Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Mood Disorders: Depression

Comorbidity Depression Patterns: General Medical Conditions

Comorbidity Patterns: General Medical Conditions

Whereas a 4 to 5% current prevalence rate of MDD exists in community

samples, symptoms of depression are found in 12 to 36% of patients with a

general medical condition (Depression Guideline Panel, 1993). The rate of

depression may be higher in patients with a specific medical condition. MDD is

identified as an independent condition and calls for specific treatment when it

occurs in the presence of a general medical condition.

The Depression Guideline Panel includes four possible relationships

between depression and a general medical condi-tion: 1) depression is

biologically caused by the general medical condition; 2) an individual who

carries a genetic vulnerability to MDD manifests the onset of depression

triggered by the gen-eral medical condition; 3) depression is psychologically

caused by the general medical condition; and 4) no causal relationship exists

between the general medical condition and mood disor-der. The first two cases

warrant initial treatment directed at the general medical disorder. Treatment

is advocated for persistent depression upon stabilization of the general

medical condition. When the general medical condition causes depression,

specific treatment for the former condition is optimized, while psychi-atric

management, education and antidepressant medication are administered to treat

the depression. In cases where the two con-ditions are not etiologically

related, appropriate treatment is indi-cated for each disorder.

Stroke

Some poststroke patients manifest depression due to cerebrovas-cular

disease related to cerebral infarction in left frontal and left subcortical

brain regions. Mood disorder due to cerebrovascular disease is diagnosed when

an individual manifests a recent stroke and has significant symptoms of

depression. A point prevalence of mood disorder due to cerebrovascular disease

in poststroke patients between 10 and 27% has been documented, with an av-erage

duration of depression lasting approximately 1 year. Case reports of mood

disorder due to cerebrovascular disease in post-stroke patients suggest poor

treatment compliance, irritability and personality change (Ross and Rush,

1981).

Dementia

According to DSM-IV-TR, when symptoms of clinically signifi-cant

depressed mood accompany dementia of the Alzheimer’s Type and, in the

clinician’s judgment, the depression is due to the direct physiological effects

of the Alzheimer’s disease, mood dis-order due to Alzheimer’s disease is

diagnosed. When dementia consistent with cerebrovascular disease leads to

prominent cog-nitive deficits, focal neurological signs and symptoms,

signifi-cant impairment in functioning as well as predominant depressed mood,

vascular dementia with depressed mood is diagnosed. The distinction between

depressive disorders and dementing disor-ders is often complicated because depression

and dementia com-monly cooccur. Treatment of cooccurring depressive features

may relieve symptoms and improve overall quality of life.

Parkinson’s Disease

Fifty percent of patients with Parkinson’s disease experience a MDD

during the course of the illness. When depression occurs in this context, one

diagnoses mood disorder due to Parkinson’s disease. Active treatment of the

depressive disorder may result in improvement in the signs and symptoms of

depression with-out alleviation of the involuntary movement disorder or

cognitivechanges associated with subcortical brain disease. The underly-ing

etiology of associated dementia and depressive disorder in Parkinson’s disease

appears to involve physiologic changes in subcortical brain regions.

Diabetes

It is estimated that the prevalence of depression in treated pa-tients

with diabetes is three times as frequent as in the general population. Further,

there is no difference in the prevalence rate of depression in patients with

insulin-dependent diabetes melli-tus (Type I) in comparison to patients with

noninsulin-dependent mellitus (Type II). The symptomatic presentation of MDD in

pa-tients with diabetes is similar to patients without diabetes. Con-sequently,

full assessment of and treatment for MDD is recom-mended in patients who become

depressed during the course of diabetes. The relatively high point prevalence

rate may be due to higher detection rate in this treated population, having a

chronic illness, as well as metabolic and endocrine factors.

