each daughter cell receiving one half of the parental frustule, and synthesizing

a new one to complement it. The newly formed half, however, always acts as the

hypotheca (lower half) of the new cell; consequently, one in two daughter cells

will be slightly smaller than the parent, an effect which is heightened over a

number

of generations (Figure 9.4). This process continues

until a critical size is reached, and the diatoms undergo a phase of sexual

reproduction, which re-establishes the normal frustule size. In species whose

frustules have a degree of elasticity, the daughter cells are able to expand,

and the problem of cell diminution does not arise. In bilaterally sym-metrical

(long, thin) diatoms, meiosis in parental cells produces identical, non-motile

gametes, which fuse to form a zygote. The radially symmetrical (round) forms

provide an example of the third pattern of gamete fusion found in the algae: oogamy. Here, there is a clear

distinction between the small, motile sperm cell and the larger, immobile egg

cell. Both are produced by meiosis in the parental cell, followed, in the case

of the male, by several rounds of mitosis, to give a large number of sperm

cells.

Related Topics