Chapter: Medical Microbiology: An Introduction to Infectious Diseases: Dermatophytes, Sporothrix, and Other Superficial and Subcutaneous Fungi

Dermatophyte Disease

DERMATOPHYTE DISEASE

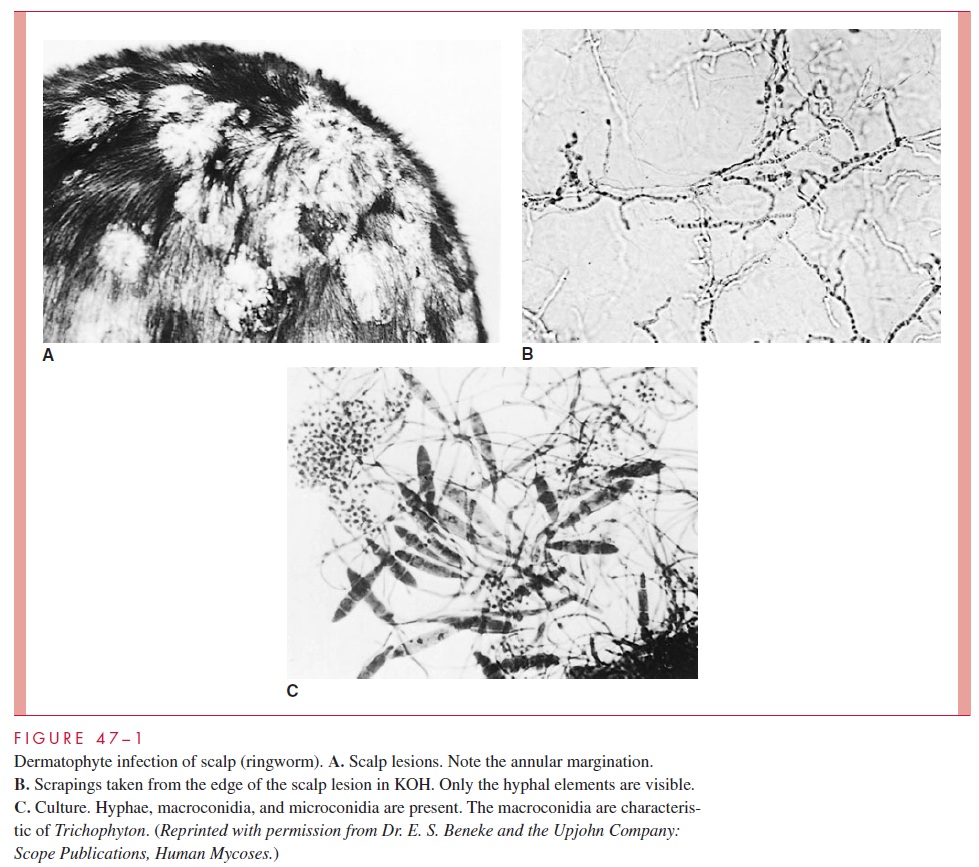

Dermatophytoses are slowly progressive eruptions of the skin and its appendages which may be unsightly but are not painful or life threatening. The manifestations (and names) vary depending on the nature of the inflammatory response in the skin, but typically involve erythema, induration, itching, and scaling. The most fa-miliar is “ringworm,” which gets its name from the annular shape of creeping margin at the advancing edge of dermatophyte growth.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

There are both ecologic and geographic differences in the occurrence of the various der-matophyte species. Some are primarily adapted to the skin of humans, others to animals, and others to the environment. All may serve as the source for human infection. Many wild and domestic animals, including dogs and cats, are infected with certain dermatophyte species and represent a large reservoir for infection of humans. There are large differences between temperate and tropical climates in the frequency of cases and isola-tions from nonhuman sources of the different species. Many of these differences are changing with shifts in population.

Human-to-human transmission usually requires close contact with an infected subject or infected person or animal, because dermatophytes are of low infectivity and virulence. Transmission usually takes place within families or in situations involving contact with de-tached skin or hair, such as barber shops and locker rooms. No special precautions beyond handwashing need be taken by the medical attendant after contact with an infected patient.

PATHOGENESIS

Dermatophytoses begin when minor traumatic skin lesions come in contact with dermato-phyte hyphae shed from another infection. Susceptibility may be enhanced by local fac-tors such as the composition surface fatty acids. Once the stratum corneum is penetrated, the organism can proliferate in the keratinized layers of the skin aided by a variety of pro-teinases. The course of the infection is dependent on the anatomic location, moisture, the dynamics of skin growth and desquamation, the speed and extent of the inflammatory re-sponse, and the infecting species. For example, if the organisms grow very slowly in the stratum corneum, and turnover by desquamation of this layer is not retarded, the infection will probably be short-lived and cause minimal signs and symptoms. Inflammation tends to increase skin growth and desquamation rates and helps limit infection, whereas im-munosuppressive agents such as corticosteroids decrease shedding of the keratinized lay-ers and tend to prolong infection. Invasion of any deeper structures is extremely rare.

Most infections are self-limiting, but those in which fungal growth rates and desqua-mation are balanced and in which the inflammatory response is poor tend to become chronic. The lateral spread of infection and its associated inflammation produce the char-acteristic sharp advancing margins that were once believed to be the burrows of worms. This characteristic is the origin of the common name ringworm and the Latin term tinea (worm) that is often applied to the clinical forms of the disease (Fig 47–1A).

Infection may spread from skin to other keratinized structures, such as hair and nails, or may invade them primarily. The hair shaft is penetrated by hyphae, which extend as arthroconidia either exclusively within the shaft (endothrix) or both within and outside the shaft (ectothrix). The end result is damage to the hair shaft structure, which often breaks off. Loss of hair at the root and plugging of the hair follicle with fungal elements may result. Invasion of the nail bed causes a hyperkeratotic reaction, which dislodges or distorts the nail.

IMMUNITY

The great majority of dermatophyte infections pass through an inflammatory stage to spontaneous healing. Phagocytes are able to use oxidative pathways to kill the fungi both intracellularly and extracellularly. Little is known about the factors that mediate the host response in these self-limiting infections or whether they confer immunity to subse-quent exposures. Antibodies may be formed during infection but play no known role in im-munity. Most clinical and experimental evidence points to the importance of cell-mediated immunity (CMI), as with other fungal infections. The timing of the inflammatory re-sponse to infection correlates with appearance of delayed hypersensitivity, and resolution of infection is associated with the blastogenic T-lymphocyte responses. Enhanced desqua-mation with the inflammatory response helps remove infected skin.

Occasionally, dermatophyte infections become chronic and widespread. This progres-sion has been related to both host and organism factors. Approximately half of these pa-tients have underlying diseases affecting their immune responses or are receiving treatments that compromise T-lymphocyte function. These chronic infections are particularly associ-ated with Trichophyton rubrum, to which both normal and immunocompromised persons appear to be hyporesponsive. Although a number of mechanisms have been proposed, how this organism is able to grow without stimulating much inflammation is unexplained.

Related Topics