Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Mood Disorders: Depression

Depression: Pharmacotherapy and Other Somatic Treatment

Pharmacotherapy and Other Somatic Treatment

Treatment during the acute phase with medication is highly effi-cacious

in reducing signs and symptoms of MDD. Antidepressant medication has the most

specific effect on reduction of symptoms and is often associated with improved

psychosocial functioning. When symptoms of depression are mild to moderate, a course

of depression-specific psychotherapy without medicine may also be effective. If

symptoms of depression are moderate to severe, acute phase treatment with

medications is often indicated. A wide variety of antidepressant medications

have been documented as effective in moderate to severe MDD.

The range of treatments available in the USA has included the tricyclic

antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), heterocyclic

antidepressants and SSRIs. In addition, antidepressants with both serotonergic

and noradrenergic ac-tivity or noradrenergic activity alone have become

available. Clearly, clinical trials comparing the efficacy of newer treatments

with standard tricyclic antidepressants have shown equal efficacy with

improvement in overall tolerance to side effects with newer treatments.

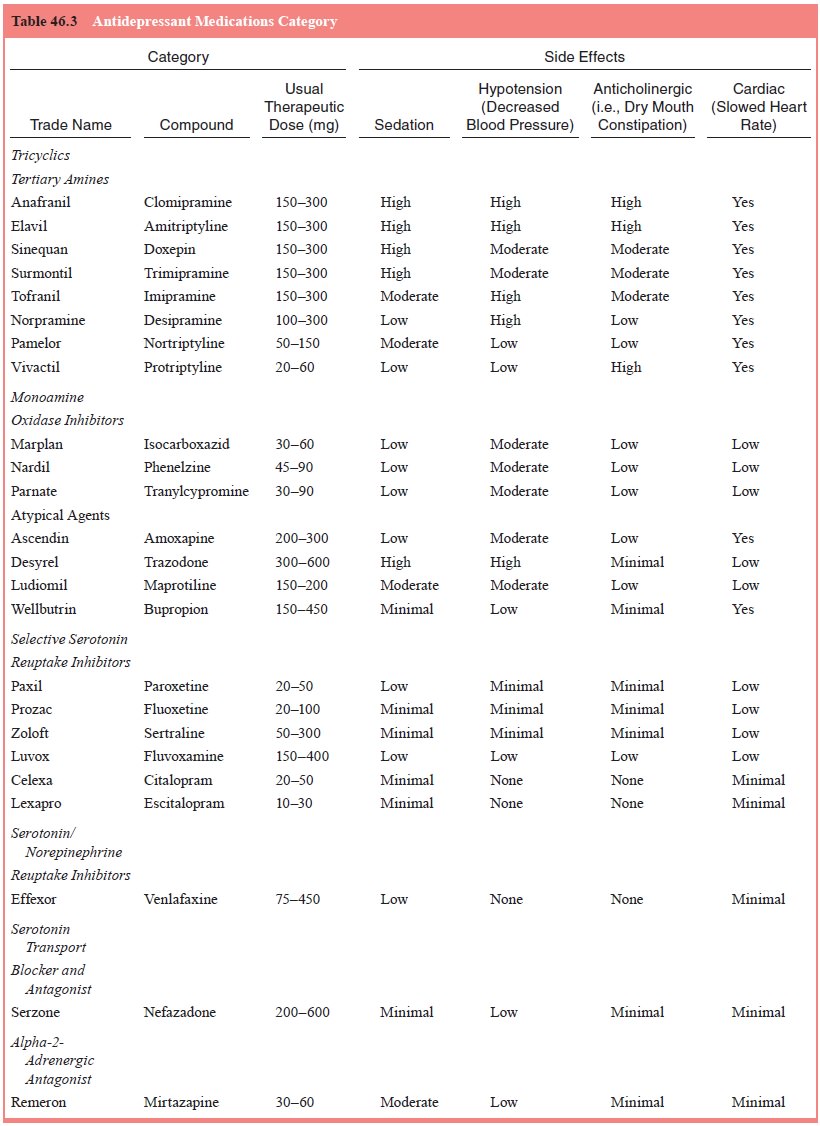

Antidepressant medications which are currently available for acute

treatment of MDD are listed in the associated table (Table 46.3).