Coronary Artery Disease

When MDD is present, increased morbidity and mortality is reported in

postmyocardial infarction patients as well as in pa-tients having coronary

artery disease without myocardial in-farction (MI). Therefore, treatment of MDD

in patients with coronary artery disease is indicated. Prevalence estimates of

MDD in postmyocardial infarction range from 40 to 65%. Over a 15-month period,

patients 55 years or older who had mood disorder evidenced a mortality rate

four times higher than expected, and coronary heart disease or stroke accounted

for 63% of the deaths. Depression may promote poor adherence to cardiac

rehabilitation and worse outcome. During the first year following MI,

depression is considered to be associated with a three- to fourfold increase in

subsequent cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Depression in patients with

coronary artery disease is associated with more social problems, func-tional

impairment and increased health care utilization. Recent studies of erectile

dysfunction, cardiovascular disease and de-pression demonstrate that all three

conditions share many of the same risk factors.

Cancer

MDD occurs in 25% of patients with cancer at some time during the

illness. MDD should be assessed and treated as an independ-ent disorder. The

intense reaction in patients diagnosed with cancer may lead to dysphoria and

sadness without evolving a full syndrome of MDD. The consulting psychiatrist

must evalu-ate the patient’s response to chemotherapy, side effects of the

treatment, and medication interactions in the overall assessment of the

patient. Among patients with cancer, MDD is typically characterized by

heightened distress, impaired functioning and decreased capacity to adhere to

treatment. Treating comorbid MDD with psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy may

improve the overall outcome in patients with cancer and mitigate complica-tions

of MDD.

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

Lifetime rates of MDD in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome range

from 46 to 75%. Comorbid anxiety and somatization dis-orders are also common in

patients with chronic fatigue. Ac-cording to the Centers for Disease Control

(CDC) criteria, the diagnosis of chronic fatigue syndrome is excluded in

patients whose symptoms meet criteria for a formal psychiatric disorder. such

as MDD or DD. Patients whose symptoms meet criteria for both a mood disorder

and chronic fatigue syndrome should be maximally treated for the mood disorder

with appropriate phar-macotherapy and cognitive–behavioral psychotherapy. The

etio-logical relationship between mood disorder and chronic fatigue syndrome is

unclear.

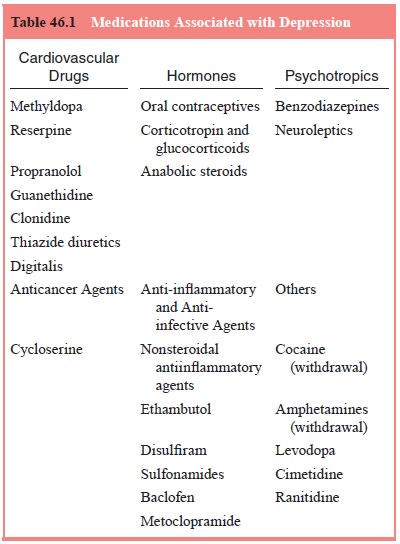

Depression Due to Medications

If MDD is judged to be a direct physiologic effect of a medica-tion,

then substance induced mood disorder is diagnosed. Medi-cations reported to cause

depression involve several drugs from the associated groups listed in Table

46.1.

Among antihypertensive treatment, beta-adrenergic blockers have been

studied regarding the risk of depression. No significant differences are found

between individuals treated with beta-blockers and those treated with other

antihyperten-sives regarding the propensity to develop depressive symp-toms.

Lethargy is the most common side effect reported. No significant depressive

complications are reported with calcium channel blockers or angiotensin

converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors.

Hormonal treatments, such as corticosteroids and ana-bolic steroids, can

elicit depression, mania, or psychosis. Oral contraceptives require monitoring

regarding the possible pre-cipitation of depressive symptoms. Because patients

with seizure disorders and Parkinson’s disease are at high risk for concomitant

MDD, it is difficult to establish a link between anticonvulsant or

antiParkinsonian treatment and the precipitation of depression. Nevertheless,

patients require close monitoring and evaluation for evolution of depressive

symptomatology

Related Topics