Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Substance Abuse: Sedative, Hypnotic, or Anxiolytic Use Disorders

Course and Natural History - Disorders of Sedative–Hypnotics

Course and Natural History

Once a diagnosis of sedative–hypnotic dependence is

manifested it is unlikely that a patient will be able to return to controlled,

therapeutic use of sedative–hypnotics. All sedative–hypnotics, including

alcohol, are cross-tolerant, and physical dependenceand tolerance are quickly

re-established if a patient resumes use of sedative–hypnotics.

If after sedative–hypnotic withdrawal the patient

has an-other primarily psychiatric disorder, such as generalized anxiety

disorder (GAD), panic attacks, or insomnia, alternate treatment strategies

other than sedative–hypnotics should be used if pos-sible. Definitive diagnosis

of a psychiatric disorder during early abstinence is often not possible because

protracted withdrawal symptoms may mimic anxiety disorders, and disruption of

sleep architecture for days to months after drug withdrawal is ex-tremely

common.

If the sedative–hypnotic dependence has developed

sec-ondary to stimulant or alcohol use, primary treatment of the chemical

dependence should be a priority. Often the symptom that was driving the

sedative–hypnotic use disappears after the patient is drug abstinent.

Detoxification

Three general strategies are used for withdrawing

patients from sedative–hypnotics, including benzodiazepines. The first is to

use decreasing doses of the agent of dependence. The second is to substitute

phenobarbital or some other long-acting barbiturate for the addicting agent,

and gradually withdraw the substitute medication. The third, used for patients

with a dependence on both alcohol and a benzodiazepine, is to substitute a

long-acting benzodiazepine, such as chlordiazepoxide, and taper it during 1 to

2 weeks.

The pharmacological rationale for phenobarbital substitu-tion is that phenobarbital is long-acting and little change in blood levels of phenobarbital occurs between doses. This allows the safe use of a progressively smaller daily dose. Phenobarbital is safer than the shorter-acting barbiturates; lethal doses of pheno-barbital are many times higher than toxic doses, and the signs of toxicity (e.g., sustained nystagmus, slurred speech and ataxia) are easy to observe. Finally, phenobarbital intoxication usually does not produce euphoria or behavioral disinhibition, so most patients view it as a medication, not as a drug of abuse.

The withdrawal strategy selected depends on the

particular benzodiazepine, the involvement of other drugs of dependence, and

the clinical setting in which the detoxification program takes place. The

gradual reduction of the benzodiazepine of depend-ence is used primarily in

medical settings for dependence arising from treatment of an underlying condition.

The patient must be cooperative, must be able to adhere to dosing regimens, and

must not be abusing alcohol or other drugs.

Substitution of phenobarbital can also be used to

withdraw patients who have lost control of their benzodiazepine use or who are

polydrug-dependent. Phenobarbital substitution has the broadest use for all

sedative–hypnotic drug dependencies and is widely used in drug treatment

programs.

Stabilization Phase

The patient’s history of drug use during the month

before treat-ment is used to compute the stabilization dose of phenobarbital.

Although many addicts exaggerate the number of pills they are taking, the

patient’s history is the best guide to initiating phar-macotherapy for

withdrawal. Patients who have overstated the amount of drug that they have

taken will become intoxicated during the first day or two of treatment.

Intoxication is easily managed by omitting one or more doses of phenobarbital

and re-ducing the daily dose.

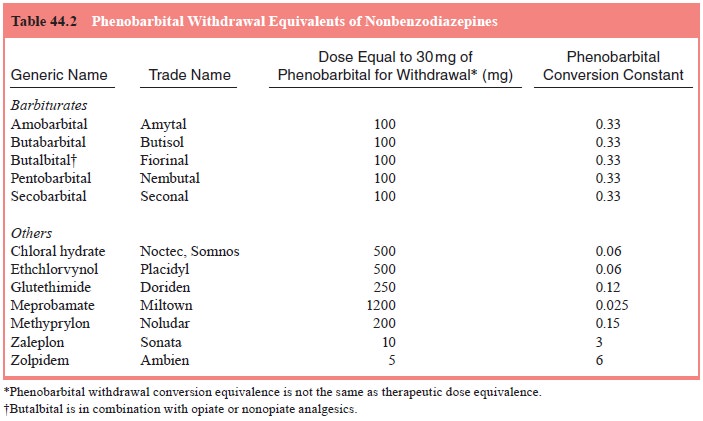

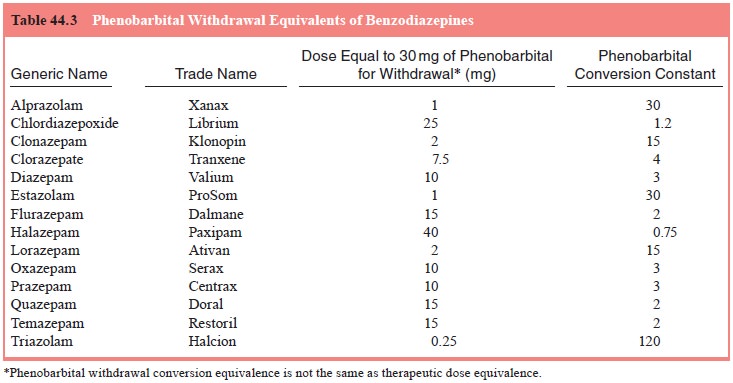

To compute the initial daily starting dose of phenobarbi-tal,

the patient’s average daily use of each sedative–hypnotic is estimated. Next,

the patient’s average daily sedative–hypnotic dose for each drug is converted

to its phenobarbital withdrawal equivalent by multiplying the average daily

dose by the drug’s phenobarbital conversion constant shown in either Table 44.2

or 44.3. Finally, the phenobarbital withdrawal equivalences for each drug are

added together. In any case, the maximum daily pheno-barbital dose is limited

to 500 mg/day. The total daily amount of phenobarbital is divided into three

doses per day.

Before receiving each dose of phenobarbital, the

patient is checked for signs of phenobarbital toxicity: sustained nystag-mus,

slurred speech, or ataxia. Of these, sustained nystagmus is

the most reliable. If nystagmus is present, the

scheduled dose of phenobarbital is withheld. If all three signs are present the

next two doses of phenobarbital are withheld, and the daily dosage of

phenobarbital for the next day is halved.

If the patient is in acute withdrawal and has had,

or is in danger of having withdrawal seizures, the initial dose of

pheno-barbital is administered by intramuscular injection. If nystagmus and

other signs of intoxication develop after 1 to 2 hours after the intramuscular

dose, the patient is in no immediate danger from barbiturate withdrawal.

Patients are maintained with the initial dosing schedule of phenobarbital for 2

days. If the patient has nei-ther signs of withdrawal nor phenobarbital

toxicity (slurred speech, nystagmus, unsteady gait) phenobarbital withdrawal is

begun.

Withdrawal Phase

Unless the patient develops signs and symptoms of

phenobarbi-tal toxicity or sedative–hypnotic withdrawal, phenobarbital is

decreased by 30 mg/day. Should signs of phenobarbital toxicity develop during

withdrawal, the daily phenobarbital dose is de-creased by 50% and the 30 mg/day

withdrawal is continued from the reduced phenobarbital dose. Should the patient

have objec-tive signs of sedative–hypnotic withdrawal, the daily dose is

in-creased by 50% and the patient is restabilized before continuing the

withdrawal.

Related Topics