Choice of treatment with a specific antidepressant treat-ment in a given

clinical situation is based on prior treatment response to medication,

consideration of potential side effects, history of response in first-degree

relatives to medicines, and the associated presence of cooccurring psychiatric

disorders that may lead to a more specific choice of antidepressant treat-ment.

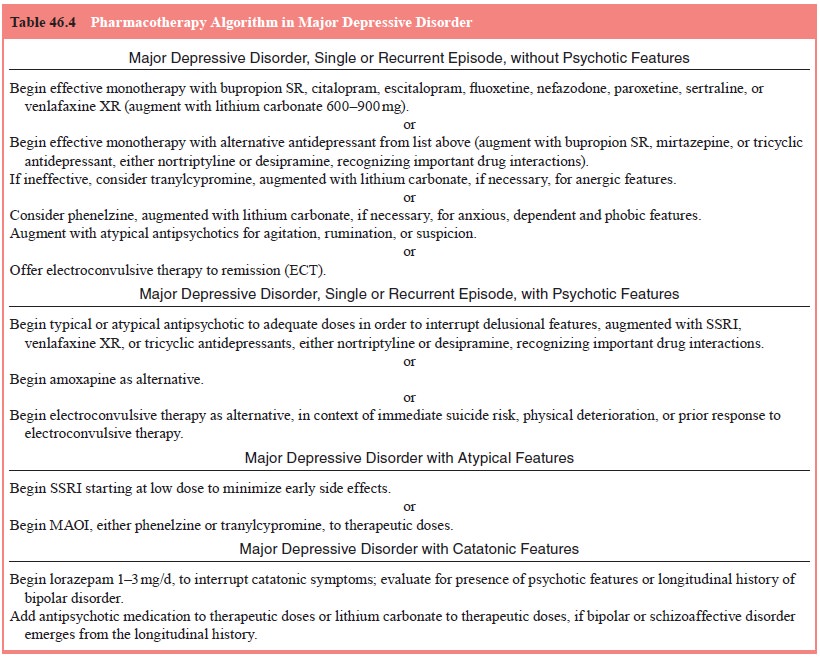

Table 46.4 illustrates an algorithm developed for pharma-cotherapy of MDD which

includes a staged trial of newer medi-cations (because of their superior

side-effect profiles) followed by treatments with older medicines available for

the treatment of MDD. The ultimate goal of pharmacotherapy is complete

remission of symptoms during a standard 6- to 12-week course of treatment.

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors

The most commonly prescribed antidepressant medicines in the past 10

years are SSRIs. They are selectively active at se-rotonergic neurochemical

pathways and are effective in mild to moderate nonbipolar depression. They may

also be particularly effective in MDD with atypical features as well as DD.

Often these treatments are well tolerated and involve single daily dos-ing for

MDD. Because of selective serotonergic activity, these treatments have also

been demonstrated to be effective with cooccurring OCD, panic disorder,

generalized anxiety disorder, PTSD, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, bulimia

nervosa, so-cial anxiety disorder, as well as MDD. They tend to be reason-ably

well tolerated in individuals with comorbid medical con-ditions. There are

particular medication-specific interactions based on inhibition of cytochrome

P-450 liver enzyme systems which require attention if an individual is taking

other medica-tions for primary medical conditions or associated psychiatric

conditions. The currently available SSRIs in the USA include fluoxetine,

paroxetine, sertraline, fluvoxamine, citalopram and escitalopram.

Other Newer Antidepressants

In addition to SSRIs, greater attention has been brought to medi-cines with dual noradrenergic and serotonergic pathways includ-ing venlafaxine which has become available in both immediate release (IR) and extended release formulations. In addition, an alpha-2-adrenergic agonist, mirtazapine has become available, as well as a serotonin transport blocker and antagonist nefazodone. Recent concerns about hepatic complications associated with nefazodone has required liver function monitoring. A predomi-nantly noradrenergic and dopaminergic agonist, bupropion is also available in an immediate release and sustained release (SR) preparation. The newest dual acting antidepressant marketed in the USA is duloxetine.

