Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Substance Abuse: Sedative, Hypnotic, or Anxiolytic Use Disorders

Additional Treatment Considerations - Disorders of Sedative–Hypnotics

Additional Treatment

Considerations

Psychiatric Comorbidity

Most patients who are being prescribed long-term benzodiazepine therapy have underlying major depressive disorder, panic disorder or GAD. The clinical dilemma is deciding which patients are receiving appropriate maintenance therapy for a chronic psy-chiatric condition. Physical dependence on benzodiazepines may be acceptable if the patient’s disabling anxiety symptoms are ameliorated. The reason for the patient’s request for benzo-diazepine withdrawal from long-term, stable dosing should be carefully explored. Valid reasons to discontinue benzodiazepine treatment include: 1) breakthrough of symptoms that were previously well controlled; 2) impairment of memory or other neurocognitive functions; and 3) abuse of alcohol, cocaine, or other medications.

Patients with severe underlying psychiatric

disorders may have unrealistic hopes of becoming medication-free. Often the

origin of request for benzodiazepine withdrawal comes from concerned friends or

relatives.

Abuse Potential of Benzodiazepines

Most people do not like the subjective effects of

benzodiazepines, especially in high doses. Even among drug addicts, the

benzodi-azepines alone are not common intoxicants. They are, however, widely

used by drug addicts to self-medicate opiate withdrawal and to alleviate the

side effects of cocaine and amphetamines. Patients receiving methadone

maintenance use benzodiazepines to boost (enhance) the effects of methadone.

Some alcoholic patients use benzodiazepines either in combination with alcohol

or as a second-choice intoxicant, if alcohol is unavailable. Fat-soluble

benzodiazepines that enter the CNS quickly are usually the benzodiazepines

preferred by addicts.

Addicts whose urine is being monitored for

benzodi-azepines prefer benzodiazepines with high milligram potency, such as

alprazolam or clonazepam. These benzodiazepines are excreted in urine in such

small amounts that they are of-ten not detected in drug screens, particularly

with thin-layer chromatography.

Treatment of High-dose Benzodiazepine Dependence

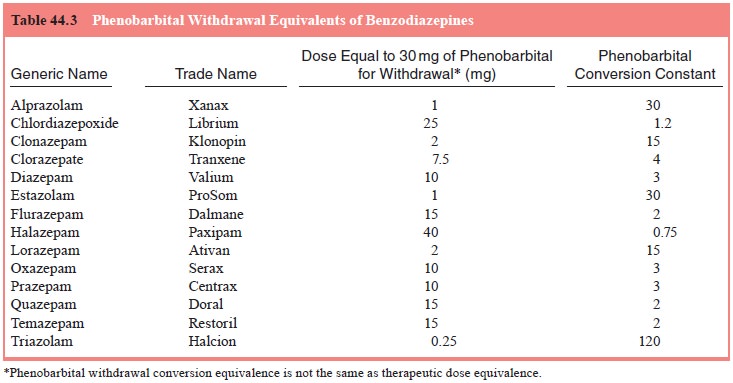

For high-dose benzodiazepine dependence, the

pharmacologi-cal treatment strategy is the same as that for barbiturates. The

phenobarbital conversion equivalents are shown in Table 44.3. The dose

conversions computed using Table 44.3 prevent the emergence of severe

withdrawal of the classic sedative–hypnotic types. Some patients who take high

doses of benzodiazepines, or even therapeutic doses for months to years, may

have prolonged withdrawal symptoms.

Low-dose Benzodiazepine Withdrawal Syndromes

Many people who have taken benzodiazepines in

therapeutic doses for months to years can abruptly discontinue the drug

with-out developing withdrawal symptoms. But other patients, taking similar

amounts of a benzodiazepine develop symptoms ranging from mild to severe when

the benzodiapine is stopped or when the dosage is substantially reduced.

Characteristically, patients toler-ate a gradual tapering of the benzodiazepine

until they are at 10 to 20% of their peak dose. Further reductions in

benzodiazepine dose then cause patients to become increasingly symptomatic. In

addition medicine literature, the low-dose withdrawal may be called

therapeutic-dose withdrawal, normal-dose withdrawal, or benzodiazepine

discontinuation syndrome. The symptoms can ultimately be categorized as symptom

reemergence, symptom rebound, or a prolonged withdrawal syndrome.

Many patients experience a transient increase in

symptoms for 1 to 2 weeks after benzodiazepine withdrawal. The symptoms are an

intensified return of the symptoms for which the benzodiazepine was prescribed.

This transient form of symptoms intensification is called symptom rebound. The term comes from sleep research in which

rebound insomnia is commonly observed after sedative–hypnotic use. Symptom

rebound lasts a few days to weeks after discontinuation Symptom rebound is the

most common withdrawal consequence of prolonged benzodiazepine use.

The symptoms for which the benzodiazepine has been

taken may return to the same level as before benzodiazepine therapy. This is

called symptom reemergence (or recrudescence). In other words, the patient’s

symptoms, such as anxiety, insom-nia, or muscle tension, that had abated during

benzodiazepine treatment return.

The reason for making a distinction between symptom

re-bound and symptom reemergence is that symptom reemergence suggests that the

original symptoms are still present and must be treated. Symptom rebound is a

transient withdrawal syndrome that will disappear over time.

A few patients experience a severe, protracted withdrawal

syndrome that includes symptoms (e.g., paresthesia and psycho-sis) that were

not present before. This withdrawal syndrome has generated much of the concern

about the long-term safety of the benzodiazepine

Related Topics