Tricyclic Antidepressants in Individuals with Severe MDD Including Melancholic Features

Tricyclic antidepressants have been best studied in individuals with MDD

with melancholic features and with psychotic fea-tures. The combination of

typical antipsychotic pharmacother-apy in association with tricyclic

antidepressants has been rec-ommended. The side-effect profile of tricyclic

antidepressants has included moderate to severe sedation, anticholinergic

effects including constipation and cardiac effects which has made these

medicines less popular in typical primary care or psychiatric practice.

Nevertheless, the secondary amines which are metabo-lites of imipramine and

amitriptyline, specifically desipramine and nortriptyline, have continued to be

useful agents in more re-fractory depression.

Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors

There continues to be a role for the use of MAOIs in patients with MDD

with atypical features. These agents particularly may be useful in intervention

in depressive episodes with atypical features, characterized by prominent mood

reactivity, reverse neurovegetative symptom patterns (i.e., overeating and

over-sleeping) and marked interpersonal rejection sensitivity. MAOIs continue

to have a significant role in treatment of comorbid panic disorder, social

phobia and agoraphobia if individuals are not responsive to SSRIs. The ongoing

prescription of phenelzine or tranylcypromine requires continued education of

the patient regarding standard food interactions involving tyramine as well as

specific drug–drug interactions involving sympathomimetic medications. These

cautions regarding diet and drug interaction makes MAO inhibitors less

attractive to primary care physicians and most psychiatrists. However, they

continue to be effective treatments which may be useful in depression with

atypical fea-tures as well as anergic bipolar depression.

Therapeutic Blood Levels

Although therapeutic blood level monitoring in the treatment of MDD may

have a role in future treatments, the only group of medicines where there has

been reliable assessment of blood lev-els are the tricyclic antidepressants.

Because tricyclic antidepres-sants have significant drug–drug interactions with

certain SSRIs there continues to be a need for therapeutic blood monitoring

particularly with nortriptyline and desipramine.

General Pharmacotherapy Recommendations

Increasingly, a trial of one class of antidepressants may be associ-ated

with incomplete response leading to a question of augment-ing a treatment with

another medicine versus switching from one medicine to another within the same

class or to a different class altogether. Augmentation strategies with other

medications, in-cluding adding lithium carbonate and other antidepressants,

particularly those with a different mechanism of action, atypical

antipsychotics, thyroid and stimulants, have been the focus of a number of

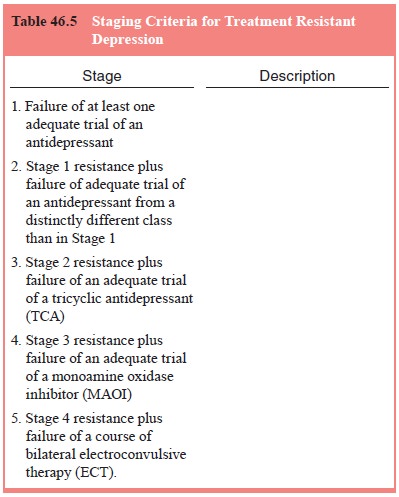

reviews of treatment resistance. A staging system for treatment resistant

depression (TRD) has been proposed and ranges from failure to respond to a

single agent (Stage 1) to failure of multiple treatments and electroconvulsive

therapy (Stage 5) as shown in Table 46.5.

Clinical Management

All of the antidepressant medications used in the treatment of MDD must

be prescribed in the context of an overall clinical

psychiatric relationship characterized by supportive interaction with

the patient and family and ongoing education about the nature of the disorder

and its treatment. Clinical management optimally involves careful monitoring of

symptoms using stand-ardized instruments and careful attention to side effects

of medi-cation in order to promote treatment adherence. Outpatient visits,

which may be scheduled weekly at the outset of treatment, and subsequently

biweekly encouragement and sustain collaborative treatment relationships. These

office consultations allow the psy-chiatrist to make dosage adjustments as

indicated, monitor side effects and measure clinical response to treatment.

For the majority of individuals with MDD, a course of 6 to 8 weeks of

acute treatment with weekly outpatient visits is indicated. Subsequent office

visits may be scheduled every 2 to 4 weeks during the continuation phase of

treatment. Appropri-ate adjustments of dose are determined by the psychiatrist

as indicated by best clinical judgments of medication effect. The dose of an

SSRI may be adjusted every 3 days on the basis of telephone contact and

follow-up visits may be scheduled every 7 to 10 days. Similarly, the adjustment

of dosing of tricyclic anti-depressants and MAOIs must be attended to carefully

in the first 2 to 3 weeks of treatment. Optimal dosing ranges of SSRIs,

tri-cyclics and MAOIs are noted in Table 46.3. Because of the early anxiety,

agitation and occasional insomnia associated with SS-RIs, somewhat lower doses

may be initiated early in the course before achieving the typical standard

therapeutic dose.

Incomplete response, which entails the failure to respond to acute

treatment with an antidepressant medication at 6 to 8 weeks, requires

reassessment of diagnosis and determination of adequacy of dosing. Ongoing

substance abuse, associated general medical condition or concurrent psychiatric

disorder may partially explain a lack of complete response. If substance

dependence is present, a full substance-free interval (preferablyweeks or

longer) with appropriate detoxification and rehabilita-tion may be indicated.

If a reassessment discloses an associated psychiatric disorder, then more

specific treatment of that associ-ated disorder, whether it be bipolar disorder

or concurrent post traumatic disorder, is necessary. If the reassessment

suggests an associated comorbid personality disorder, then appropriate and more

specialized psychotherapy may be necessary in order to achieve a complete

response to treatment. As indicated before, if the MDD has psychotic features,

then antipsychotic pharma-cotherapy to adequate doses must be initiated prior

to initiating a course of standard tricyclic antidepressants or a combined

se-rotonin norepinephrine uptake inhibitor such as venlafaxine. If MDD is

associated with severe personality disorder (e.g., bor-derline personality

disorder), then adjunctive psychotherapy and low dose antipsychotic medications

may be necessary. If the pa-tient has severe melancholic, delusional, or

catatonic features, a course of electroconvulsive therapy may be necessary to

achieve remission of symptoms.

There is also evidence that continuation of treatment be-yond 6 to 12

weeks may convert some partial responders to re-sponders if drug treatment is

increased to full doses. This time allows for evaluation of the role of focused

psychotherapy to ad-dress residual interpersonal disputes, loss or grief, or

ongoing social deficits. The associated augmentation strategies to stand-ard

treatments include lithium carbonate augmentation, tricyclic antidepressant

augmentation of SSRIs, thyroid hormone aug-mentation and bupropion augmentation

of SSRIs.

Electroconvulsive Therapy

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) remains an effective treat-ment in

patients with severe MDD and those individuals with psychotic MDD. Many

patients who have responded to electro-convulsive therapy do not respond to

pharmacotherapy. There is increased need for understanding the role of

maintenance electroconvulsive therapy in those individuals who respond to

electroconvulsive therapy because ongoing pharmacotherapy does not always

prevent recurrence of depression after ECT is successful. ECT can be

particularly useful in interrupting acute suicidality for those patients who

may require rapid resolution of symptoms. ECT may be indicated in older adults

when lack of self-care and weight loss may represent a greater risk. The most

common side effect associated with electroconvulsive therapy is amnesia for the

period of treatment. There is no consistent evidence to suggest chronic

cognitive or memory impairment as a result of ECT.

Other Somatic Treatments

Light therapy investigators have continued to demonstrate ben-efit in

individuals with seasonal MDD by providing greater than 2500 lux light therapy

for 1 to 2 hours/day. Many of these patients experience recurrent winter

depression in the context of a recur-rent MDD or bipolar II disorder. Bright

light exposure has been associated with favorable response within 4 to 7 days.

As with electroconvulsive therapy, light therapy is best prescribed by

specialists who have experience in its use and can appropriately evaluate the

indication for light therapy and monitor carefully the response to treatment.

Ongoing investigation of alternative brain stimulation techniques have

been the subject of recent investigation. The use of a powerful magnet to

provide transcranial magnetic stimula-tion has been the subject of several open

trials. It is not yet deter-mined whether the repetitive transcranial magnetic

stimulation demonstrates its effectiveness through reduction of inhibitory

neurotransmission or other mechanisms.

In addition, open clinical trials of vagus nerve stimula-tion (VNS)

which has been found to be effective in epilepsy has been the subject of

attention in refractory MDD. Several sites of investigation have begun to

reveal positive effects at 9 months using VNS implantation. This procedure

requires the implan-tation of a stimulating device in the chest with the

capacity to stimulate the vagus nerve at regular intervals through the course

of the day.

Related Topics